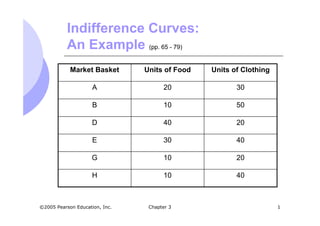

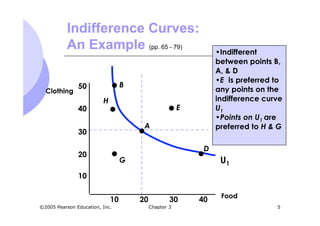

The document describes indifference curves and how they relate to consumer preferences between combinations of goods. It provides examples of indifference curves for clothing and food. Indifference curves show combinations of goods a consumer is indifferent between, and slope downward to the right since more is preferred to less. Their shape indicates how willing a consumer is to substitute one good for another. The marginal rate of substitution measures this willingness to substitute and captures the slope of the indifference curve. Perfect substitutes have a constant marginal rate of substitution, while perfect complements have right-angle shaped indifference curves. Utility and utility functions are also introduced to numerically represent satisfaction from market baskets. Budget constraints limit the combinations of goods that are affordable.

![Chapter 3 19©2005 Pearson Education, Inc.

Marginal Rate of Substitution (pp. 65

- 79)

Indifference curves with different shapes

imply a different willingness to substitute

[That is, an indifference map is a concept

to represent one’s preference for market

baskets.]

Two polar cases are of interest

Perfect substitutes

Perfect complements](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icpdf1-161126054229/85/Indifference-Curve-19-320.jpg)