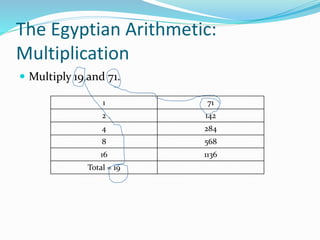

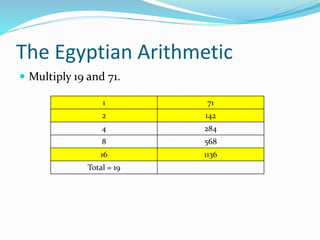

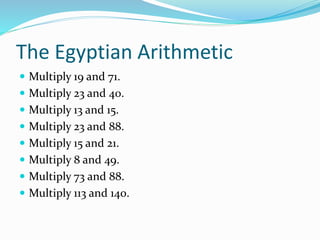

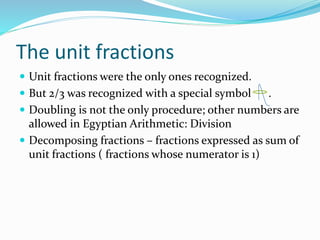

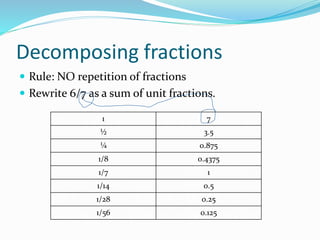

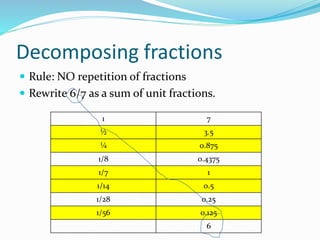

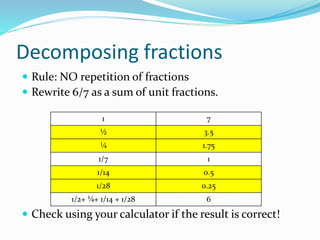

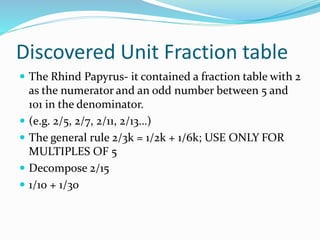

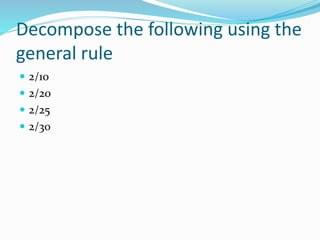

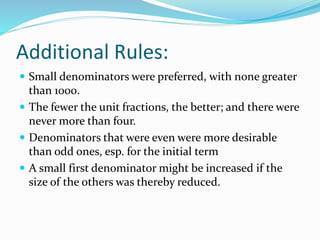

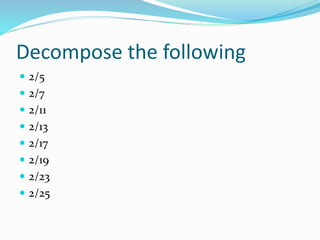

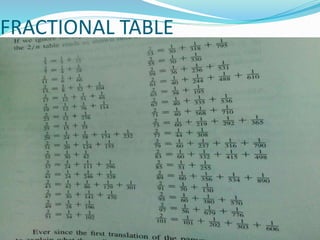

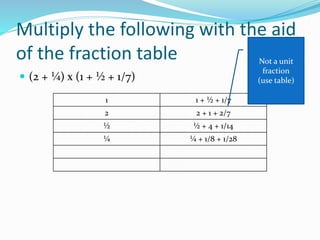

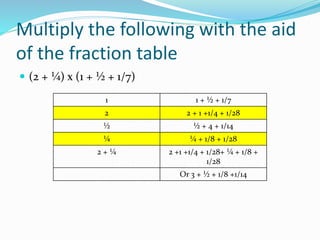

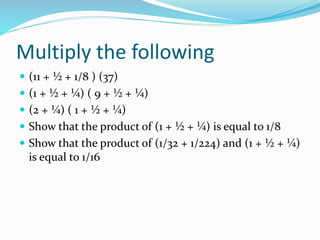

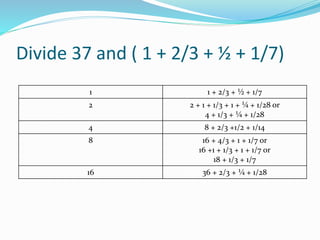

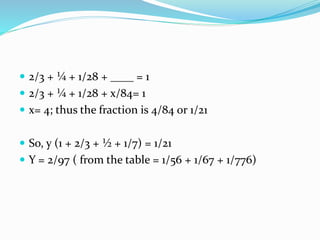

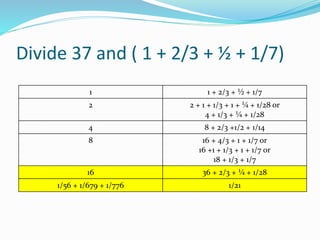

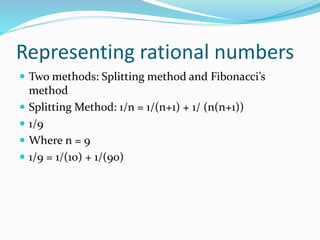

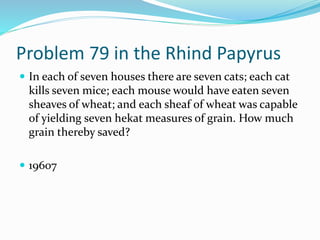

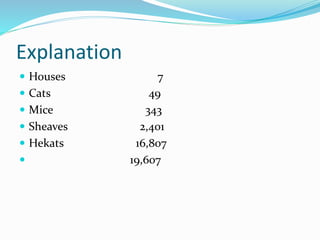

The document discusses Egyptian mathematics as recorded in historical papyri. It describes how the Egyptians developed mathematics out of practical needs like commerce, construction, and taxation of agricultural land. Much of our knowledge comes from the Rhind and Moscow papyri, which contain early examples of arithmetic operations like multiplication and fraction decomposition. The Rosetta Stone later helped decipher Egyptian hieroglyphics. Key figures who advanced the field include Champollion, who established the translation of hieroglyphics, and Rhind and Moscow, after whom the important papyri are named. The document provides several examples of early Egyptian arithmetic techniques.