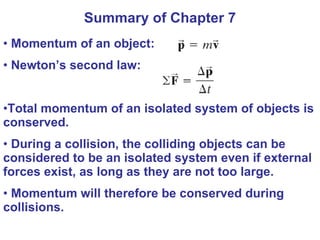

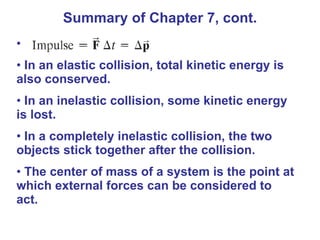

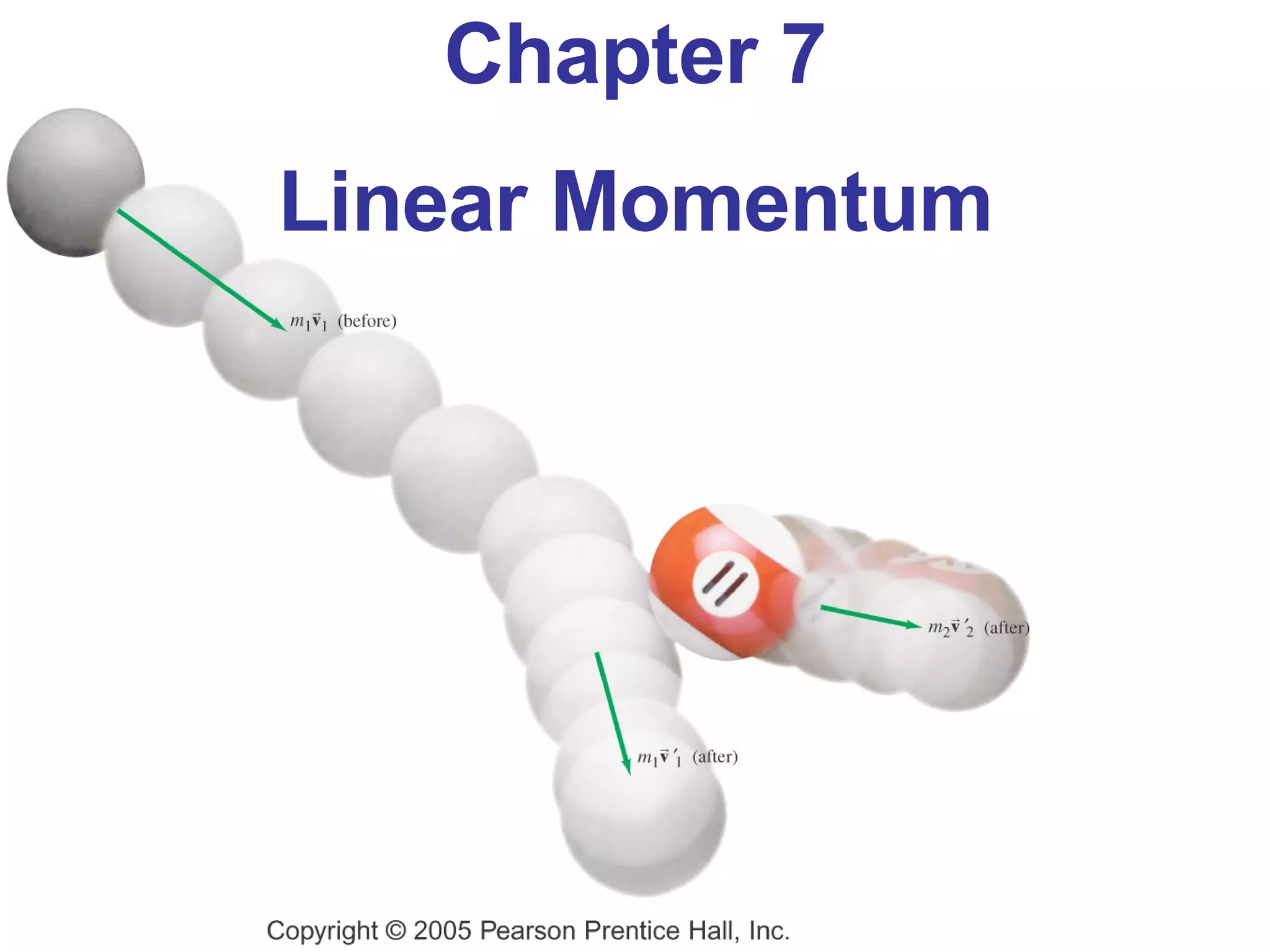

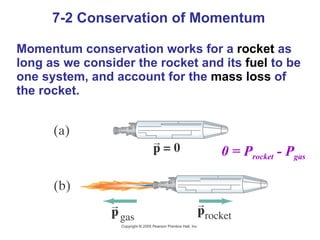

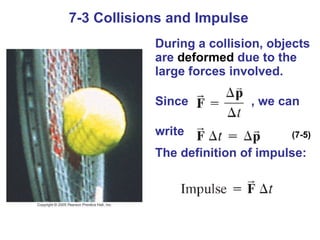

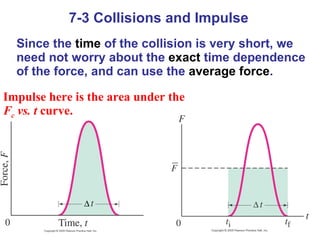

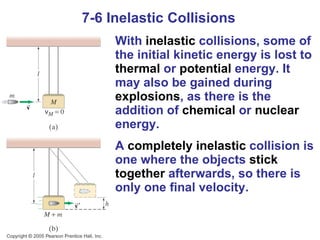

1. Chapter 7 discusses linear momentum and its relationship to force, conservation of momentum during collisions, and the conservation of energy and momentum in elastic and inelastic collisions.

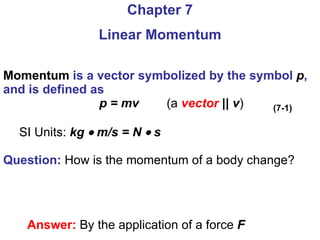

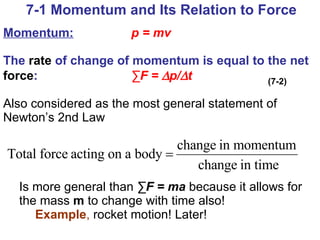

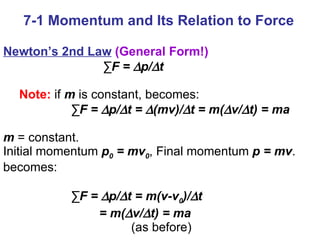

2. Momentum is defined as mass times velocity (p=mv) and changes due to an applied net force according to Newton's Second Law (Δp/Δt=F).

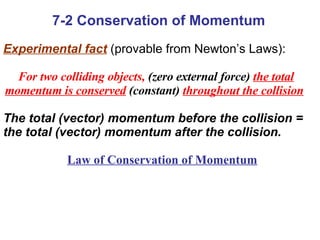

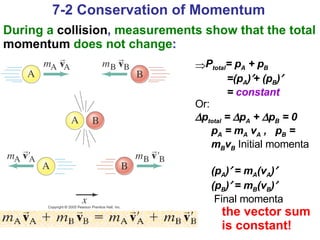

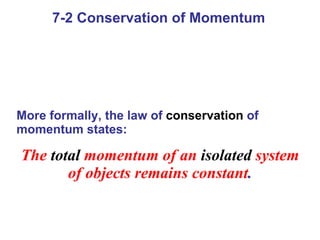

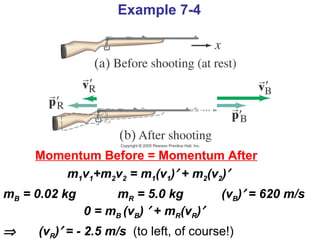

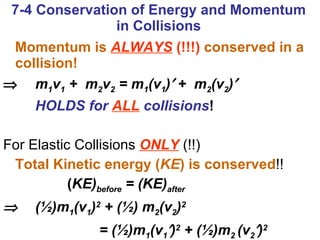

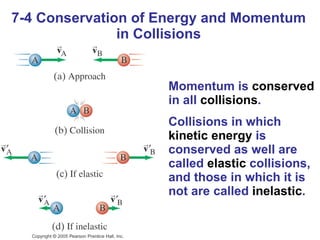

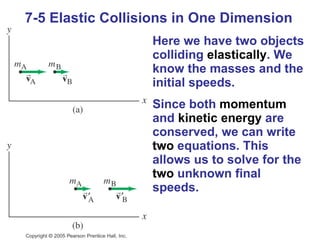

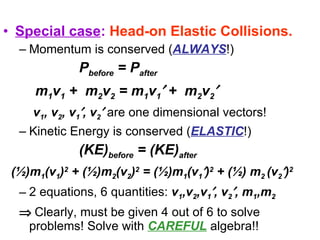

3. During collisions, the total momentum of an isolated system remains constant due to the conservation of momentum, which can be used to analyze collisions.

![∑ F = p/ t Initial p = mv Final p = 0 Water rate = 1.5 kg/s p = 0 – mv F = ( p/ t) = [(0-mv)/ t] = - mv/ t m = 1.5 kg every second On the water F = -30 N On the car F = 30 N Example 7-2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ppa6lecturech07-1217366224981674-9/85/Lecture-Ch-07-6-320.jpg)

![Collision: m 1 v 1 +m 2 v 2 = m 1 (v 1 ) + m 2 (v 2 ) Proof, using Newton’s Laws: Force on 1, due to 2, F 12 = p 1 / t = m 1 [(v 1 ) - v 1 ]/ t Force on 2, due to 1, F 21 = p 2 / t = m 2 [(v 2 ) - v 2 ]/ t Newton’s 3 rd Law : F 21 = - F 12 - m 1 [(v 1 ) - v 1 ]/ t = m 2 [(v 2 ) - v 2 ]/ t OR: m 1 v 1 +m 2 v 2 = m 1 (v 1 ) + m 2 (v 2 ) Proven ! A ->1 B->2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ppa6lecturech07-1217366224981674-9/85/Lecture-Ch-07-9-320.jpg)

![m 1 v 1 +m 2 v 2 = (m 1 + m 2 )V v 2 = 0, (v 1 ) = (v 2 ) = V V = [(m 1 v 1 )/(m 1 + m 2 )] = 12 m/s Example 7-3 Initial Momentum = Final Momentum (1D)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ppa6lecturech07-1217366224981674-9/85/Lecture-Ch-07-11-320.jpg)

![Impulse: m = 0.060 kg v = 25 m/s p = change in momentum wall. Momentum || to wall does not change. Impulse will be wall. Take + direction toward wall, Impulse = p = m v = m[(- v sin θ ) - (v sin θ )] = -2mv sin θ = - 2.1 N s. Impulse on wall is in opposite direction: 2.1 N s . Problem 17 v i = v sin θ v f = - v sin θ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ppa6lecturech07-1217366224981674-9/85/Lecture-Ch-07-20-320.jpg)

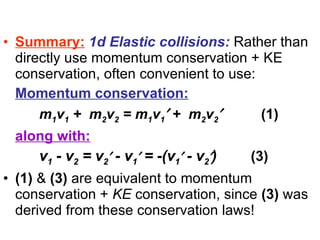

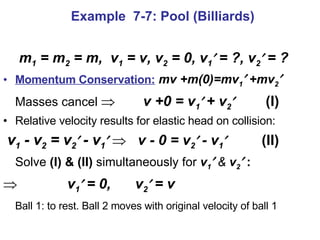

![m 1 v 1 + m 2 v 2 = m 1 v 1 + m 2 v 2 (1) (½)m 1 (v 1 ) 2 + (½)m 2 (v 2 ) 2 = (½)m 1 (v 1 ) 2 + (½) m 2 (v 2 ) 2 (2) Now, some algebra with (1) & (2 ), the results of which will help to simplify problem solving : Rewrite (1) as: m 1 (v 1 - v 1 ) = m 2 (v 2 - v 2 ) (a) Rewrite (2) as: m 1 [(v 1 ) 2 - (v 1 ) 2 ] = m 2 [(v 2 ) 2 - (v 2 ) 2 ] (b) Divide (b) by (a): v 1 + v 1 = v 2 + v 2 or v 1 - v 2 = v 2 - v 1 = -(v 1 - v 2 ) (3) Relative velocity before= - Relative velocity after Elastic head-on (1d) collisions only!!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ppa6lecturech07-1217366224981674-9/85/Lecture-Ch-07-25-320.jpg)

½ Ex. 7-10 & Prob. 32 (Inelastic Collisions)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ppa6lecturech07-1217366224981674-9/85/Lecture-Ch-07-29-320.jpg)