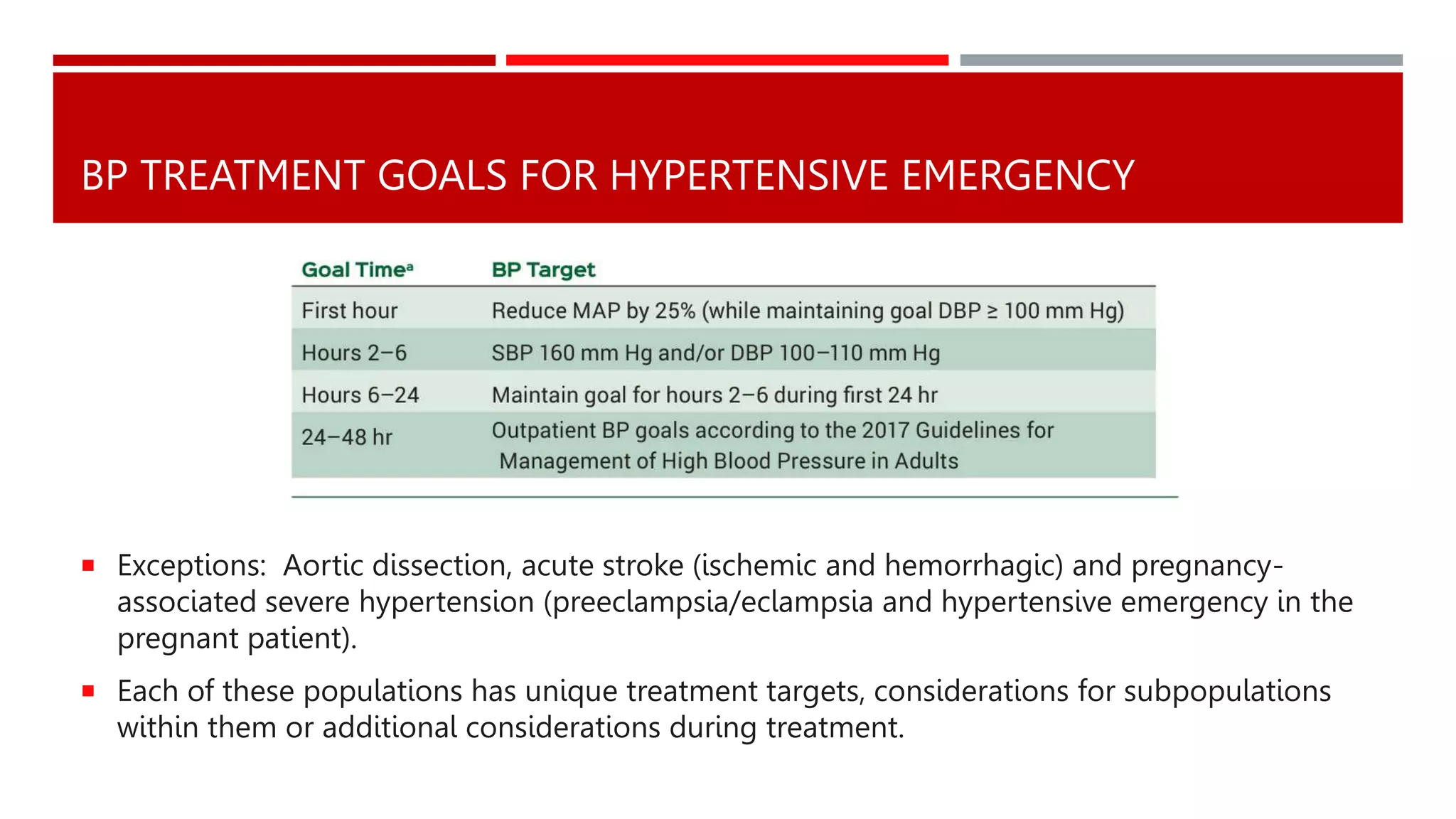

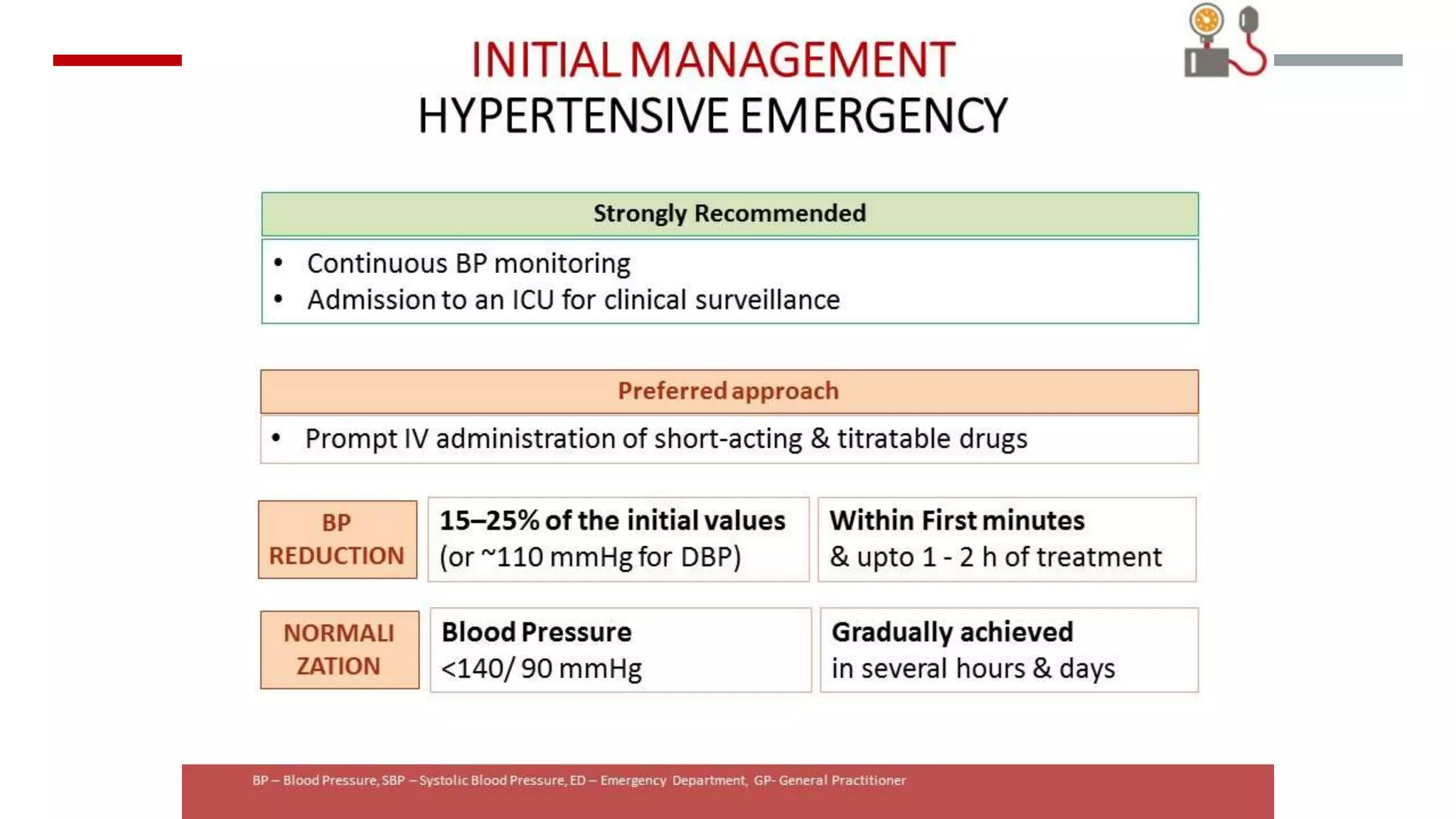

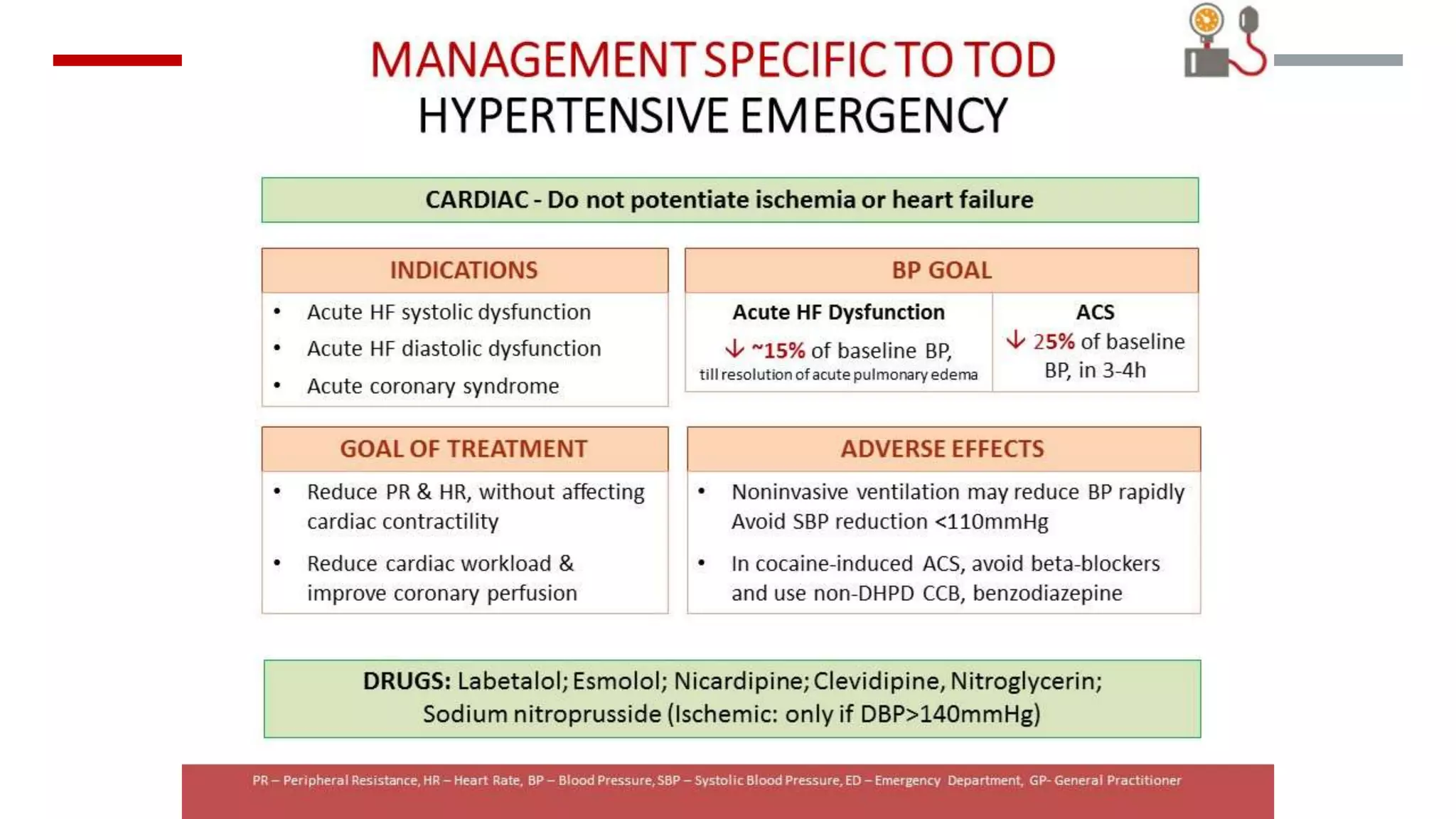

Hypertensive emergencies are defined by severe blood pressure elevations (>180/120 mmHg) with potential organ dysfunction, requiring immediate treatment to prevent complications. Although they are infrequent, hospitalizations for these conditions have risen, with a low in-hospital mortality rate. Effective management hinges on recognizing the distinction between emergencies and urgencies, tailoring therapy accordingly, and ensuring close monitoring to avoid overcorrection.