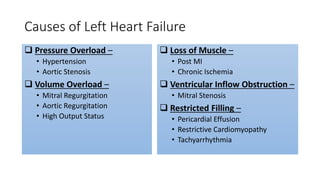

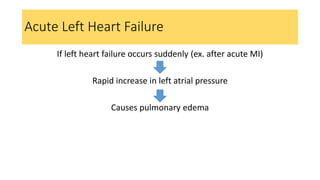

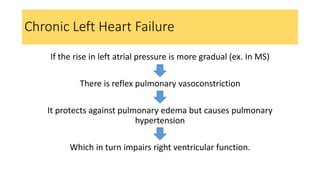

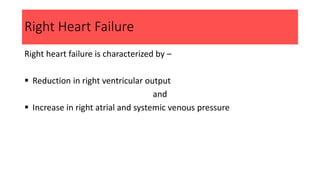

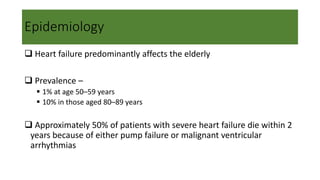

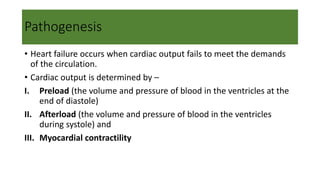

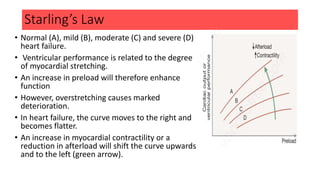

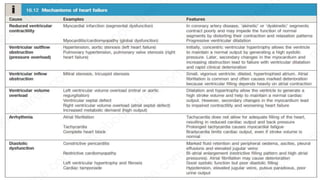

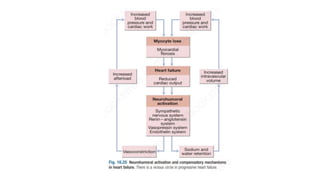

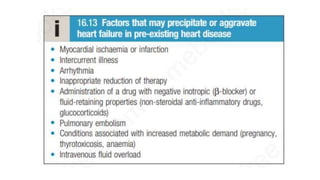

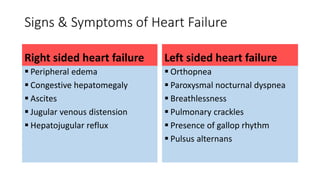

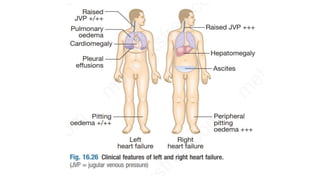

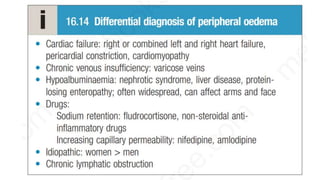

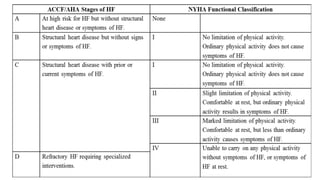

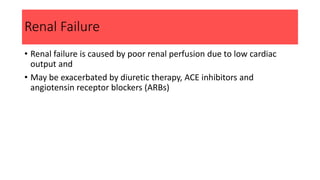

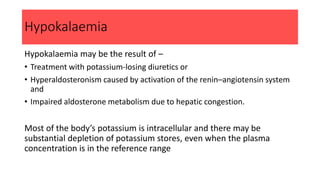

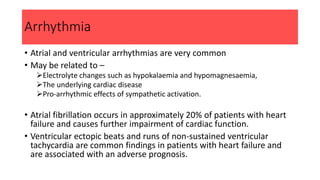

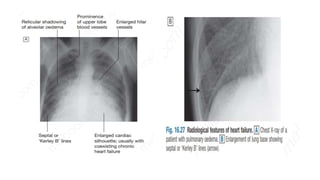

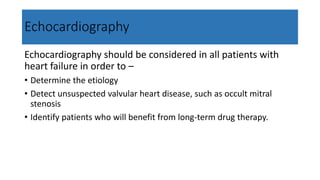

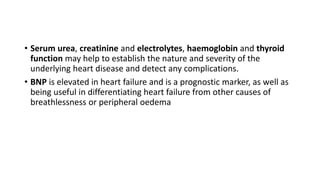

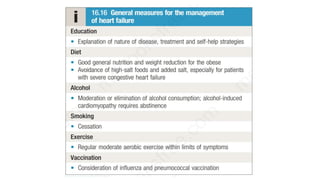

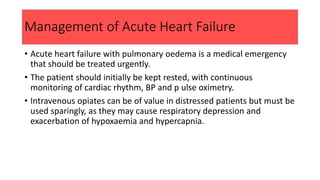

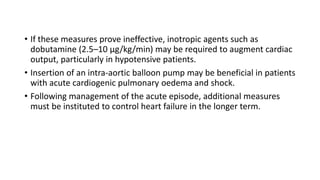

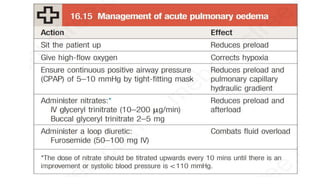

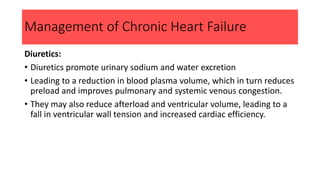

The document provides a comprehensive overview of heart failure, detailing its types (left, right, and biventricular), causes, epidemiology, and pathogenesis. It describes signs, symptoms, complications, investigations, and management strategies for both acute and chronic heart failure, including the roles of various medications and non-pharmacological treatments. The content highlights the importance of monitoring and managing heart failure to improve patient outcomes.