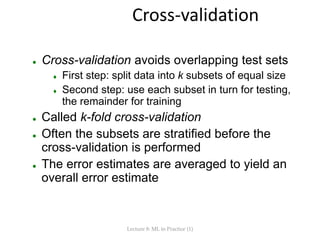

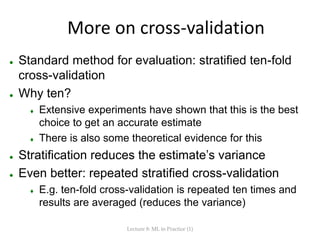

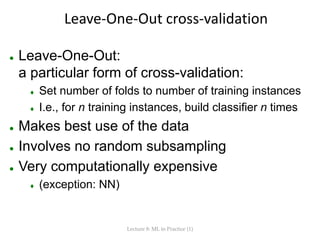

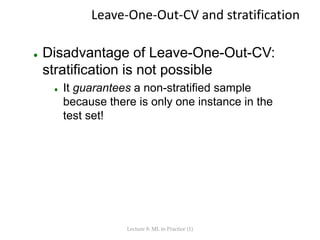

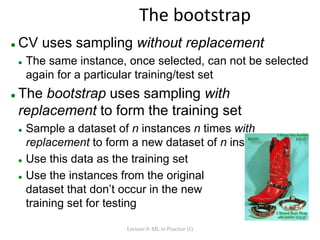

The document discusses the significance of feature representation in machine learning for language technology, emphasizing that the quality of features greatly influences model performance. It also covers practical steps for data processing, evaluation methods like cross-validation, and the challenges of working with unbalanced datasets. Additionally, it addresses the importance of understanding different evaluation techniques to ensure robust and accurate machine learning models.

![Practical Steps

[...] (tasks before here…)

• Select Data: Collect it together

• Preprocess Data: Format it, clean it, sample it so you can

work with it.

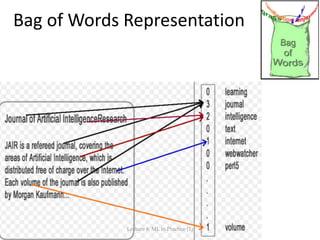

• Transform Data: FEATURE REPRESENTATION happens here.

• Model Data: Create models, evaluate them and tune them.

[...] (tasks after here…)

Lecture 8: ML in Practice (1)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture092015mlinpractice2completenoquizzes-151218095540/85/Lecture-9-Machine-Learning-in-Practice-2-10-320.jpg)