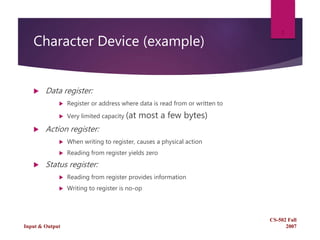

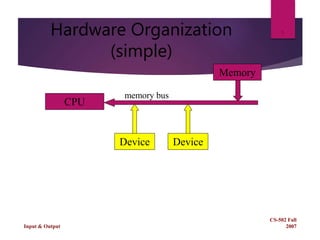

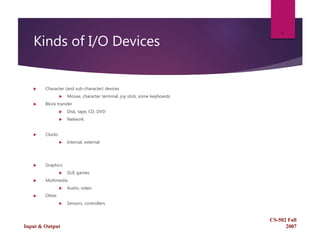

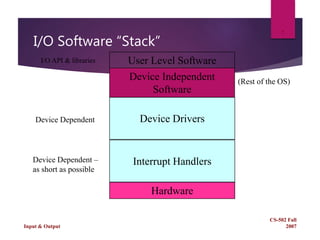

This document discusses character devices in Linux. It explains that character devices have three main registers: a data register for reading and writing small amounts of data, an action register that triggers a physical action when written to but returns zero when read, and a status register that provides information when read but is a no-op when written to. It then provides an overview of input/output in operating systems generally.