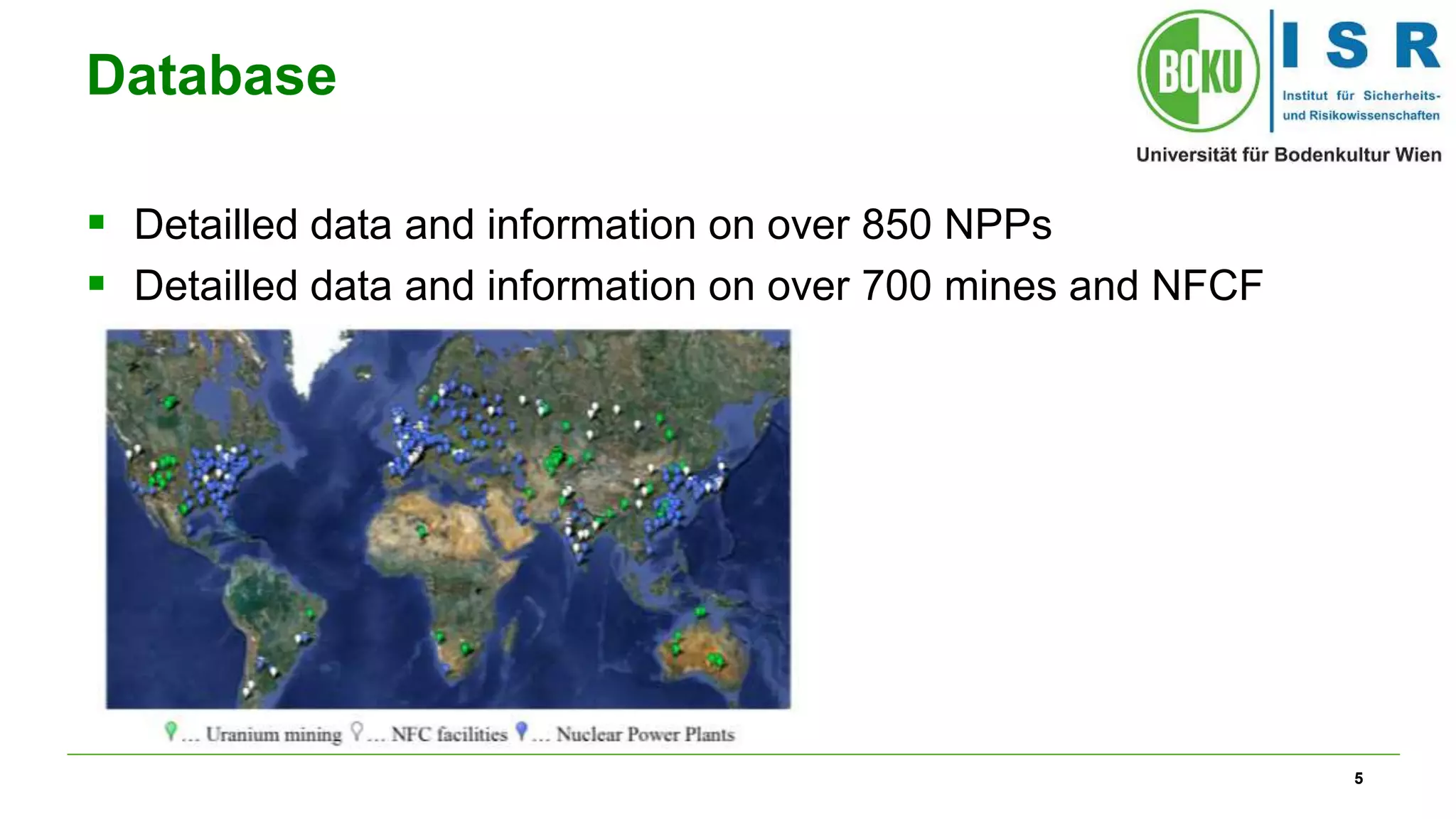

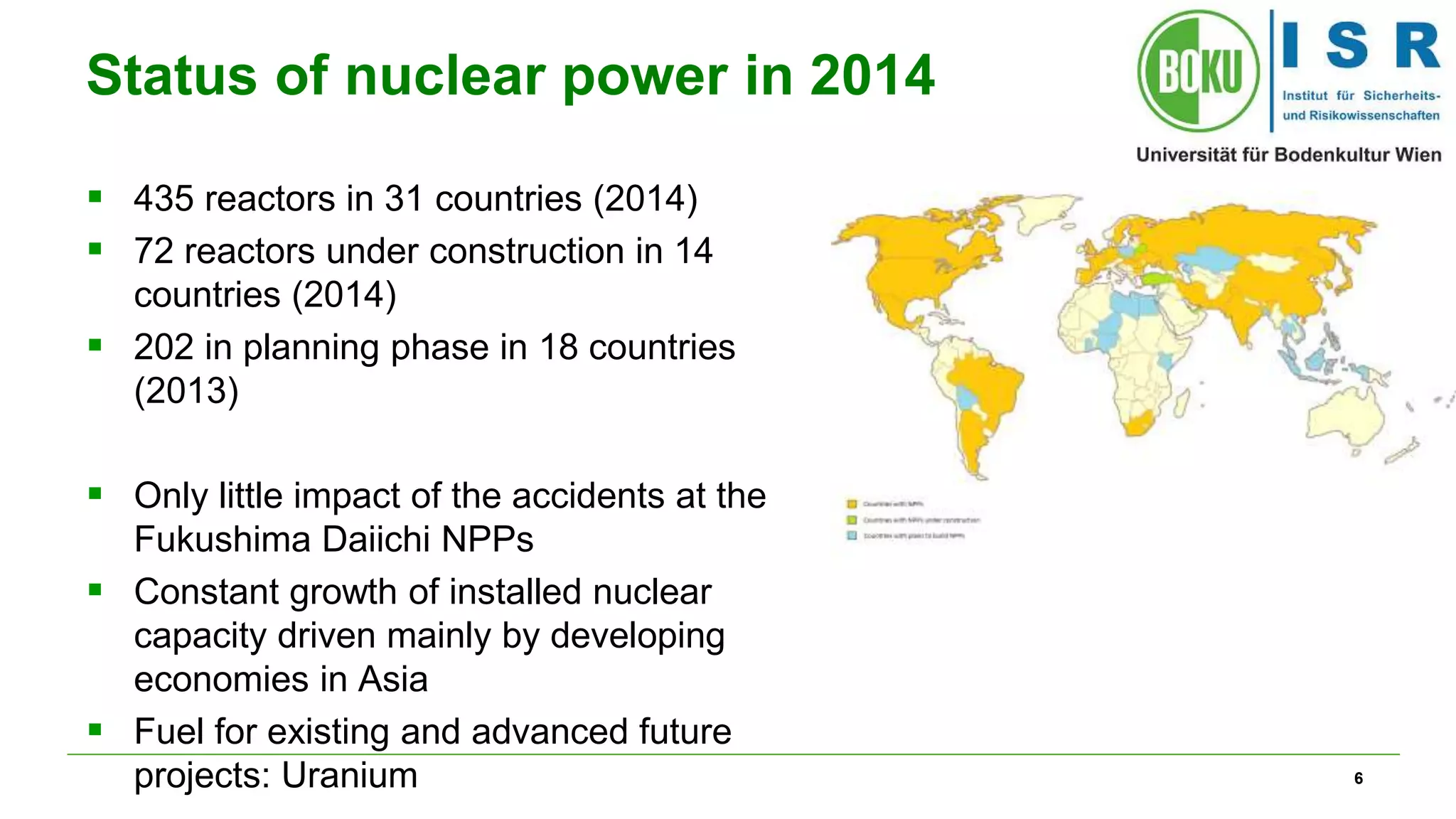

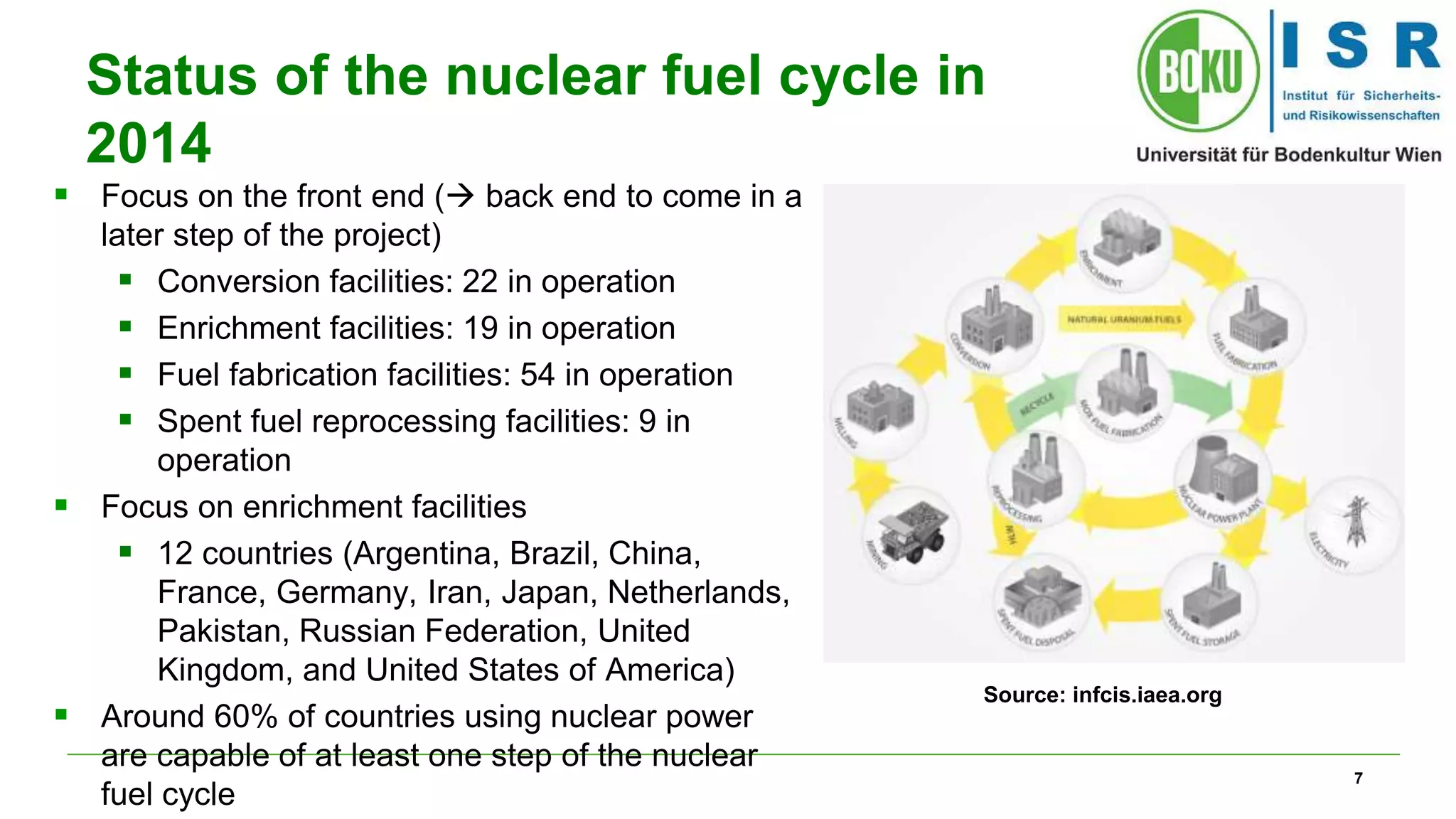

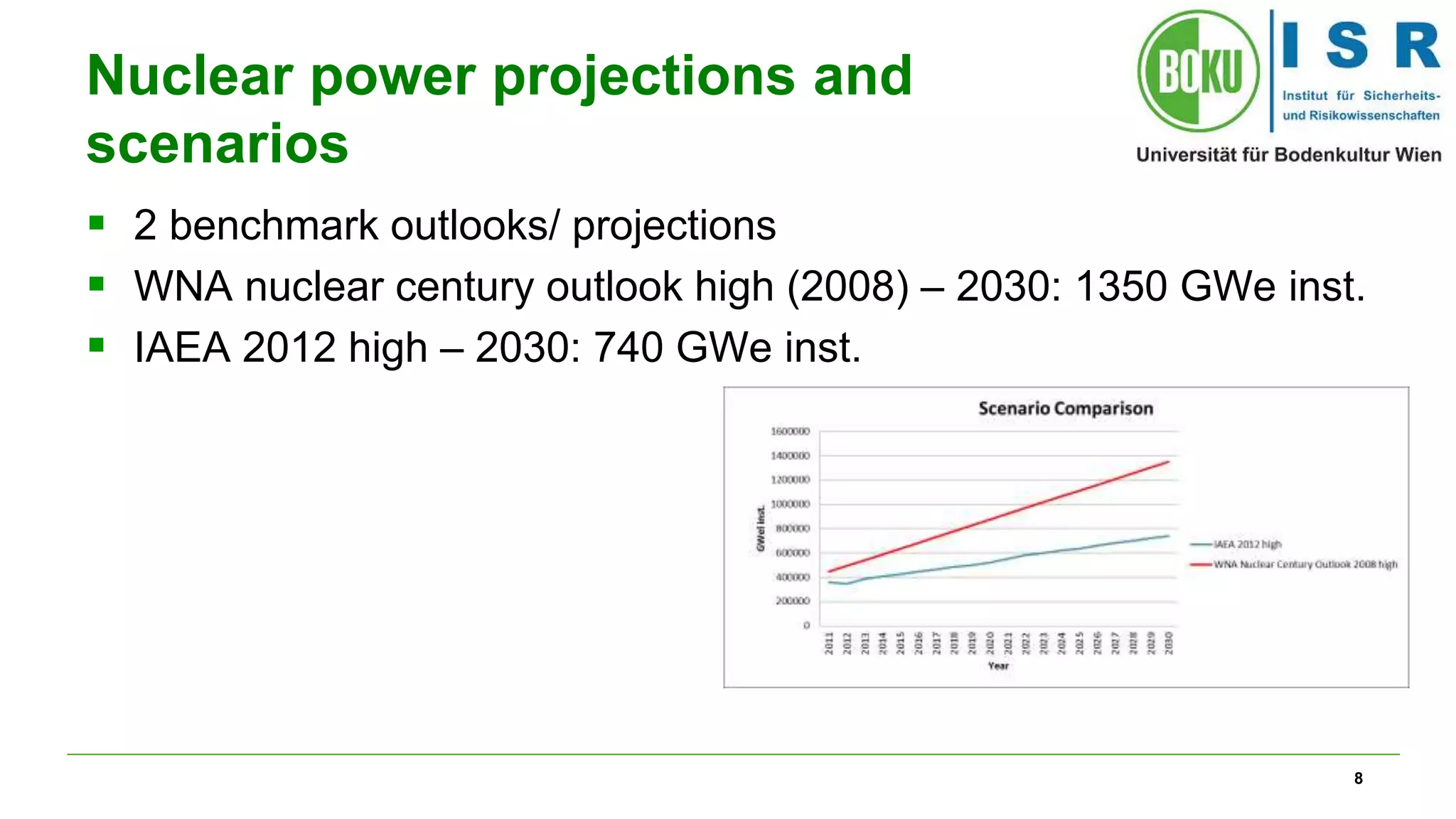

This document discusses emerging proliferation risks associated with potential growth scenarios for nuclear power. It provides background on discussions around nuclear power and climate change. The document analyzes different nuclear power projections and their implications for the nuclear fuel cycle. Meeting higher demand would require expanding uranium enrichment and fuel fabrication facilities globally. This nuclear growth could spread sensitive nuclear technologies and materials, increasing proliferation risks. The document considers potential pathways and their tradeoffs to help ensure fuel supply while limiting risks. More intrinsic proliferation-resistant technologies and strengthened international safeguards may be needed to address emerging risks from an expanding nuclear industry.

![16

References

Ahearne, J.F., 2011. Prospects for nuclear energy. Energy Econ. 33, 572–580. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2010.11.014

Arnold, N., Gufler, K., 2012. Fuel cycle risks imposed by a nuclear growth scenario. 4th Int. Disaster Risk Conf. IDRC Davos 2012.

Arnold, N., Gufler, K., 2014. Nuclear Database. Vienna, Austria.

Arnold, N., Kromp, W., Zittel, W., 2011. Perspektiven nuklearer Energieerzeugung bezüglich ihrer Uran Brennstoffversorgung.

Bari, R., Peterson, P., Therios, I., Whitlock, J., 2009. Proliferation Resistance and Physical Protection - Evaluation Methodology Development and Applications. Brookhaven

National Laboratory, Upton, NY.

Gabriel, S., Baschwitz, A., Mathonnière, G., Fizaine, F., Eleouet, T., 2013. Building future nuclear power fleets: The available uranium resources constraint. Resour. Policy

38, 458–469. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2013.06.008

Gufler, K., 2013. Short and mid-term trends of the development of nuclear energy. ISR, Wien.

IAEA, 2008. Guidance for the Application of an Assessment Methodology for Innovative Nuclear Energy Systems, INPRO Manual — Proliferation Resistance, IAEA-

TECDOC-1575 Rev. 1. Vienna, Austria.

IAEA, 2012. Energy, Electricity and Nuclear Power, Estimates for the Period up to 2050; Reference Data Series No.1, 2012 Edition, IAEA Vienna. Vienna, Austria.

IAEA, 2013. IAEA ministerial conference on nuclear power in the 21th century.

IAEA, 2014a. IAEA PRIS [WWW Document]. URL http://www.iaea.org/pris/home.aspx

IAEA, 2014b. Integrated Nuclear Fuel Cycle Information System [WWW Document].

IAEA, 2014c. IAEA Technical Meeting on topical issues in the development of nuclear power infrastructure.

IEA, 2013. World Energy Outlook 2012. Paris, France.

Kessides, I.N., Wade, D.C., 2011. Towards a sustainable global energy supply infrastructure: Net energy balance and density considerations. Energy Policy 39, 5322–

5334. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2011.05.032

Knapp, V., Pevec, D., Matijević, M., 2010. The potential of fission nuclear power in resolving global climate change under the constraints of nuclear fuel resources and

once-through fuel cycles. Energy Policy, Energy Efficiency Policies and Strategies with regular papers. 38, 6793–6803. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.06.052

WNA, 2008. WNA Nuclear Century Outlook.

Zittel, W., Arnold, N., Liebert, W., 2013. Nuclear Fuel and Availability. Vienna, Ottobrunn, Darmstadt.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/idrc2014emerging-proliferation-update755-140827073551-phpapp02/75/IDRC_2014_emerging-proliferation-update-16-2048.jpg)