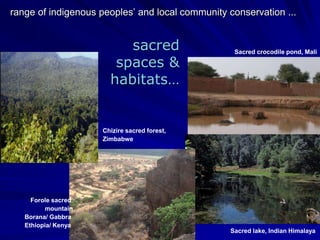

The document discusses the crucial role of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in global conservation efforts, highlighting their management of diverse ecosystems. It emphasizes the importance of Indigenous and community-conserved territories (ICCAs) in maintaining biodiversity and cultural identities, while detailing challenges they face due to legal recognition and development pressures. Recommendations for strengthening ICCAs include improved legal frameworks, recognition of traditional governance, and support for sustainable livelihoods.