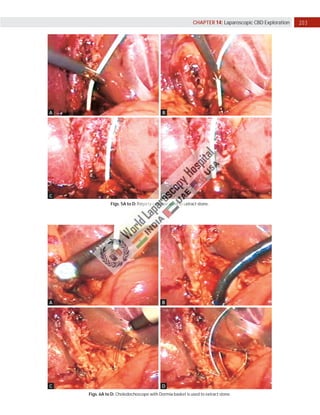

Laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct (CBD) is essential for diagnosing and treating CBD stones, utilizing intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) and laparoscopic ultrasonography (LUS). While IOC has high accuracy for detecting CBD stones, LUS offers quicker results with better specificity, yet is less precise in detailing biliary anatomy. The choice of technique depends on factors such as duct anatomy, size, and stone location, with the potential for laparoscopic transcystic approaches to be favored for small stones, while larger stones may necessitate choledochotomy.