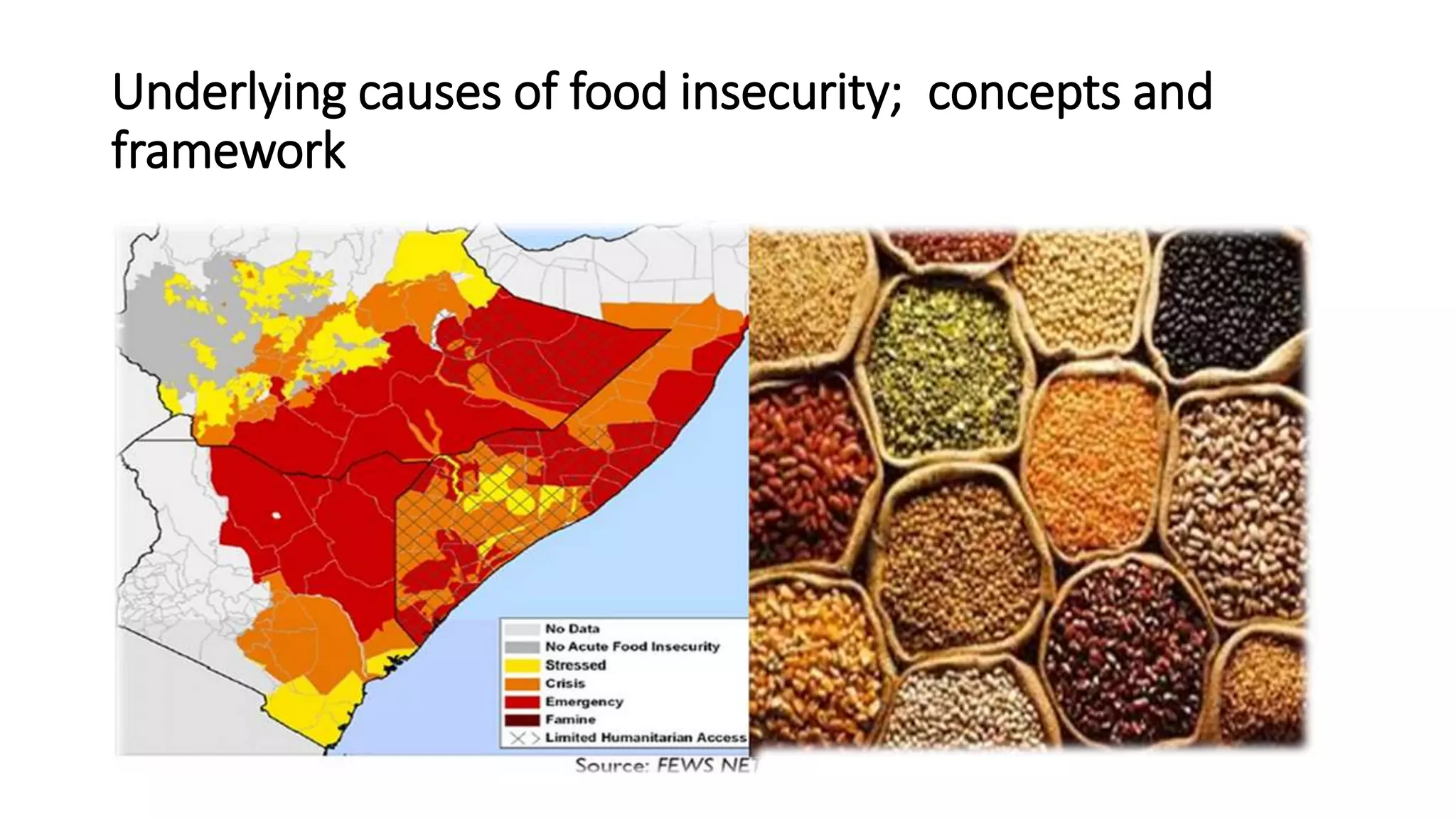

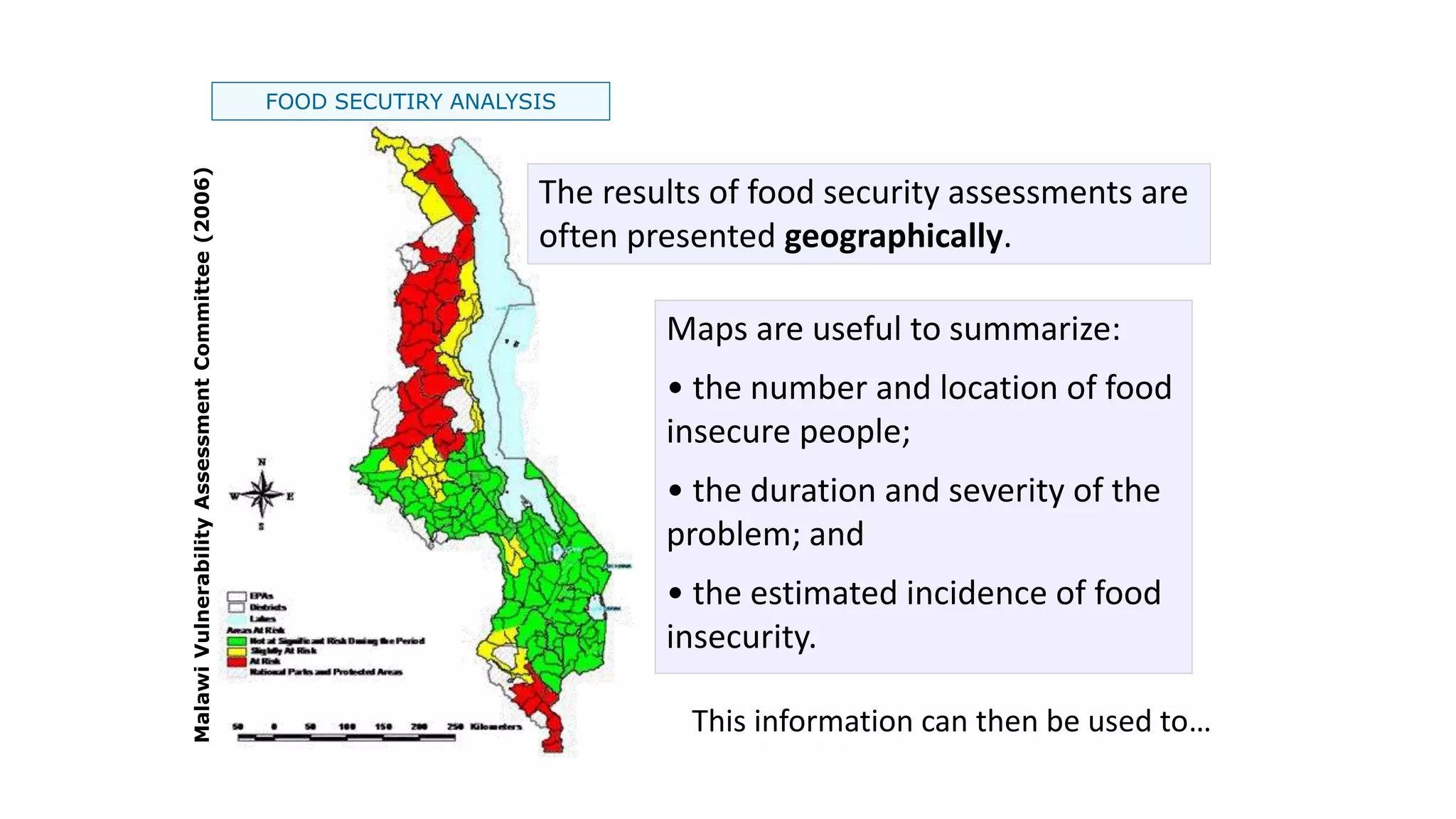

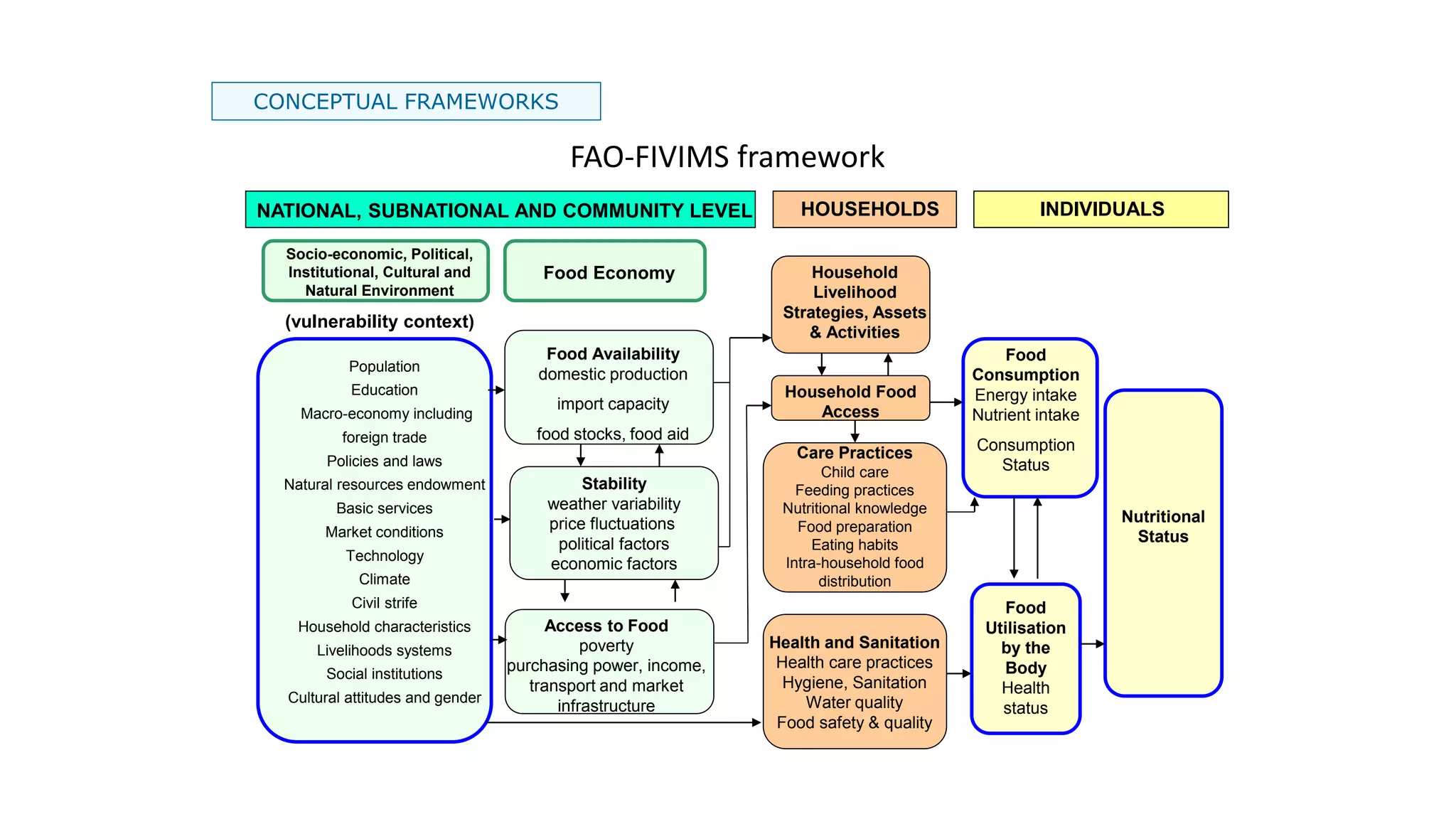

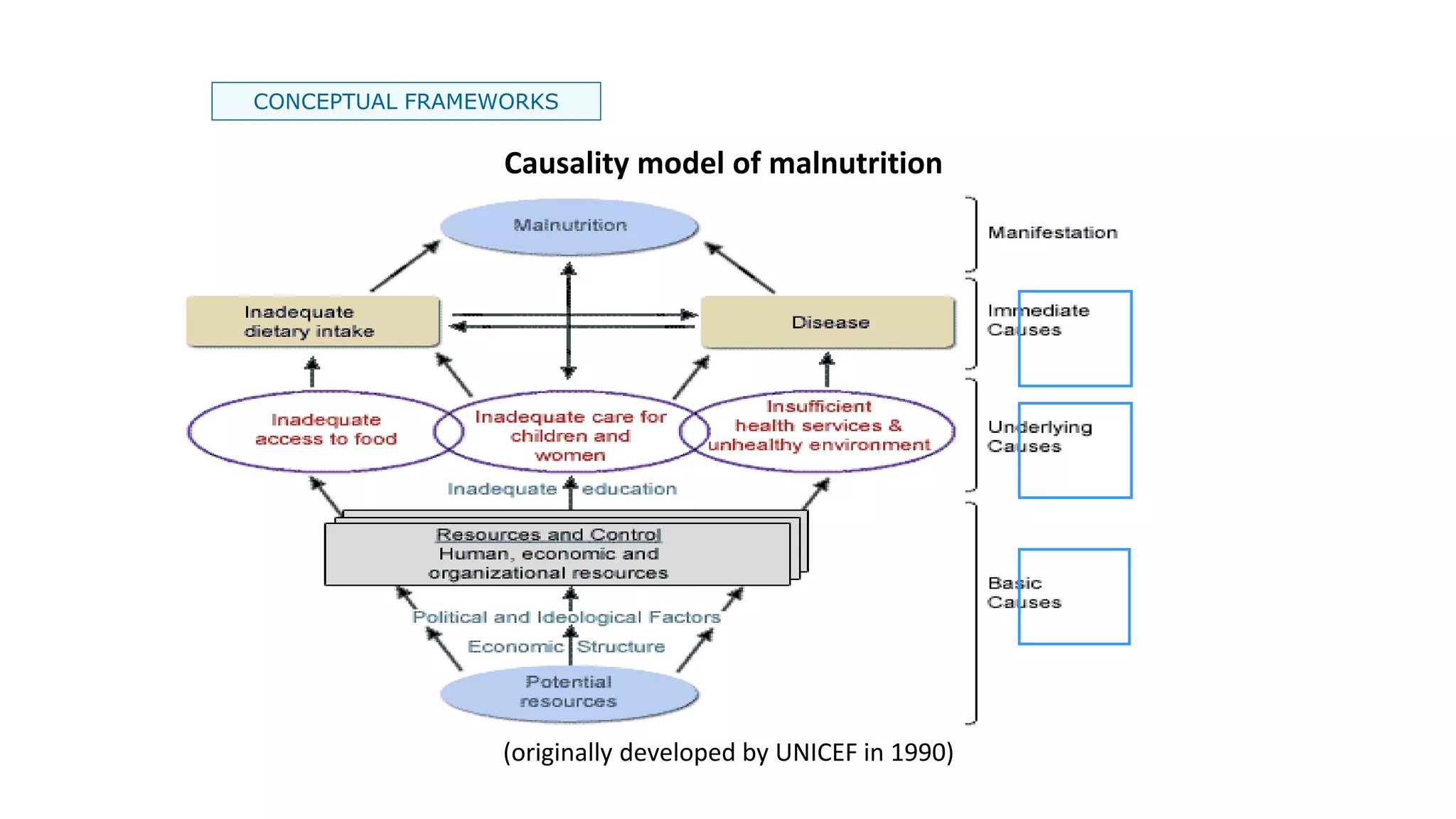

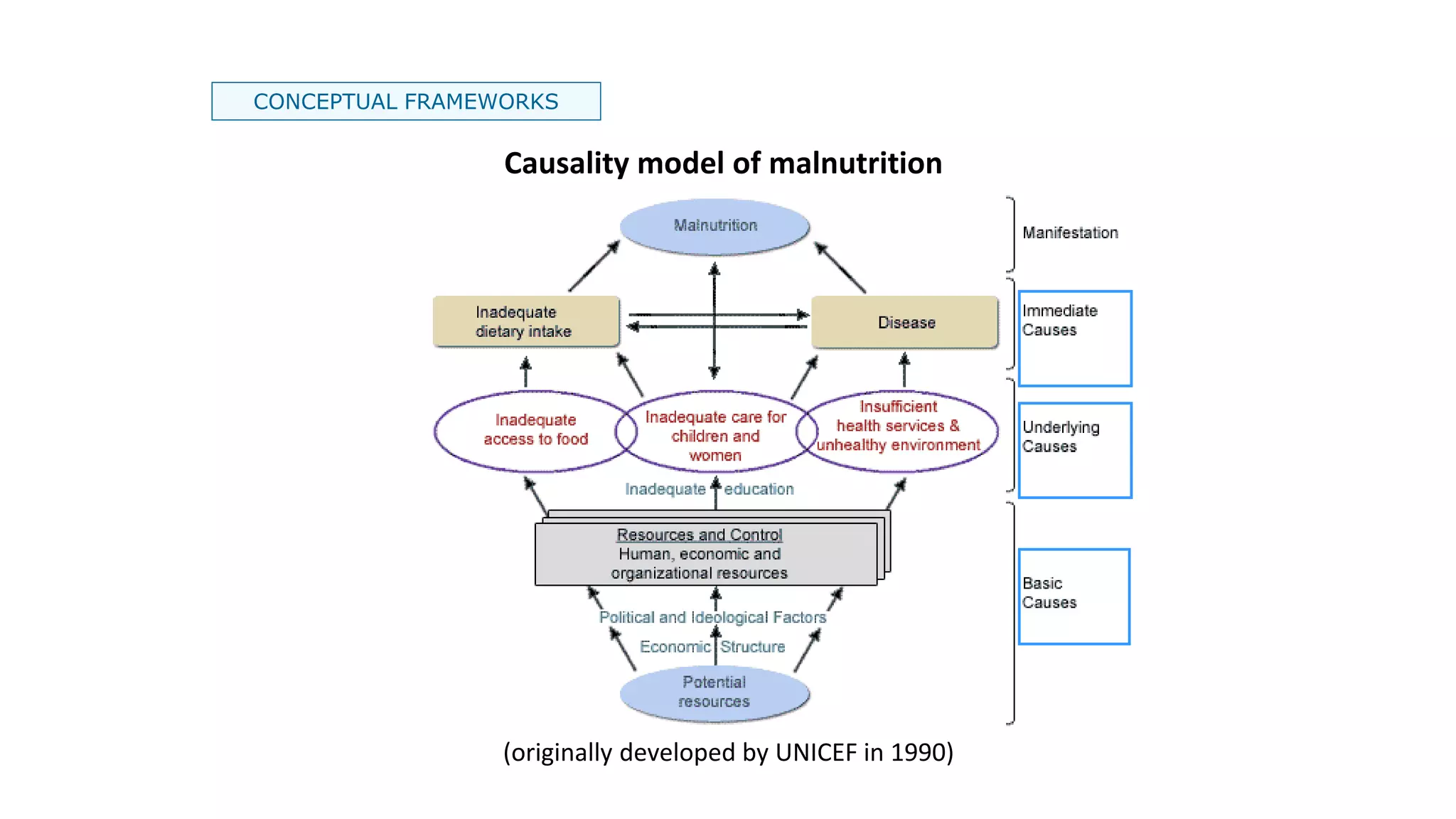

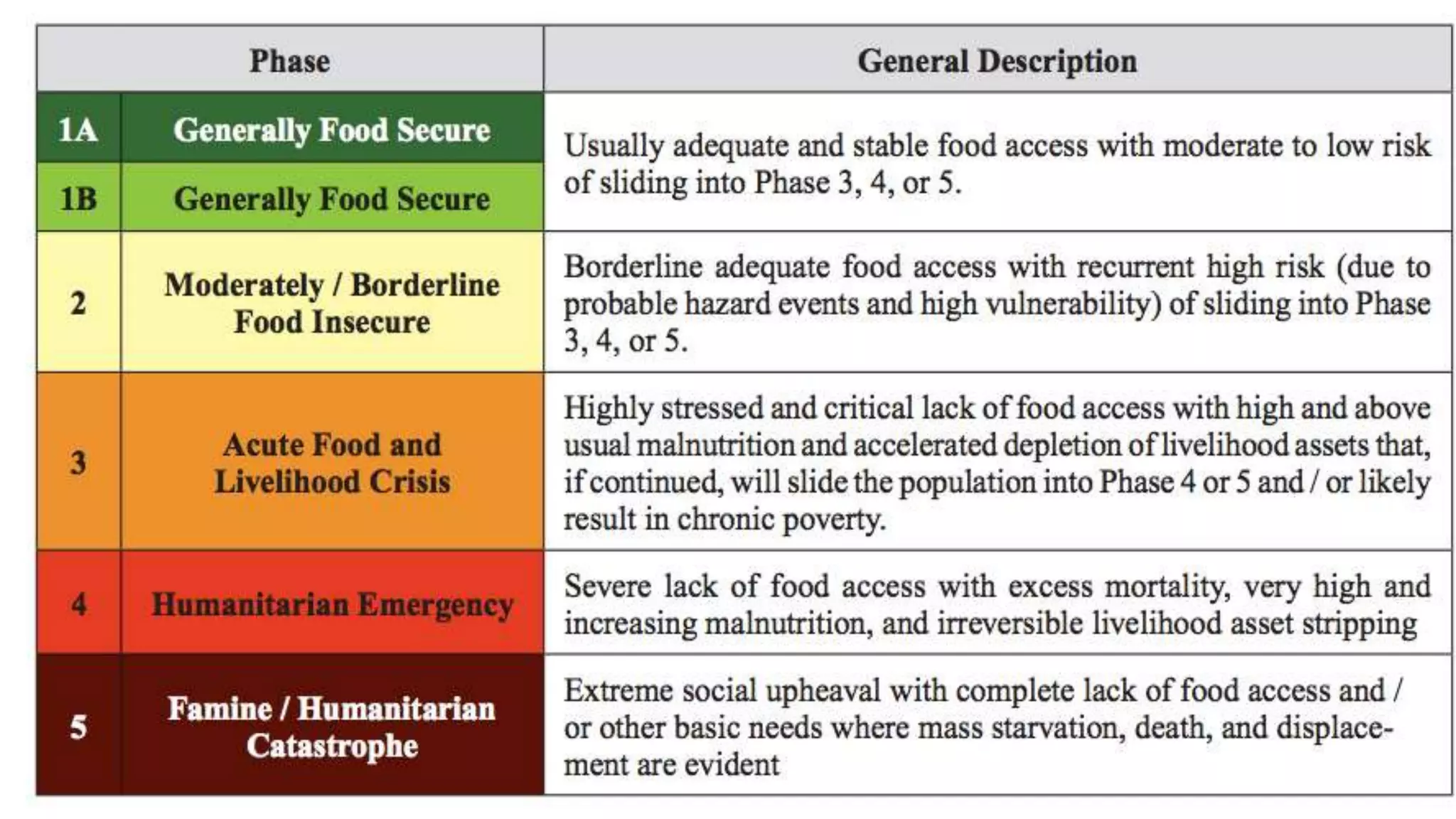

Food insecurity remains a global challenge. Achieving food security requires accurately measuring the incidence, nature, and causes of food insecurity. This allows for prioritizing interventions and targeting assistance. Conceptual frameworks help analyze the complex underlying causes of food insecurity and guide appropriate responses. Understanding factors like availability, access, utilization, and stability is key to selecting interventions to address problems like inadequate food, care practices, or health environments.