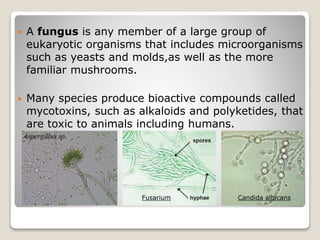

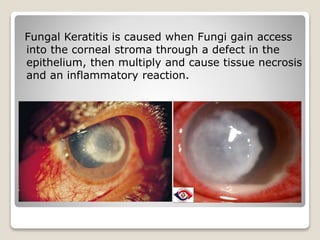

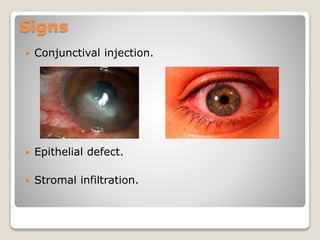

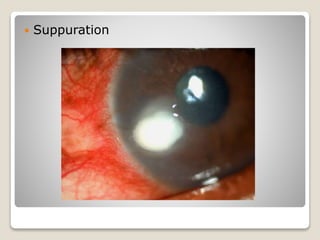

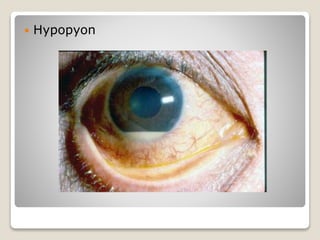

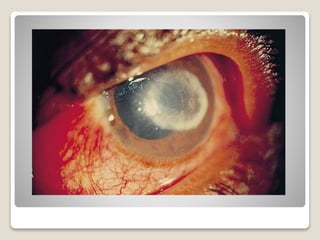

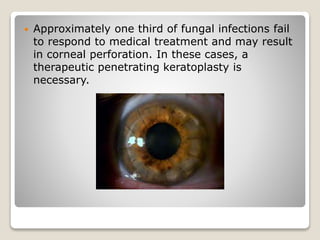

Fungal keratitis is a fungal infection of the cornea that is usually caused by Aspergillus, Fusarium, or Candida albicans fungi. It occurs when fungi enter through a defect in the corneal epithelium and multiply, causing tissue death and inflammation. Risk factors include eye trauma, contact lens use, corneal surgery, and agricultural work. Patients experience eye pain, blurred vision, redness, and discharge. Signs include corneal infiltrates and inflammation. Diagnosis involves corneal scrapings cultured on agar plates. Treatment consists of topical antifungal medications like natamycin, amphotericin B, and azoles. Surgery may be needed for non-responsive cases or corneal perforation