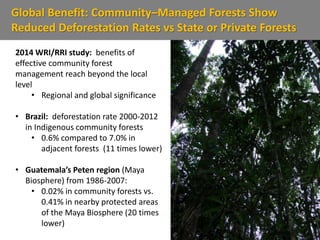

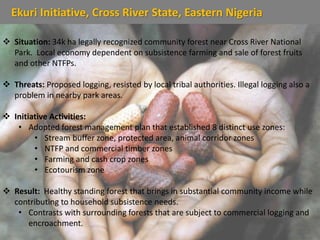

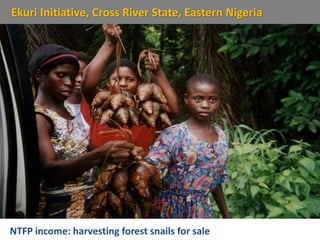

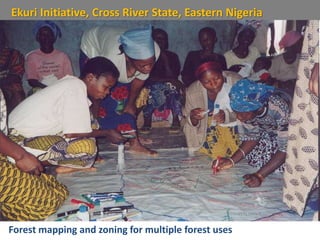

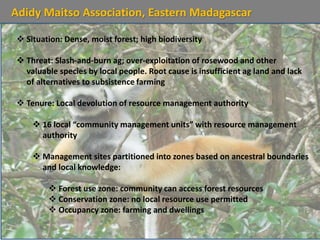

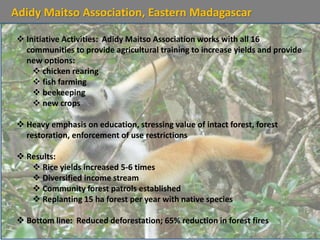

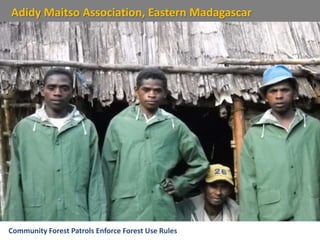

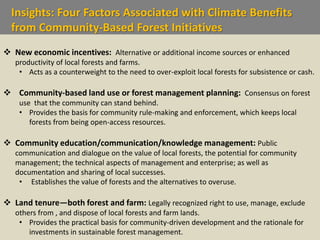

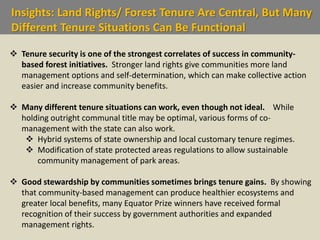

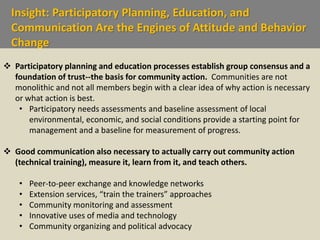

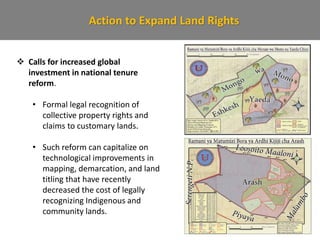

The document highlights the critical role of forest communities in providing climate solutions through community-based forest management, emphasizing their importance in climate mitigation and adaptation. It discusses successful case studies and initiatives that showcase the benefits of sustainable forest use, restoration, and protection, while advocating for expanded land rights and recognition of indigenous and local management practices in global climate policy. The overall message stresses the need for a landscape approach that integrates agriculture with forest management to enhance climate resilience and community well-being.