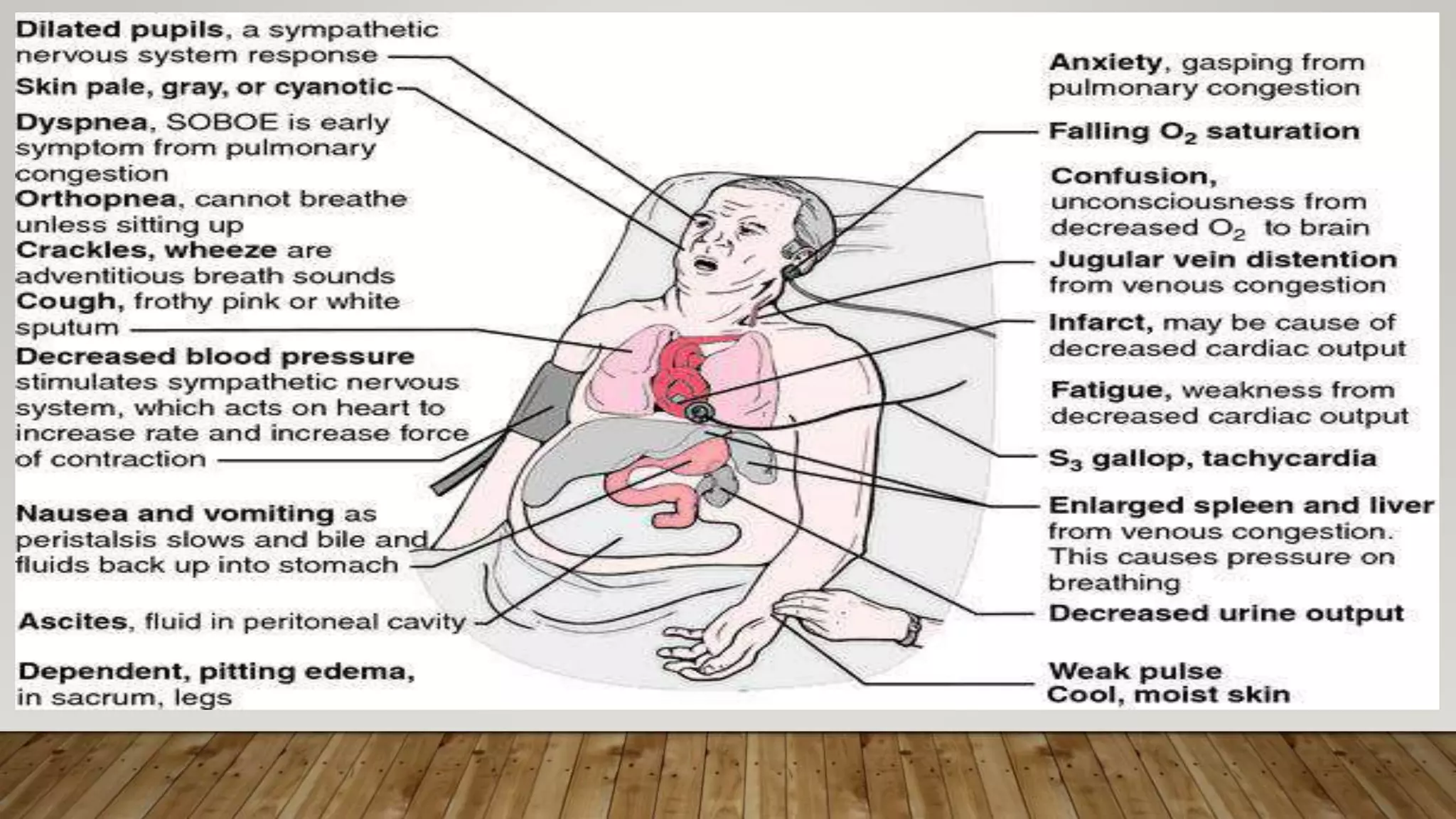

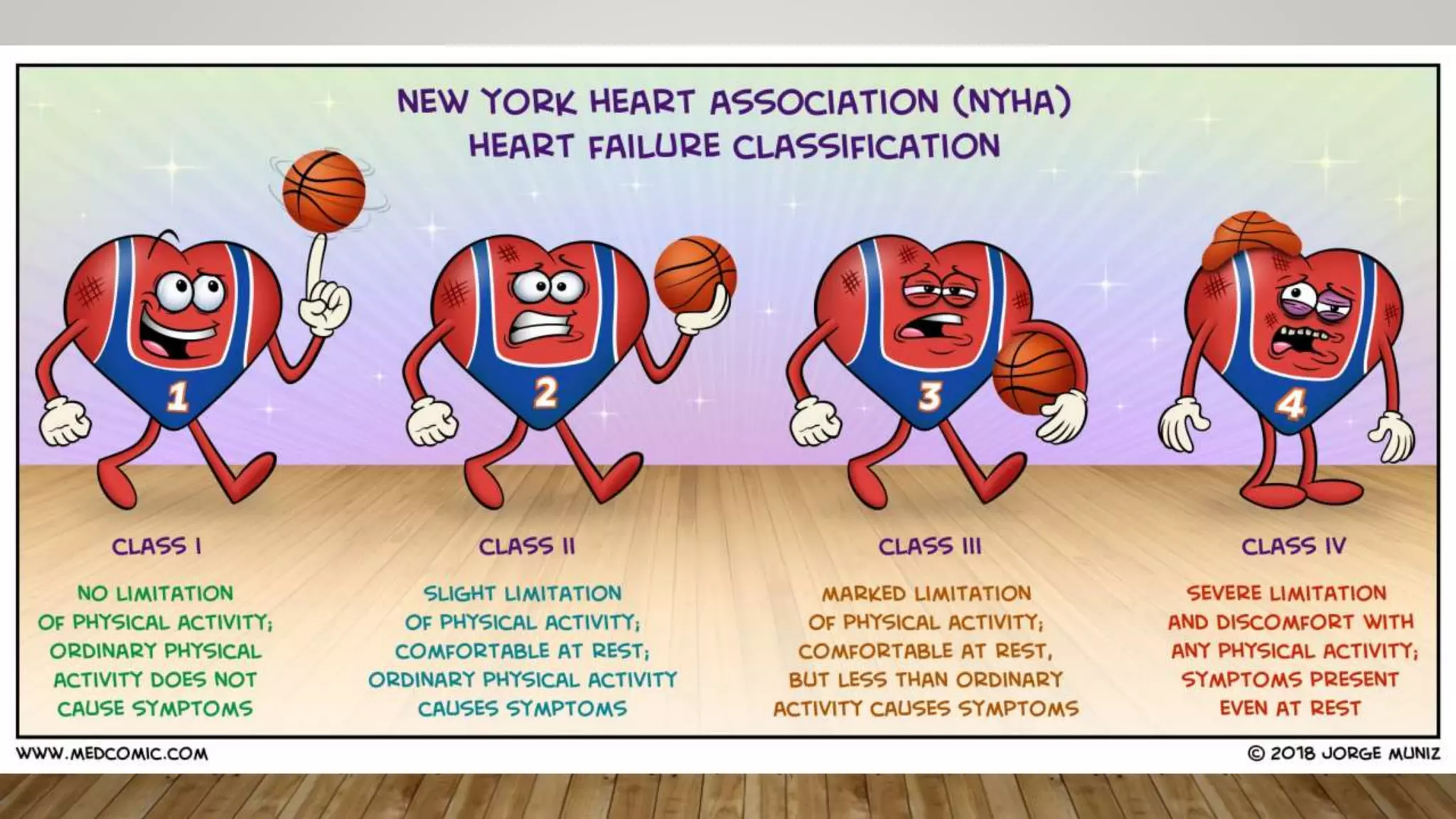

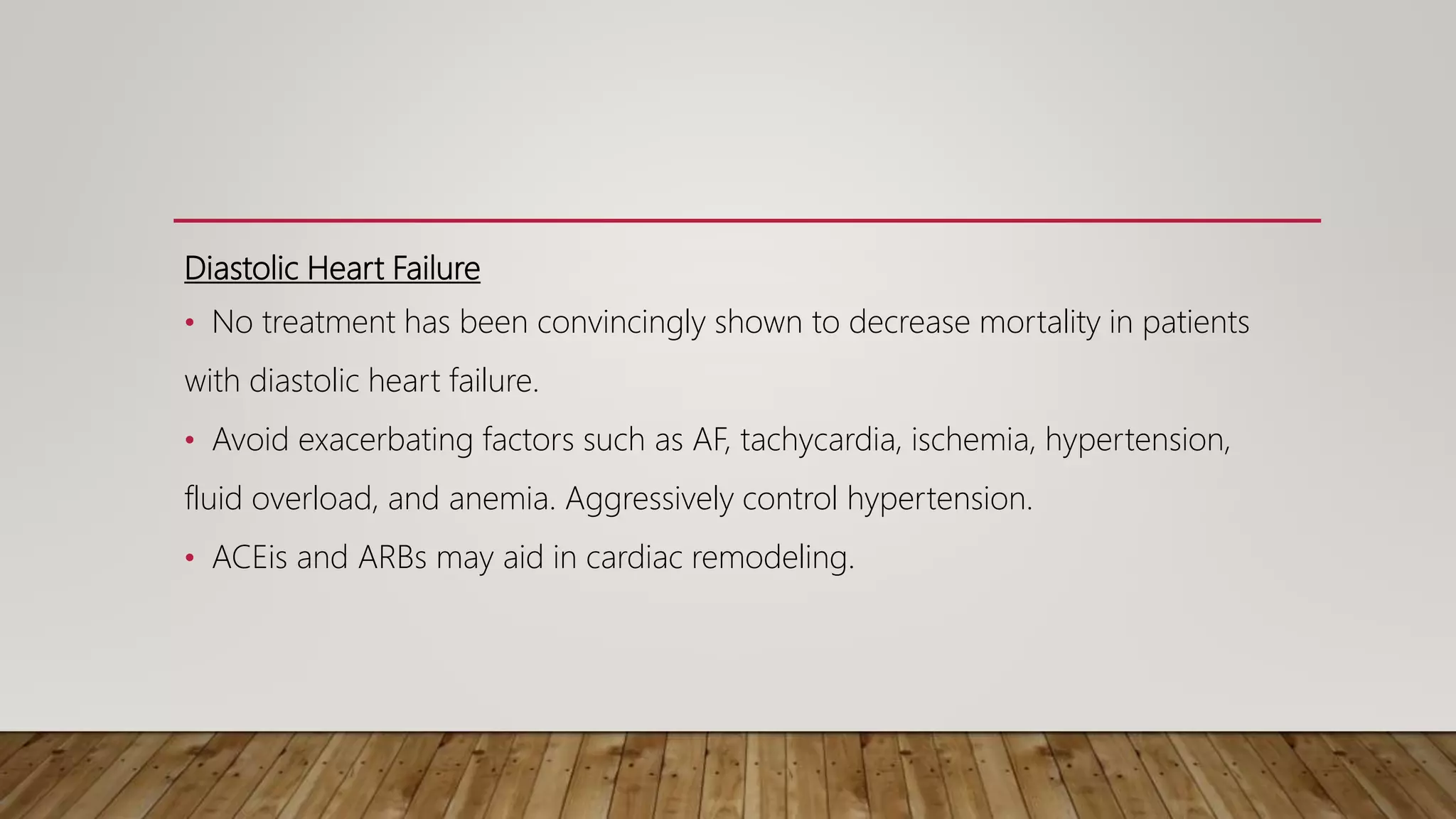

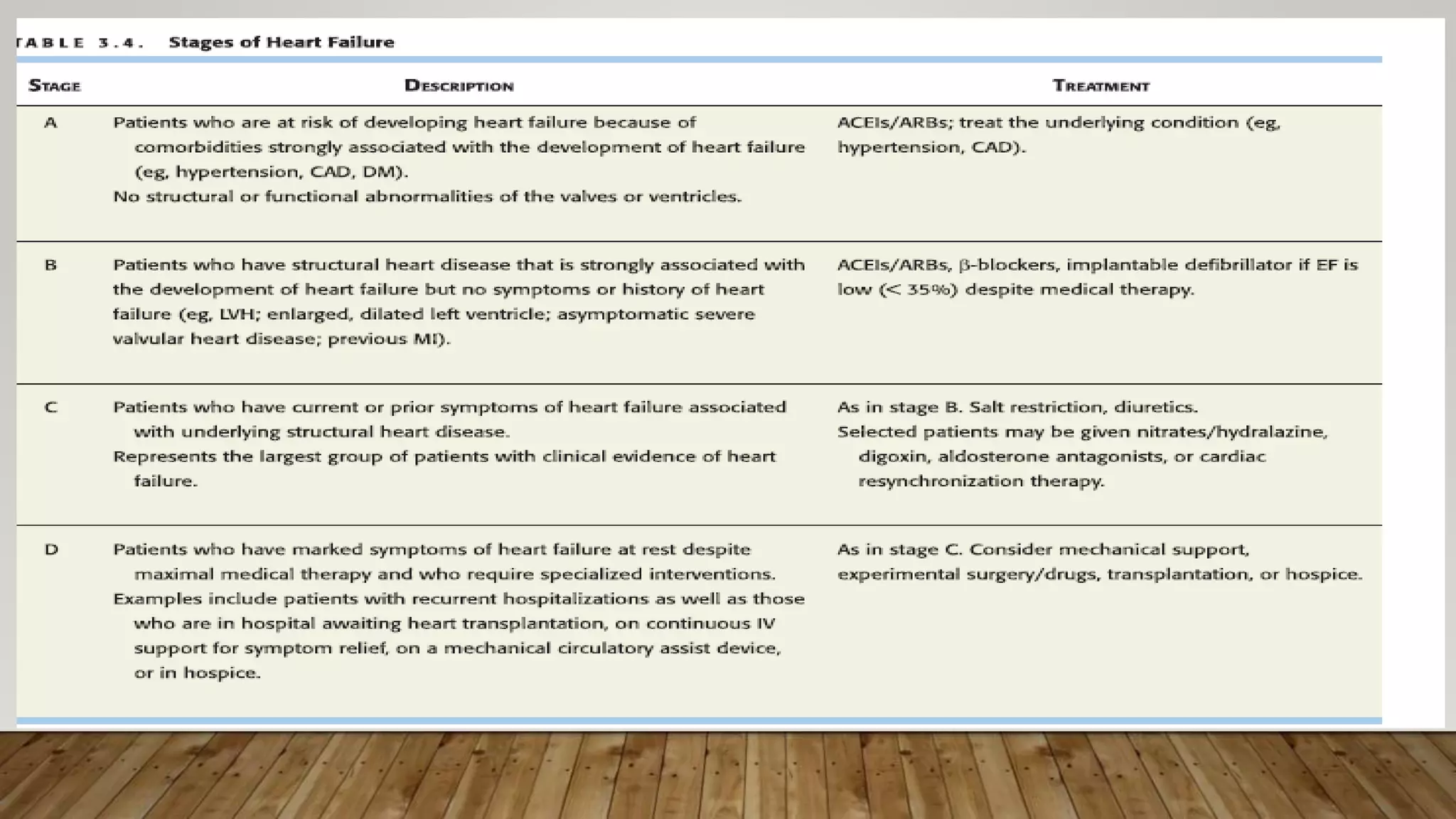

This document discusses heart failure, providing definitions, epidemiology, classifications, etiologies, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Heart failure is defined as a clinical syndrome resulting from structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection of blood. Approximately 2% of developed countries have heart failure, with risk increasing with age. Coronary artery disease is the leading cause. Heart failure can be classified as systolic or diastolic, high-output or low-output, acute or chronic, and right-sided or left-sided. Common causes include coronary artery disease, hypertension, cardiomyopathy, and valvular disease. Treatment involves removing precipitating causes, correcting underlying causes, preventing cardiac