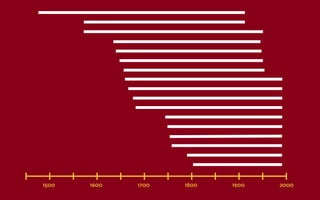

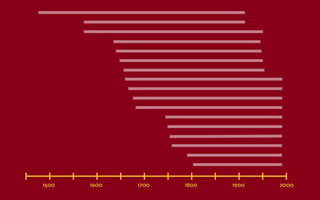

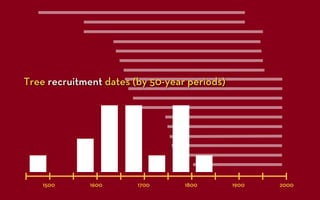

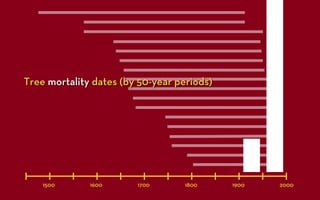

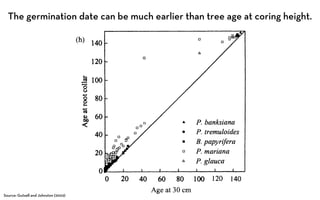

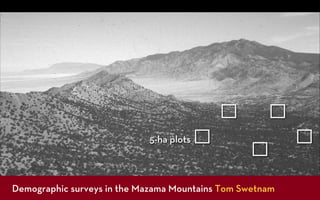

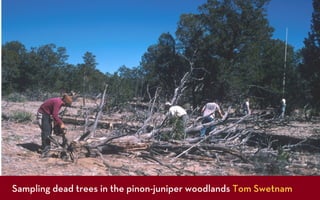

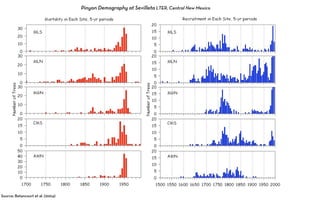

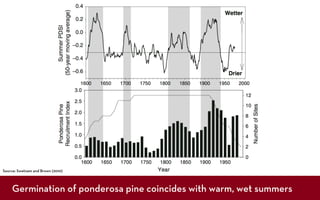

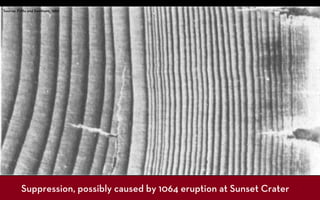

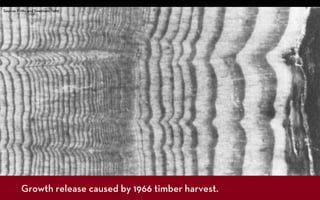

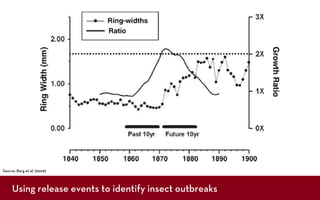

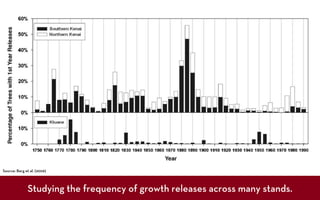

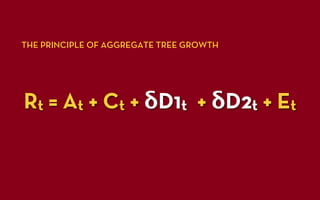

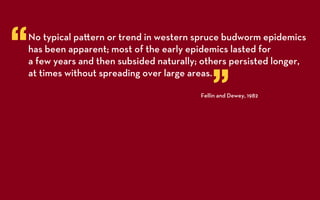

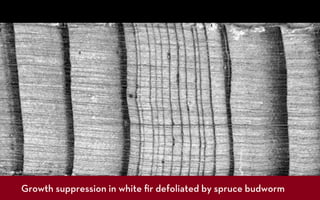

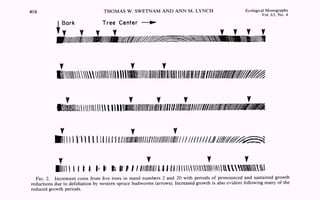

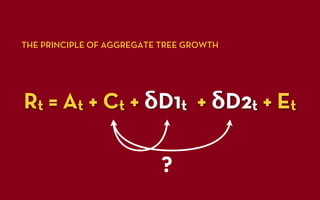

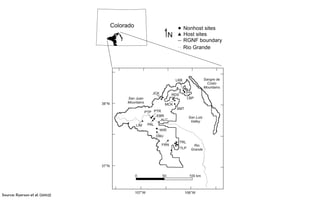

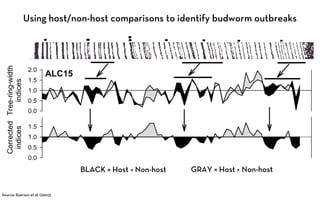

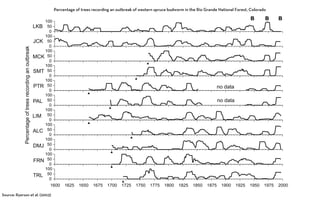

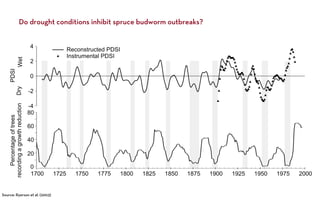

Dendroecology is the use of tree-ring dating and analyses to investigate events and processes involving the interactions of organisms with their environment. It provides a longer temporal perspective than other records through tree-ring evidence that has high precision. Chronological control allows comparison of multiple lines of evidence. However, tree-ring records can be irregular and some processes may be unknown. Past conditions may have no modern analog, complicating interpretation. Dendroecology is used to study forest demography, growth dynamics, and disturbance ecology like insect outbreaks and fire history.