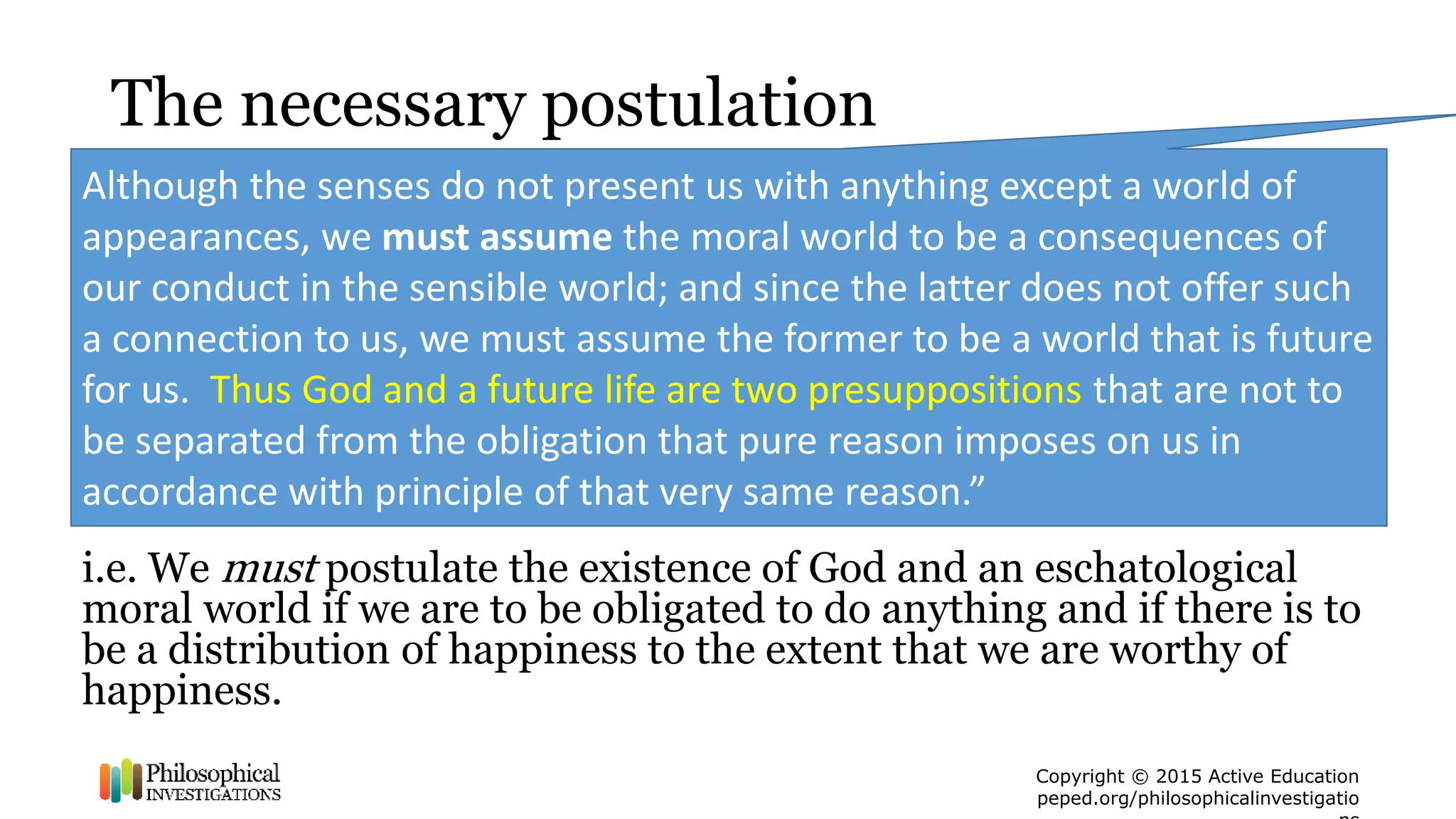

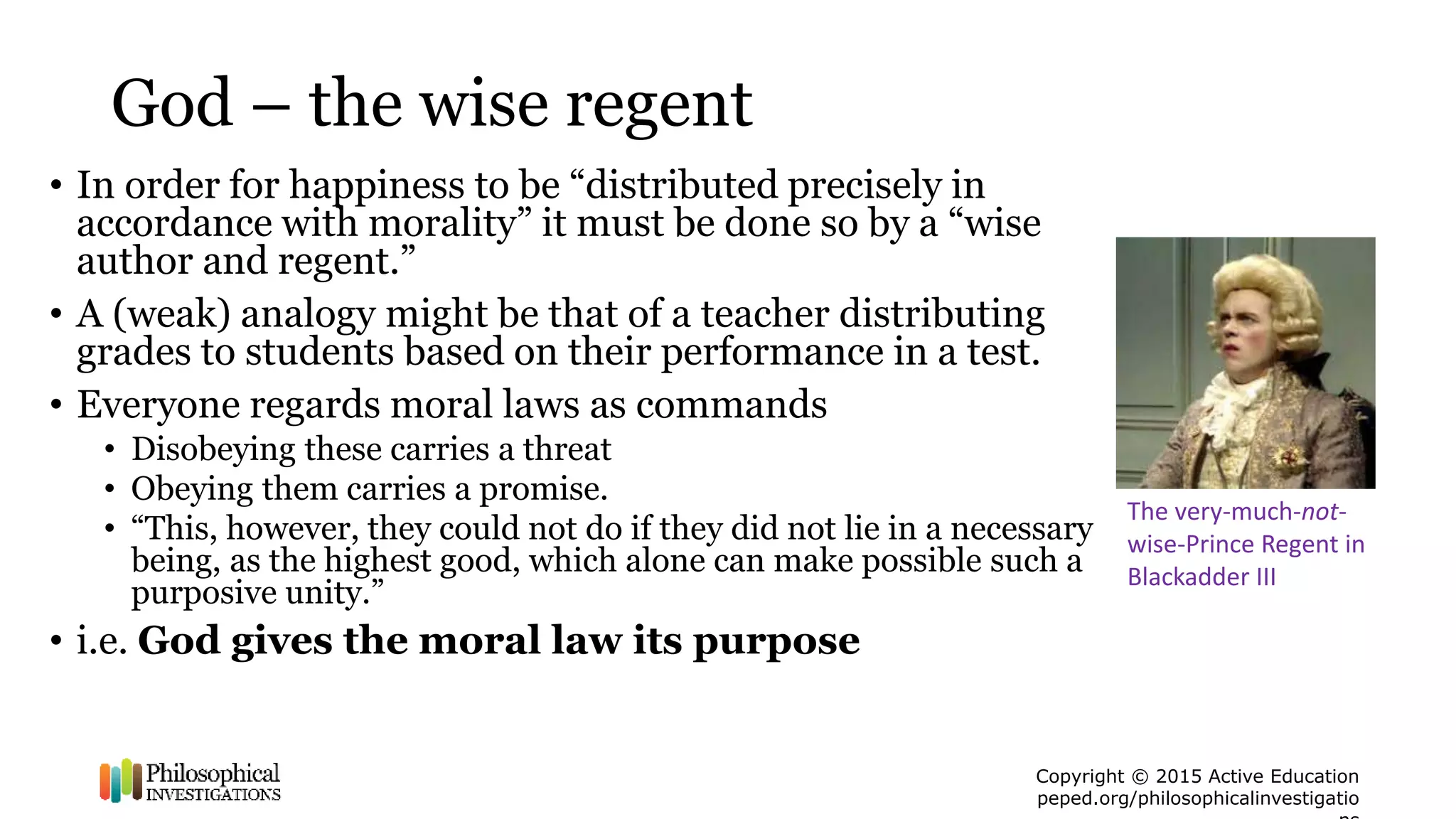

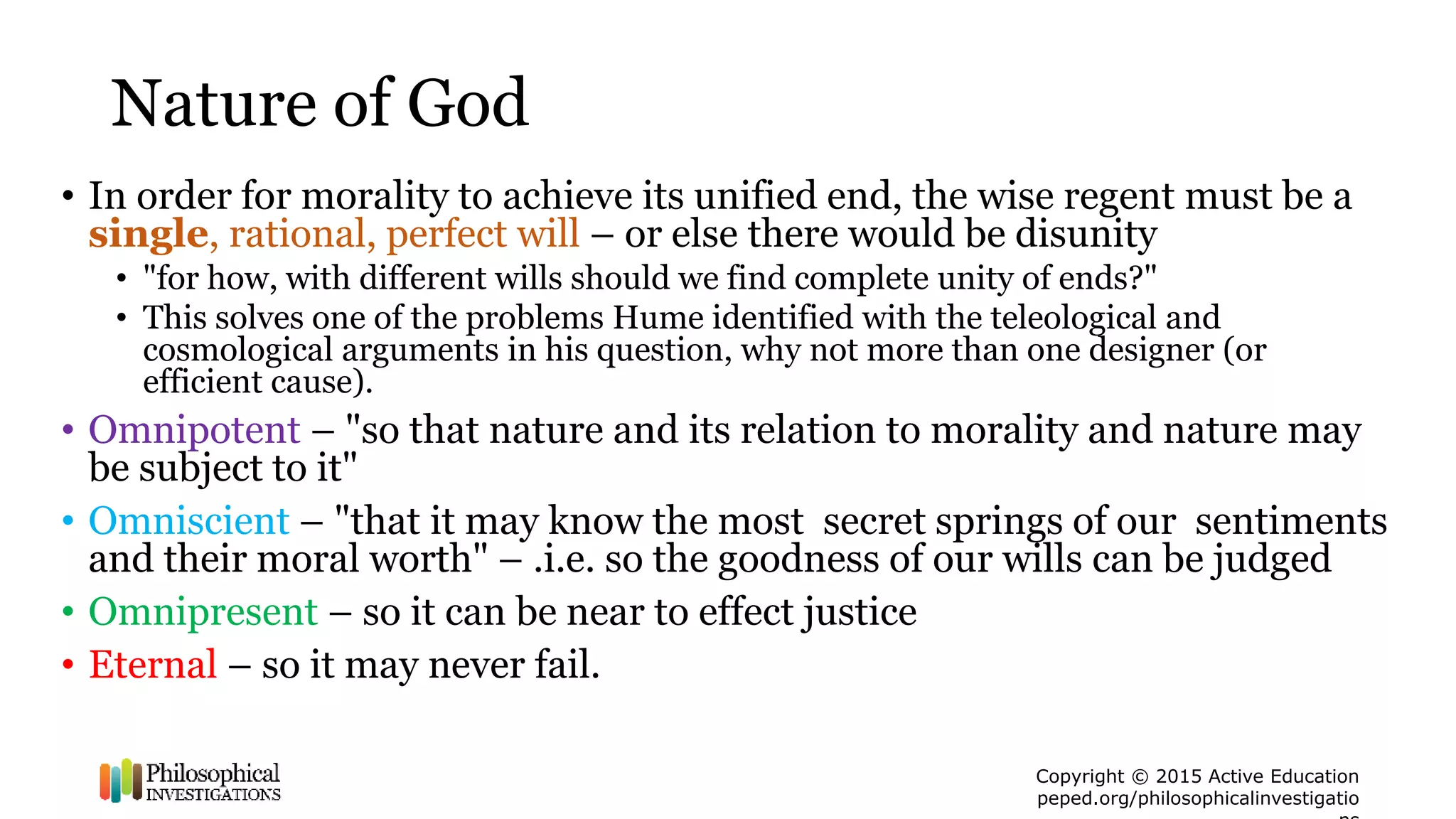

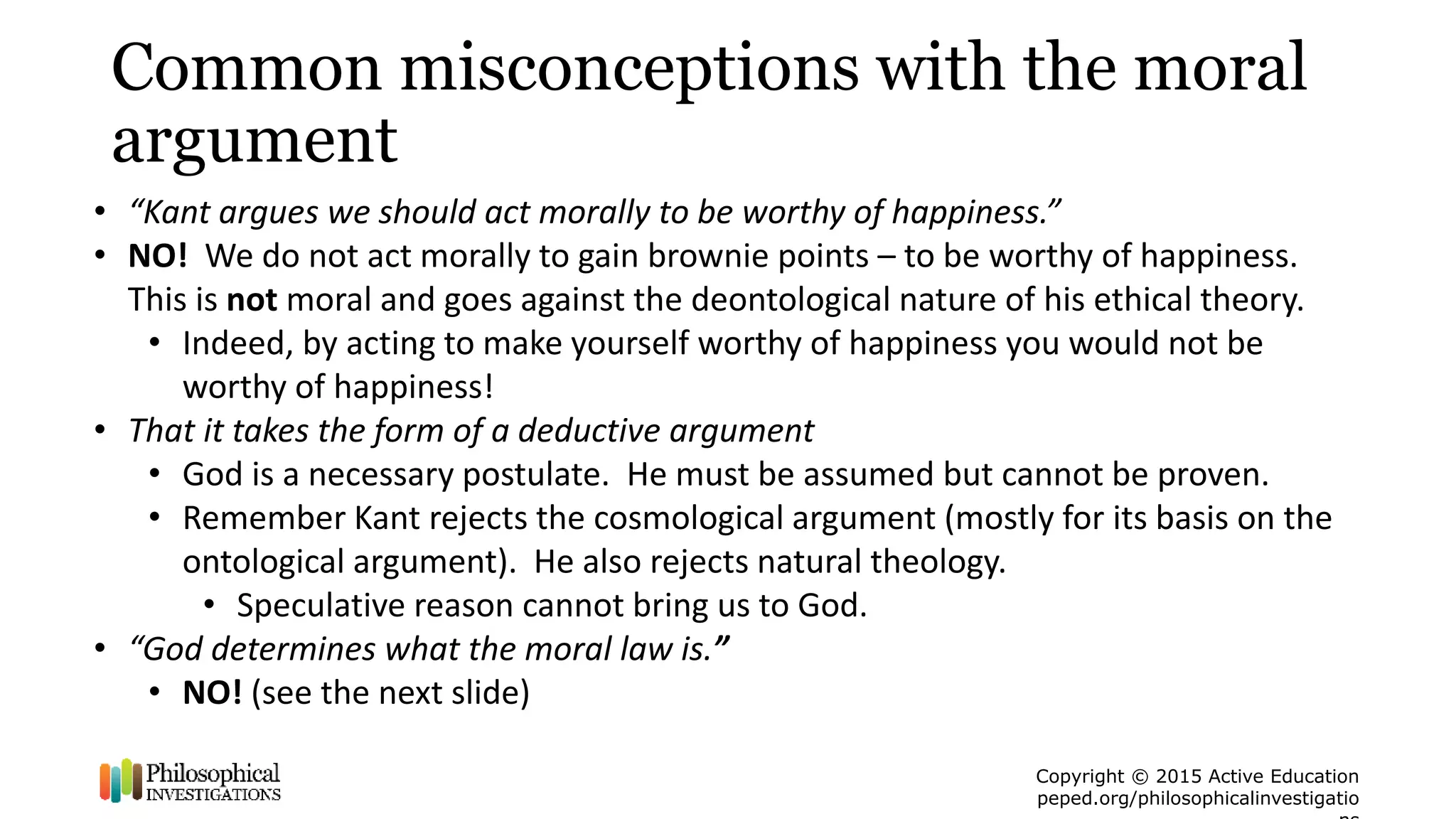

Kant's moral argument posits that the existence of God is necessary for morality to achieve its purpose, as true happiness must be distributed according to worthiness, which requires a wise regent. He asserts that moral obligations can only be meaningful in a future world where moral laws align with a divine ideal, rejecting moral actions as mere means to happiness. Ultimately, Kant emphasizes that morality is autonomous, deriving from reason rather than divine command, and concludes that God is an indispensable postulate of pure practical reason.

![Copyright © 2015 Active Education

peped.org/philosophicalinvestigatio

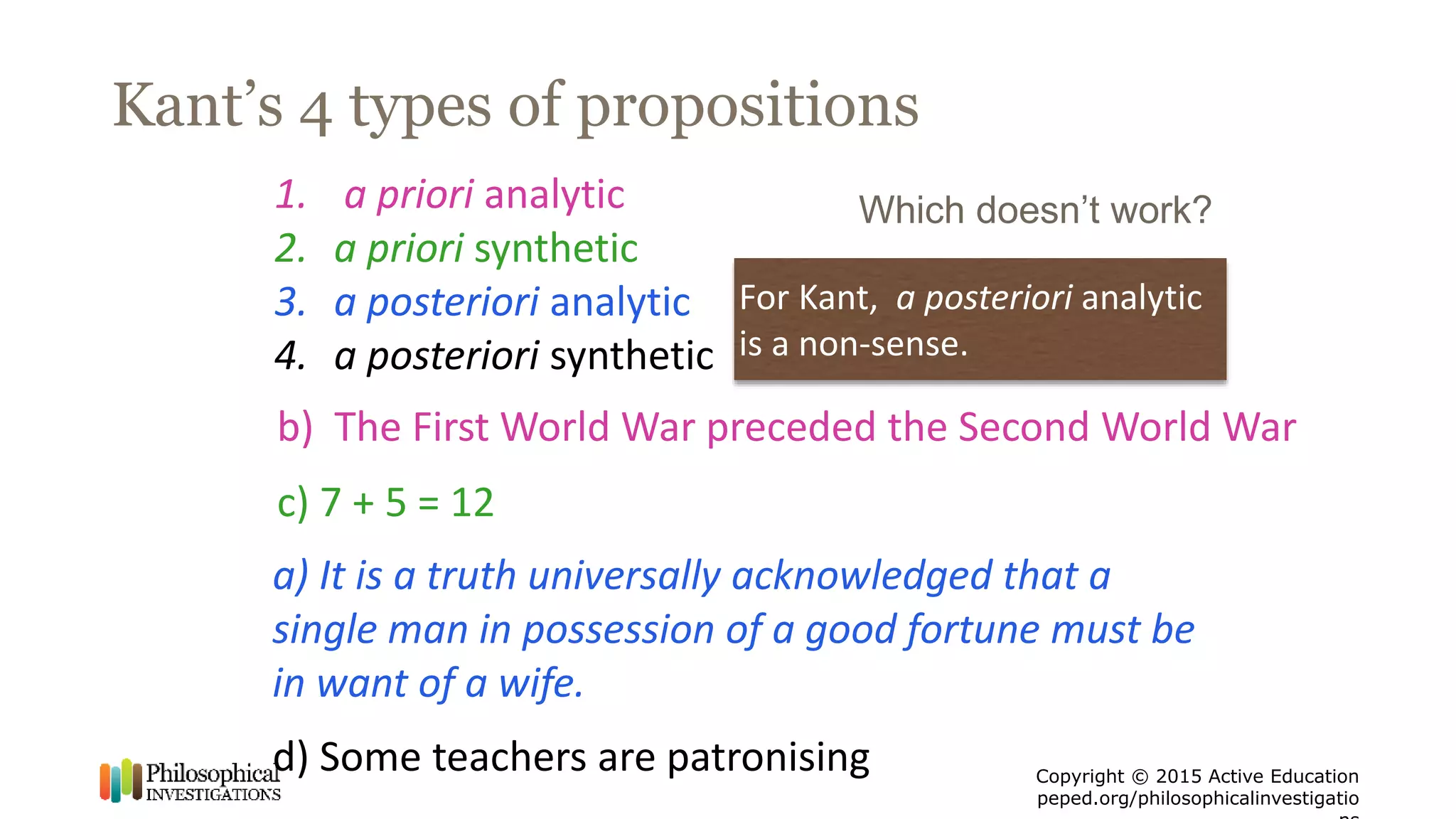

Analytic and synthetic statements

• Analytic = The subject concepts contain the predicate* concept.

• E,g, the concept of a bachelor contains the notion of being unmarried [unless you’re talking

about a Bachelor of Arts]

• Thus true or false by definition “all bodies are extended” (i.e. occupy space).

• Synthetic = The subject concepts do not contain the predicate concept:

• the concept of a rich bachelor does not contain notion of his desiring a wife . [cf Pride and

Prejudice!]

• Thus true or false empirically e.g. “All bodies are heavy.”

• Question: “all unicorns are white” – analytic or synthetic?

*A predicate is something that is being attributed to a subject, such as the sharpness of a

knife or the wisdom of the fool.

NB Ayer seems to use the terms Analytic & Synthetic slightly differently in the 20th Century](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kantmoralargument-160309144840/75/Kant-s-Moral-Argument-for-the-existence-of-God-5-2048.jpg)

![Copyright © 2015 Active Education

peped.org/philosophicalinvestigatio

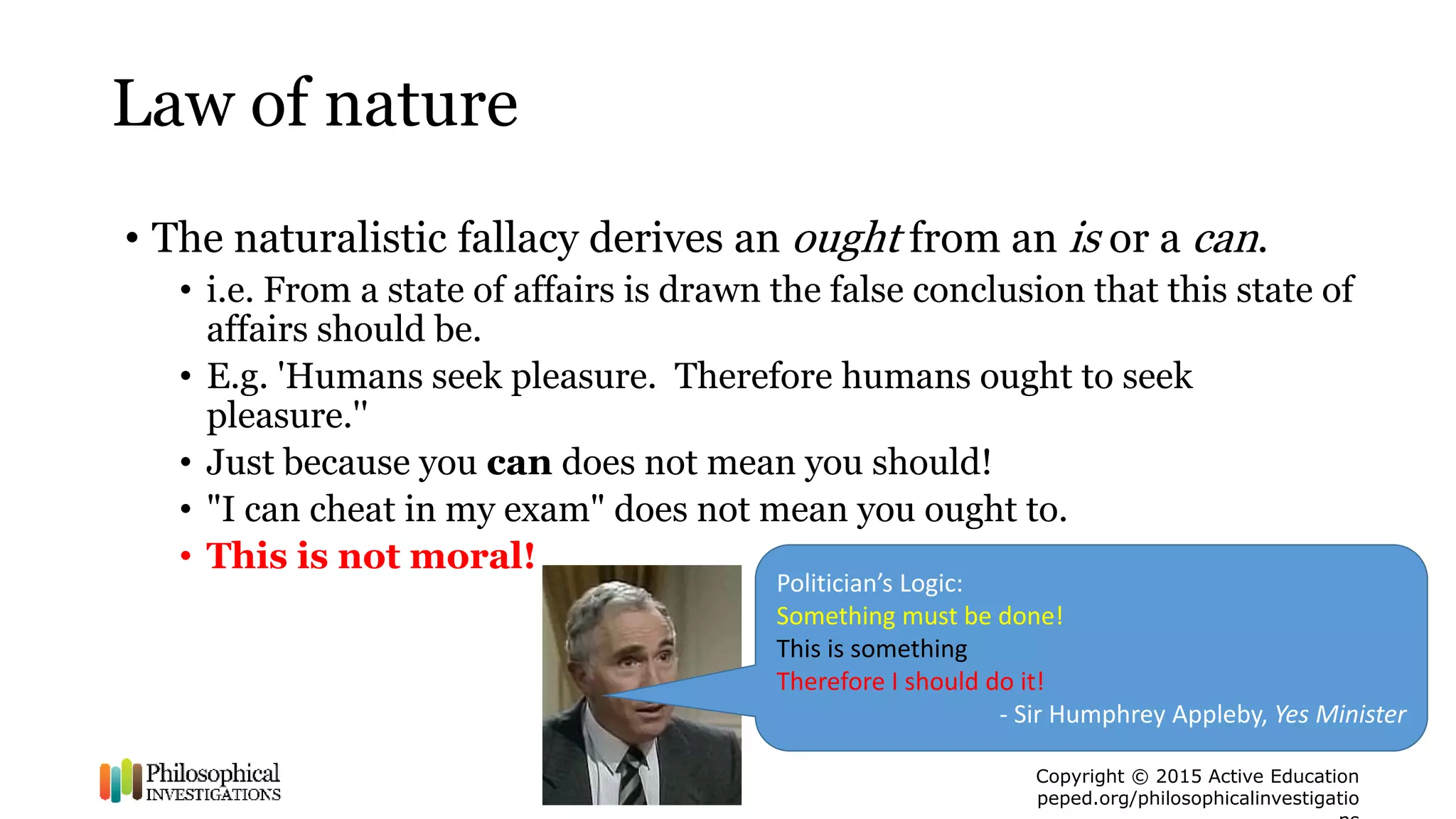

The law of prudence

• Doing something in order to achieve some end “from the motive of

happiness.”

• E.g I will revise because it might help me pass my exam

• Sounds like Bentham!

• Kant recognises that we are often driven by this law.

• His example: we sometimes decide not to lie because we realise that we

might not be trusted in the future if found out – it would not benefit us in

the future and thus is not prudent.

• However this is stupid because we cannot be certain what will make us

happy. "[Man] is not capable of determining with complete certainty, in

accordance with any principle, what will make him truly happy, because

omniscience would be required for that."

• This is not moral !](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kantmoralargument-160309144840/75/Kant-s-Moral-Argument-for-the-existence-of-God-11-2048.jpg)

![Copyright © 2015 Active Education

peped.org/philosophicalinvestigatio

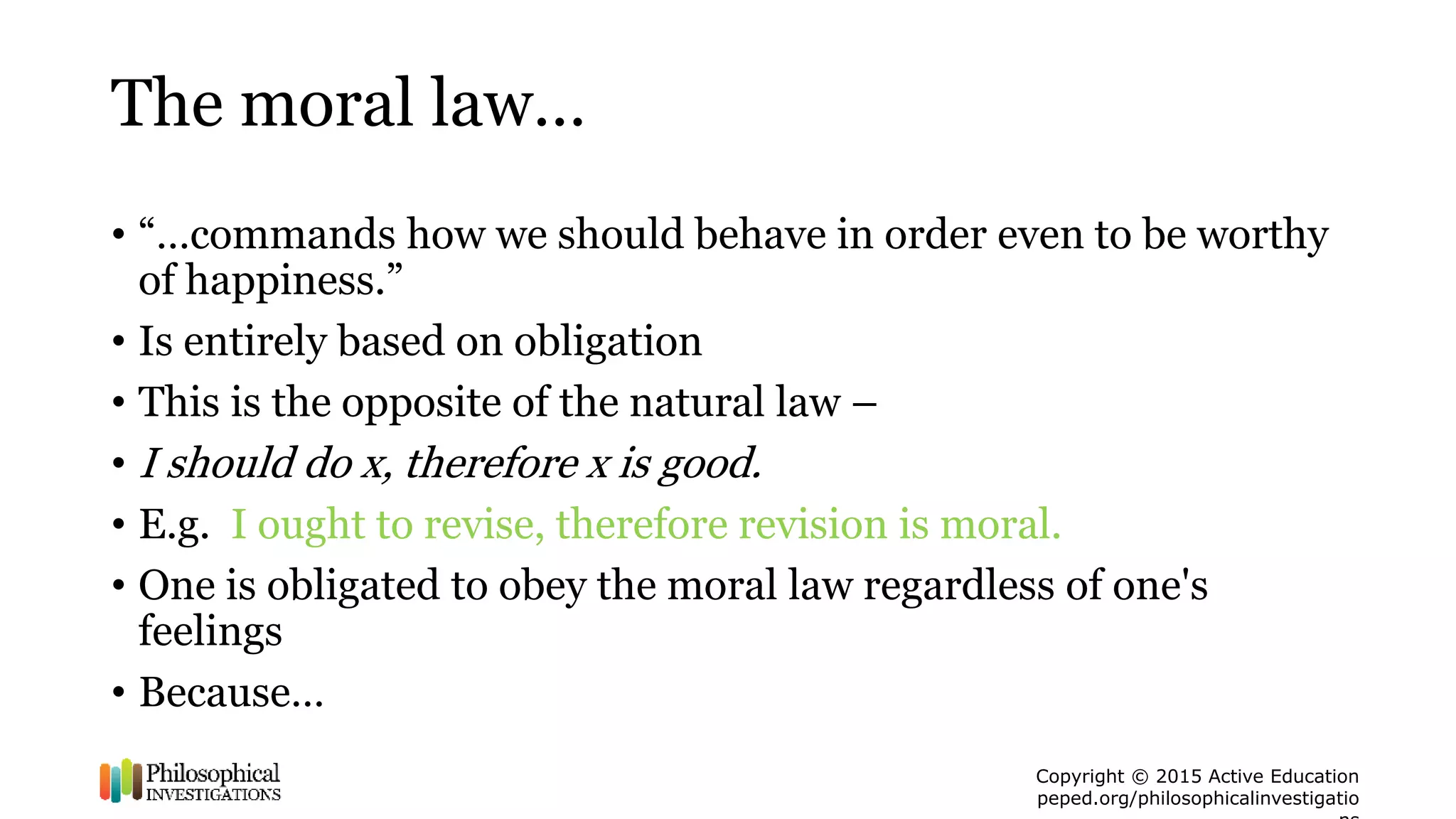

Ought implies can

• If we are to be obliged to do something, it must be possible for

us to do.

• We cannot be obliged to fly out of a window since cannot do it!

• I ought to do the washing up

• It must be possible for me to do so.

• However, it is not always possible to be moral in this world

For since [moral precepts] command that these actions ought to happen,

they must also be able to happen, and there must therefore be possible a

special kind of systematic unity, namely the moral.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kantmoralargument-160309144840/75/Kant-s-Moral-Argument-for-the-existence-of-God-17-2048.jpg)

![Copyright © 2015 Active Education

peped.org/philosophicalinvestigatio

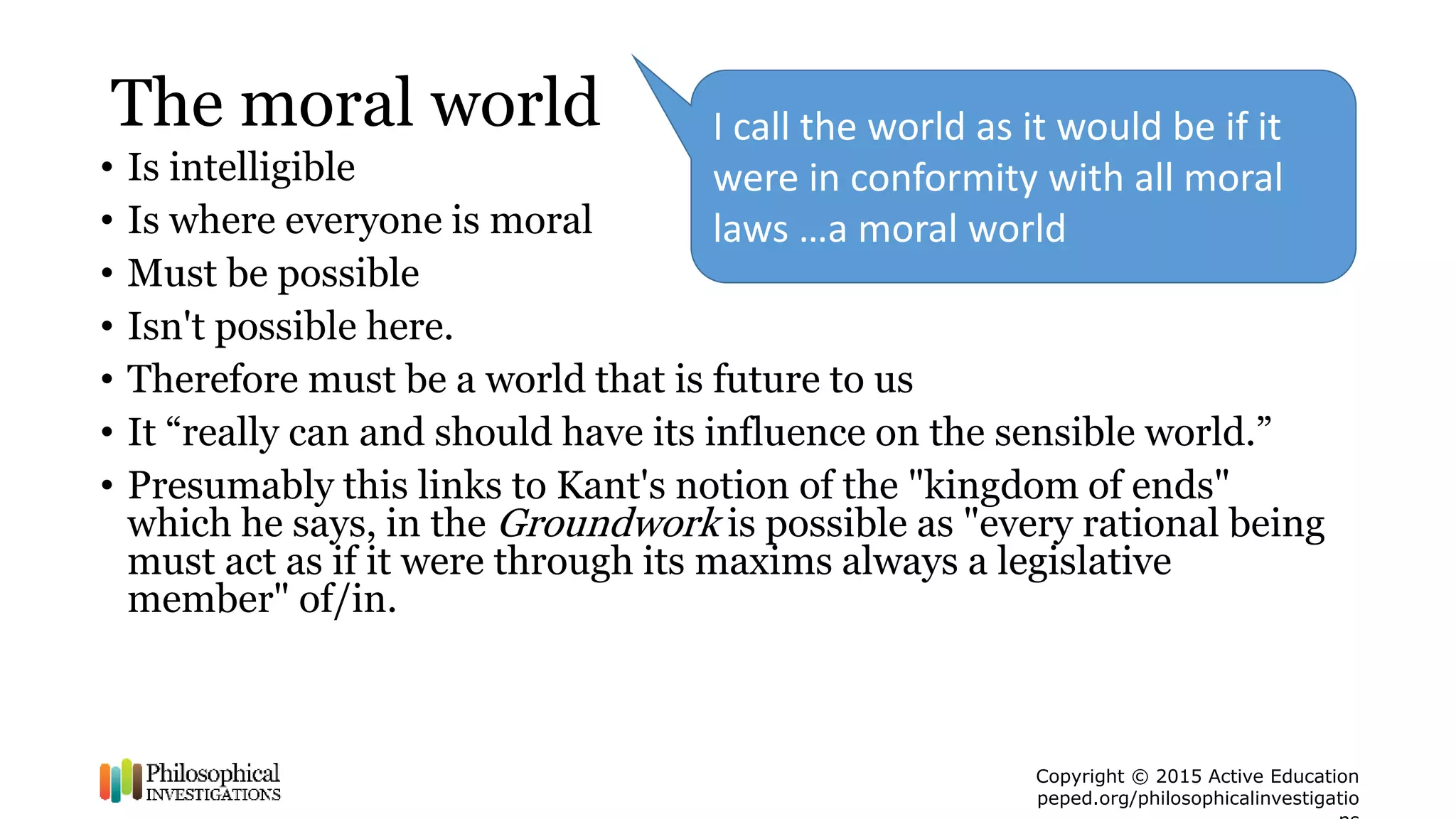

A Caveat

• Having arrived at the necessary postulation of God, we cannot

then start from God and work backwards – in some sort of

Divine Command Theory.

• “Now when practical reason has attained this high point, namely the

concept of a single original being as the highest good, it must not

undertake to start out from this concept and derive the moral laws

themselves from it.”

• It was “these [moral] laws alone whose inner practical necessity led us

to the presupposition of a self-sufficient cause or a wise world-regent in

order to give effect to these laws.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/kantmoralargument-160309144840/75/Kant-s-Moral-Argument-for-the-existence-of-God-27-2048.jpg)