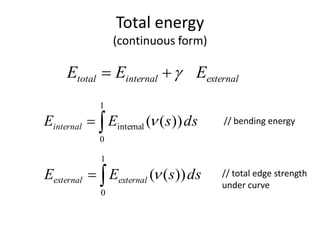

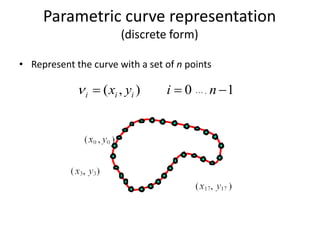

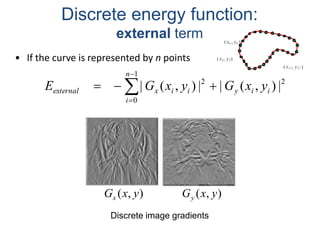

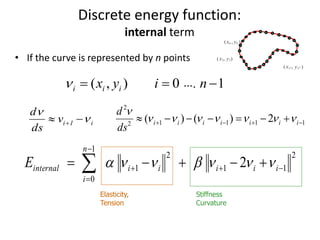

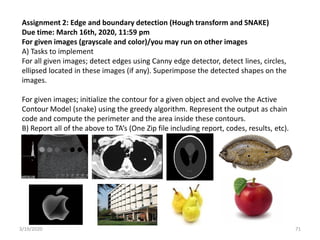

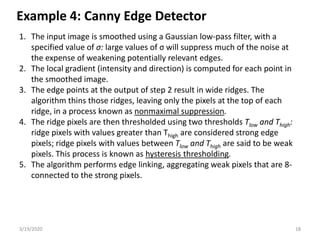

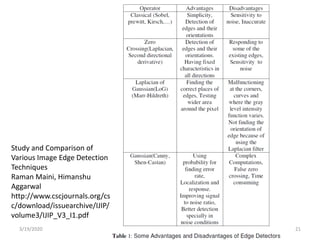

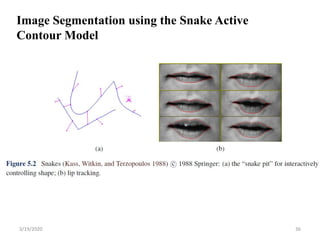

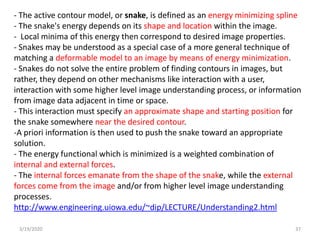

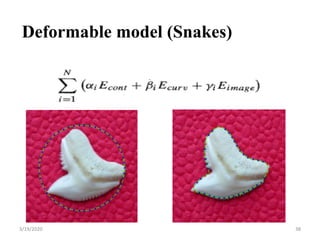

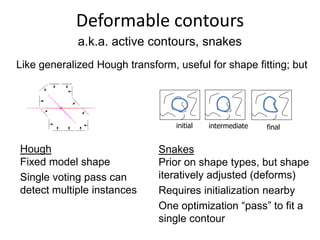

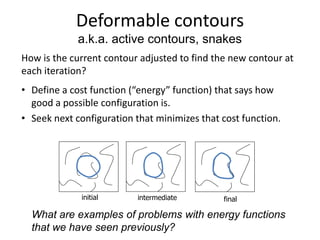

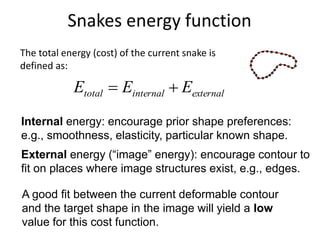

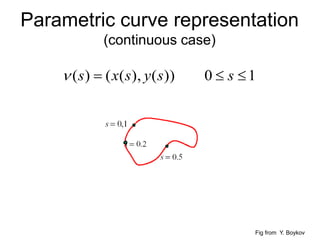

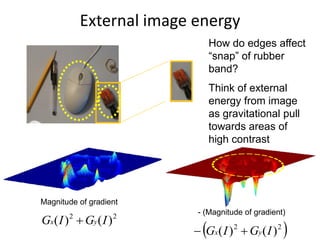

The document provides an overview of computer vision techniques including edge detection, edge representation using chain codes, line and circle detection using Hough transforms, and active contour deformable models (snakes). It describes several common edge detection algorithms like Prewitt, Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG), and Canny edge detectors. It also explains how the Hough transform can be used to detect lines and circles and discusses snakes, where an active contour model is defined as an energy minimizing spline that deforms to fit desired image properties by minimizing internal and external energy terms.

![3/19/2020 3

Edge Detection Goal: Could you point out the most “salient” or “strongest” edges or

the object boundaries? [Szeliski's Book p.210]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-3-320.jpg)

![3/19/2020 5

[Ch. 14, Practical Image and Video Processing Using MATLAB by Oge Marques]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-5-320.jpg)

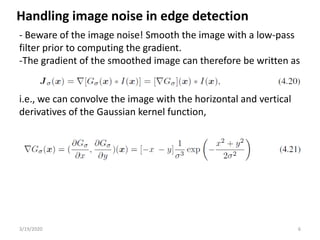

![3/19/2020 7

[Ch. 14,

Practical

Image

and Video

Processin

g Using

MATLAB

by Oge

Marques]

Even low noise levels can corrupt the edge detection operation…](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-7-320.jpg)

![3/19/2020 10

[Ch. 14,

Practical

Image and

Video

Processing

Using

MATLAB by

Oge

Marques]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-10-320.jpg)

![3/19/2020 11

- Estimate the gray-level gradient at a pixel, which can be approximated by the

digital equivalent of the first-order derivative as follows [Marques’ book, p.338]:

- The gradients are often computed within a 3×3 neighborhood using convolution:

where the Prewitt kernels are given by:

Example 1: Prewitt Edge Detector (First-order

Detector)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-11-320.jpg)

![3/19/2020 12

[Ch. 14,

Practical

Image

and

Video

Processi

ng Using

MATLAB

by Oge

Marque

s]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-12-320.jpg)

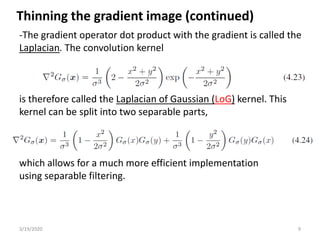

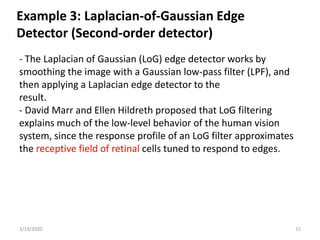

![3/19/2020 13

- The Laplacian operator is a straightforward digital

approximation of the second-order derivative of the intensity.

Although it has the potential for being employed as an isotropic

(i.e., omnidirectional) edge detector, it is rarely used in isolation

because of two limitations [Marques’ book, p. 343]:

• It generates “double edges,” that is, positive and negative

values for each edge.

• It is extremely sensitive to noise.

Example 2: Zero-crossing Edge Detector

(Second-order detector)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-13-320.jpg)

![3/19/2020 14

[Ch. 14,

Practical

Image

and

Video

Processi

ng Using

MATLAB

by Oge

Marque

s]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-14-320.jpg)

![3/19/2020 16

[Ch. 14,

Practical

Image

and

Video

Processi

ng Using

MATLAB

by Oge

Marque

s]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-16-320.jpg)

![3/19/2020 17

[Ch. 14,

Practical

Image

and

Video

Processi

ng Using

MATLAB

by Oge

Marque

s]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-17-320.jpg)

![3/19/2020 20

[Ch. 14,

Practical

Image

and

Video

Processi

ng Using

MATLAB

by Oge

Marque

s]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-20-320.jpg)

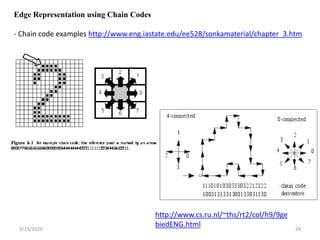

![3/19/2020 23

Edge Representation using Chain Codes [Szeliski's Book p.217]

- Linked edgel lists can be encoded more compactly using a variety of alternative

representations.

A chain code encodes a list of connected points lying on an N-8 grid using a

three-bit code corresponding to the eight cardinal directions (N, NE, E, SE, S, SW, W, NW)

between a point and its successor (Figure 4.34).

-While this representation is more compact than the original edgel list (especially if

predictive variable-length coding is used), it is not very suitable for further processing.

-See: Introduction to Chain Codes

http://www.mind.ilstu.edu/curriculum/chain_codes_intro/chain_codes_intro.php](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-23-320.jpg)

![3/19/2020 25

Edge Representation using Arc-Length Parameterization [Szeliski's Book p.217]

- A more useful representation is the arc length parameterization of a contour, x(s), where

s denotes the arc length along a curve (Figure 4.35).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-25-320.jpg)

![3/19/2020 26

Edge Representation using Arc-Length Parameterization [Szeliski's Book p.217]

- The advantage of the arc-length parameterization is that it makes matching and

processing (e.g., smoothing) operations much easier (Figure 4.36). Arc-length

parameterization can also be used to smooth curves in order to remove digitization noise.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-26-320.jpg)

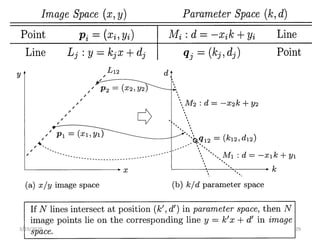

![3/19/2020 28

Points and lines

in image and

parameter spaces

http://books.google.com.eg/books/abou

t/Digital_Image_Processing.html?id=jCEi

9MVfxD8C&redir_esc=y

[Chapter 9]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-28-320.jpg)

![3/19/2020 30

Line Detection using Hough Tranform [Szeliski's Book p.221]

Motivation: Lines in the real world are sometimes broken up into disconnected

components or made up of many collinear line segments. In many cases, it is desirable to

group such collinear segments into extended lines.

Original Formulation: Each edge point votes for all possible lines passing through it, and

lines corresponding to high accumulator or bin values are examined for potential line fits.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-30-320.jpg)

![3/19/2020 31

Line Detection using Hough Tranform [Szeliski's Book p.222]

Alternate Formulation: Use the local orientation information at each edgel

to vote for a single accumulator cell.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-31-320.jpg)

![3/19/2020 32

Line Detection using Hough Tranform [Szeliski's Book p.223]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-32-320.jpg)

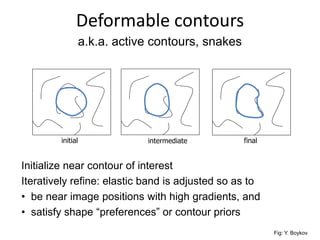

![Deformable contours

Given: initial contour (model) near desired object

a.k.a. active contours, snakes

(Single frame)

Fig: Y. Boykov

[Snakes: Active contour models, Kass, Witkin, & Terzopoulos, ICCV1987]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-39-320.jpg)

![Deformable contours

Given: initial contour (model) near desired object

a.k.a. active contours, snakes

(Single frame)

Fig: Y. Boykov

Goal: evolve the contour to fit exact object boundary

[Snakes: Active contour models, Kass, Witkin, & Terzopoulos, ICCV1987]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-40-320.jpg)

![Dealing with missing data

• The smoothness constraint can deal with missing data:

[Figure from Kass et al. 1987]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture-45-sbe404edgedetectioncodechainshoughtransformsnakes-200821100417/85/Lecture-4-5-computer-vision-edge-detection-code-chains-hough-transform-snakes-55-320.jpg)