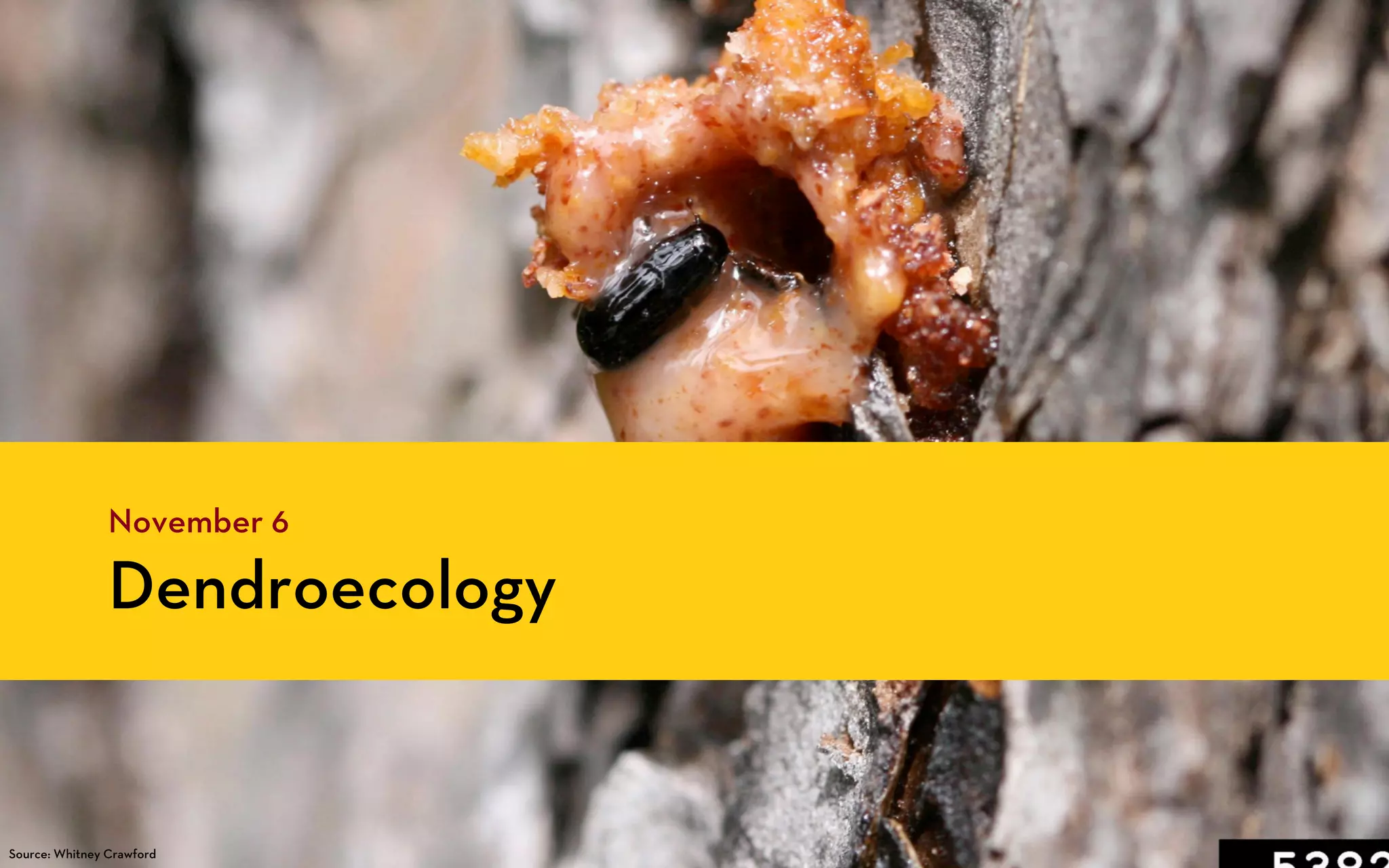

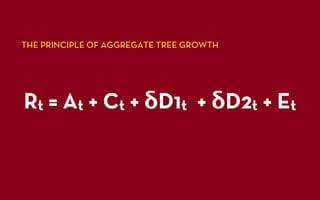

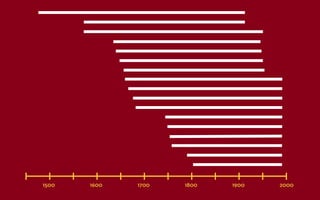

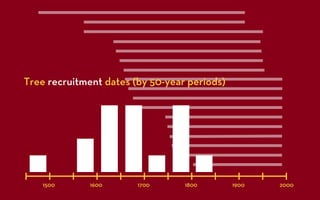

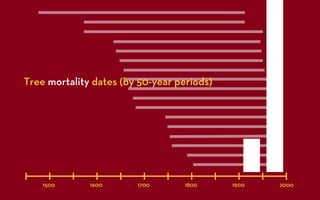

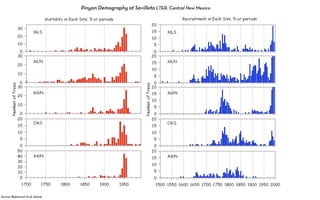

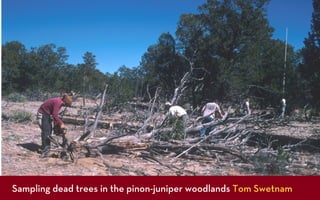

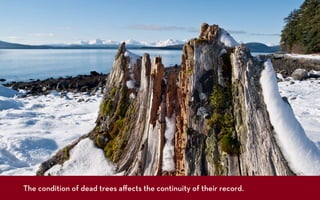

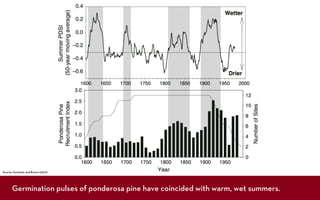

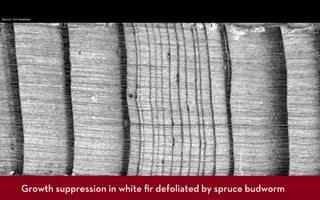

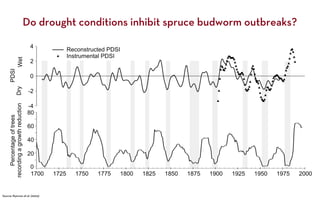

Dendroecology is the study of tree rings to analyze interactions between trees and their environment over time. It provides long-term perspectives on ecosystem processes and dynamics that are difficult to observe directly. Reconstructing forest demography, growth patterns, and disturbance history from tree rings helps understand how climate affects ecosystems. However, tree-ring data have limitations like missing or fragmentary records, and past conditions may differ from present ones.