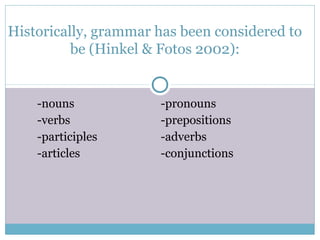

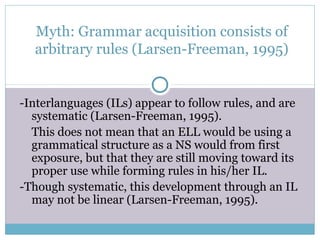

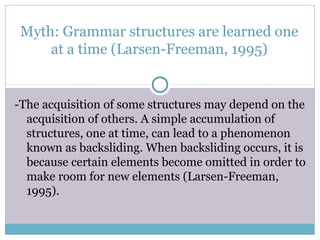

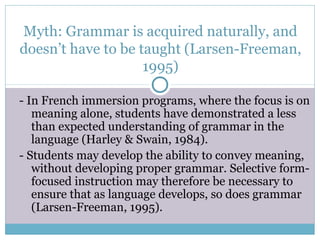

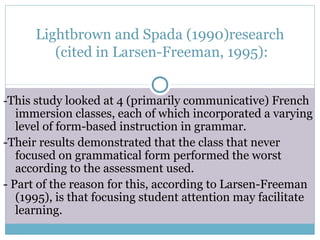

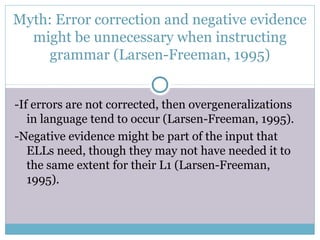

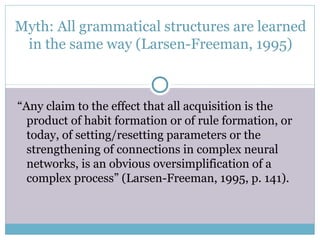

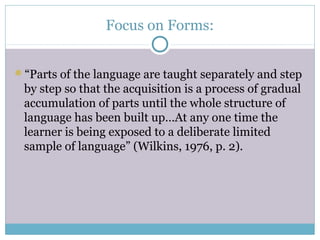

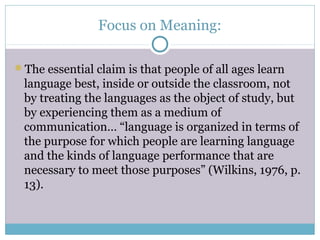

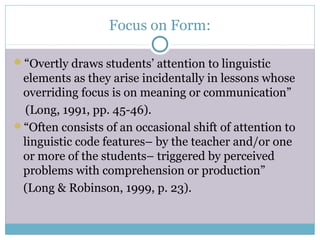

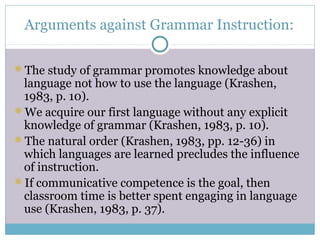

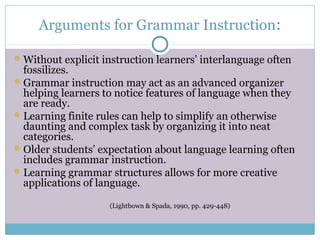

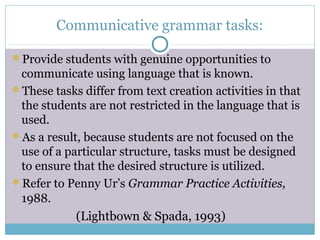

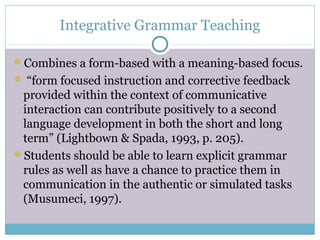

This document discusses various techniques for teaching grammar to English language learners. It describes the historical view of grammar as consisting of parts of speech like nouns and verbs. It also outlines different approaches to grammar instruction, such as direct, functional, and communicative methods. Finally, it debunks several myths about grammar acquisition and argues that grammar is best taught through a focus on form within meaningful communicative activities.