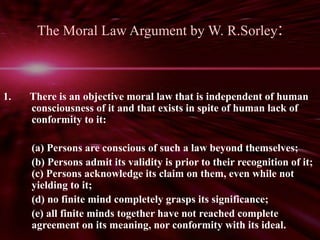

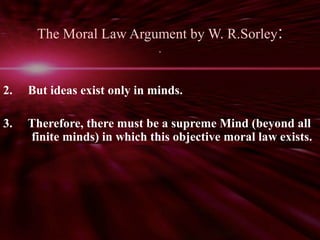

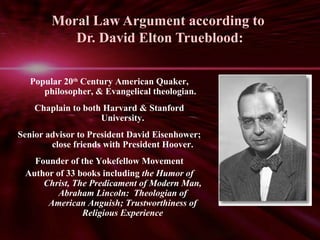

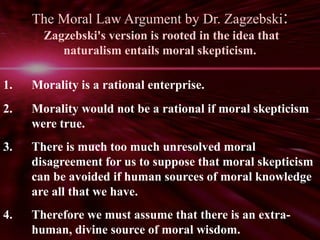

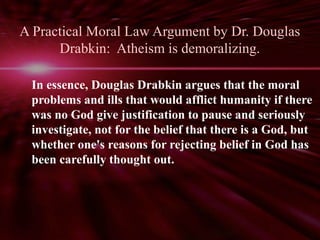

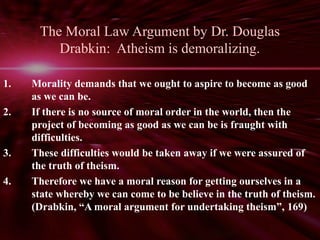

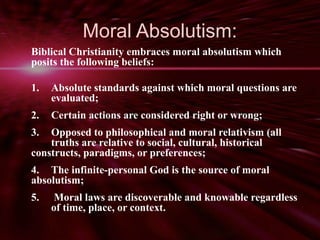

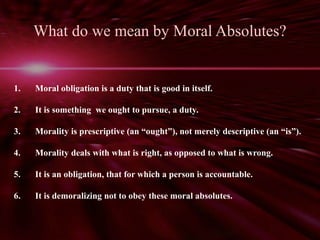

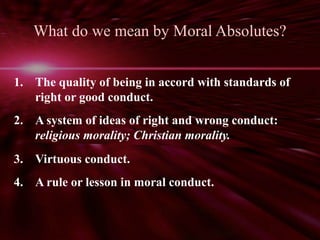

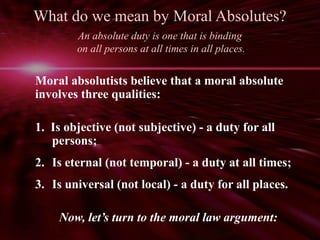

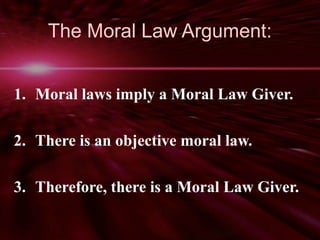

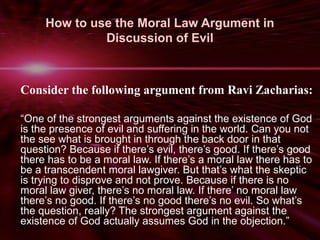

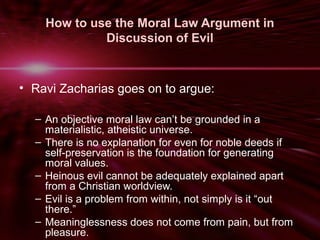

This document provides an overview of the moral law argument for the existence of God. It discusses various formulations of the argument by philosophers such as Hastings Rashdall, W.R. Sorley, Elton Trueblood, Linda Zagzebski, Robert Adams, and Douglas Drabkin. The moral law argument posits that the existence of objective moral absolutes implies a divine moral lawgiver. If there are universal moral truths, they require a transcendent source outside of human subjective opinions and cultural relativism. The document examines different logical formulations of this argument and responses to objections about the possibility of morality without God.

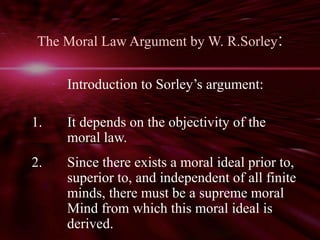

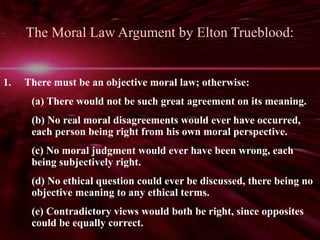

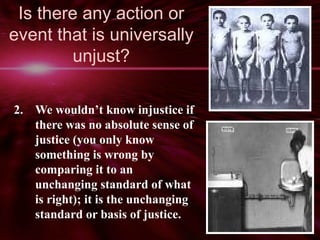

![The Standard of Justice

[As an atheist] my argument

against God was that the

universe seemed so cruel

and unjust. But how had I

got this idea of just and

unjust? A man does not call

a line crooked unless he has

some idea of a straight line.

What was I comparing this

universe with when I called

it unjust?

Straight Line = Standard

C.S. Lewis

Mere Christianity, p 45.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture8morallawargument-140908022445-phpapp02/85/Lecture-8-moral_law_argument-12-320.jpg)

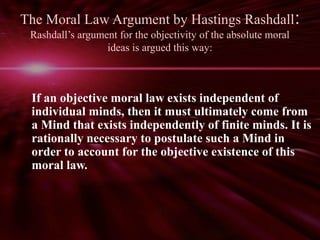

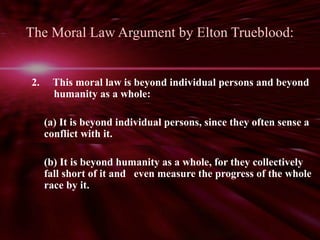

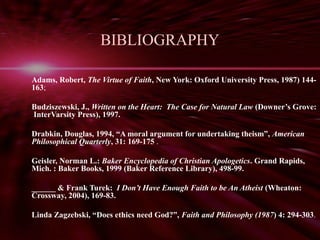

![The Moral Law Argument by Hastings Rashdall

(1858-1924):

Beginning with the objectivity of the moral law, Rashdall reasons

to an absolutely perfect Mind:

1. An absolutely perfect moral ideal exists (at least

psychologically in our minds).

2. An absolutely perfect moral law can exist only if there is an

absolutely perfect moral Mind:

(a) Ideas can exist only if there are minds (thoughts depend on

thinkers).

(b) And absolute ideas depend on an absolute Mind (not on

individual [finite] minds like ours).

3. Hence, it is rationally necessary to postulate an absolute Mind

as the basis for the absolutely perfect moral idea.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture8morallawargument-140908022445-phpapp02/85/Lecture-8-moral_law_argument-25-320.jpg)