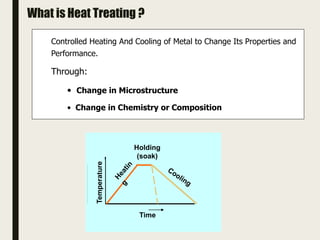

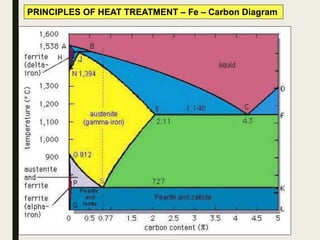

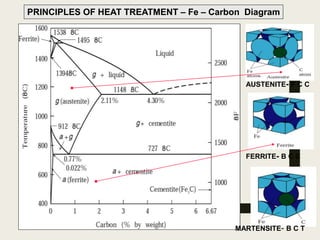

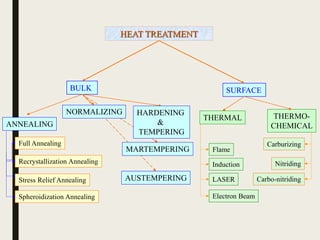

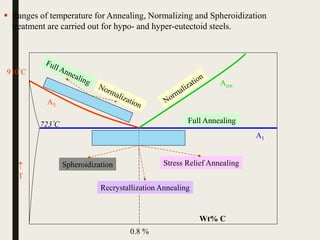

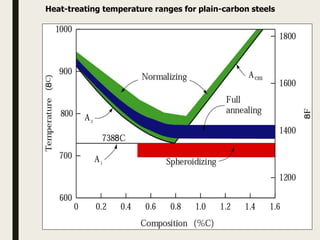

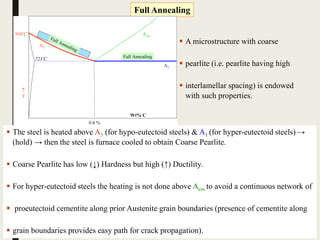

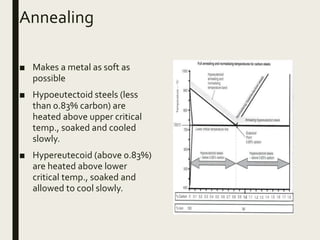

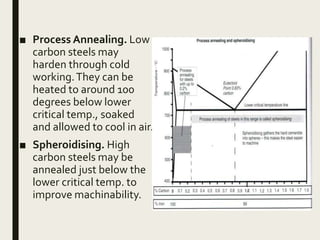

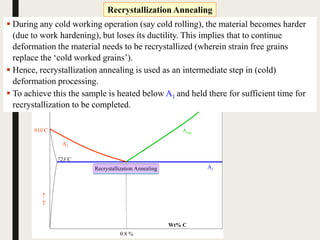

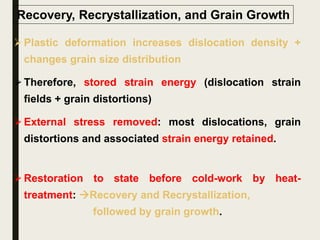

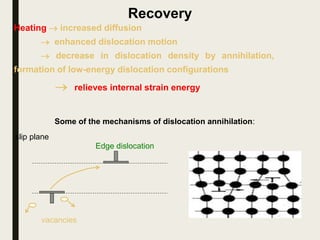

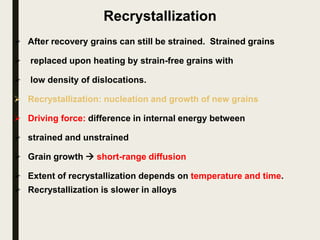

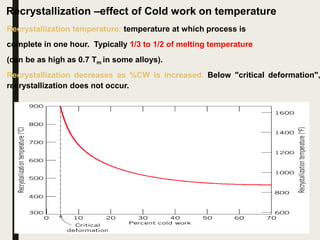

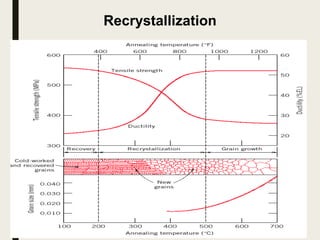

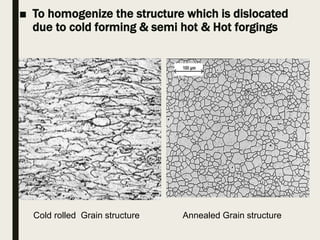

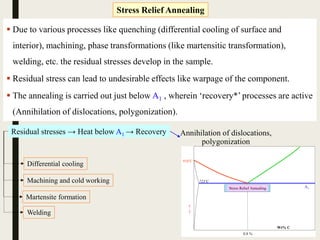

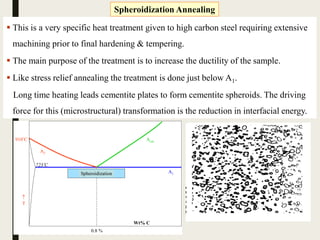

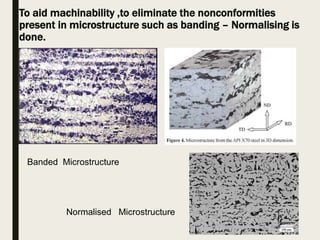

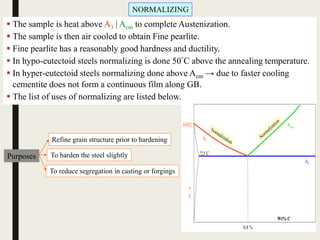

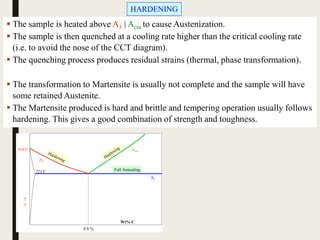

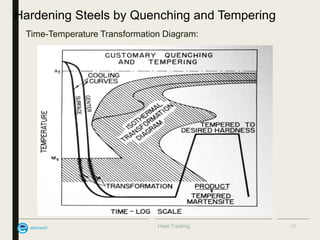

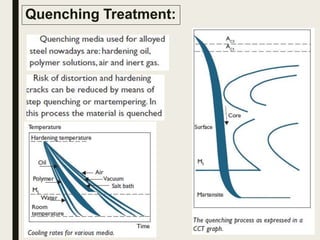

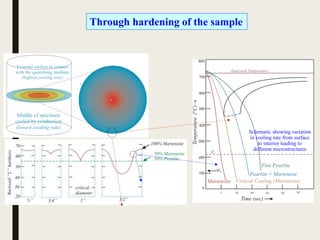

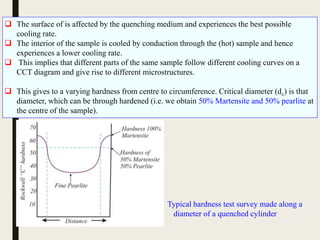

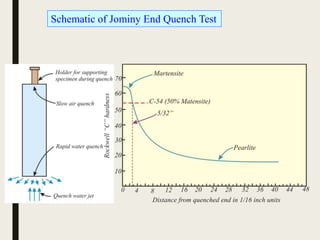

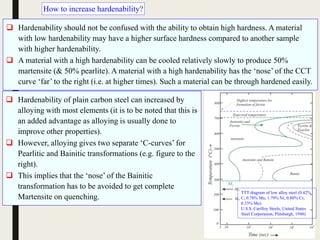

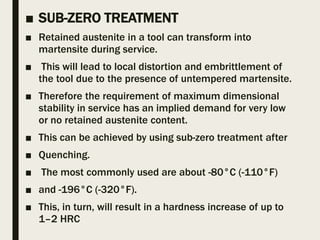

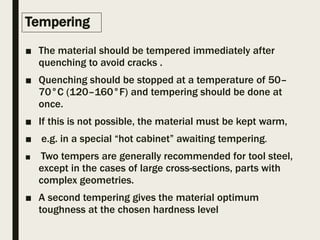

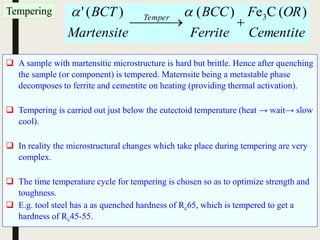

The document provides an overview of heat treatment processes in metallurgy, explaining how controlled heating and cooling affect the properties of metals like toughness, hardness, and ductility. It details various heat treatment methods, including annealing, hardening, and tempering, along with their specific temperature ranges and microstructural transformations. Additionally, it discusses the importance of processes like normalizing and stress relief in enhancing the machinability and overall performance of steel alloys.