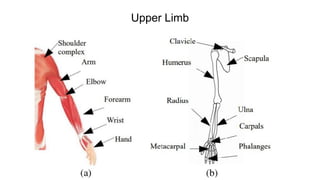

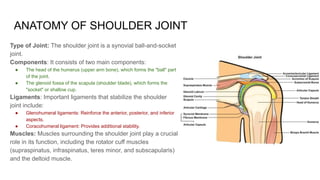

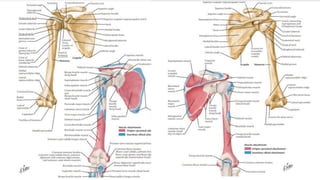

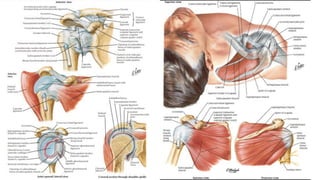

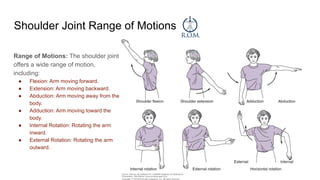

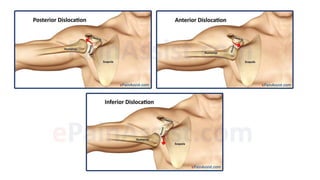

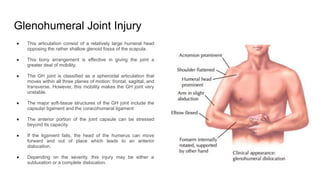

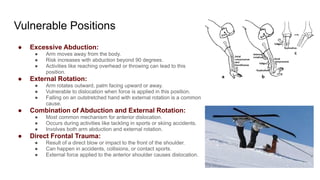

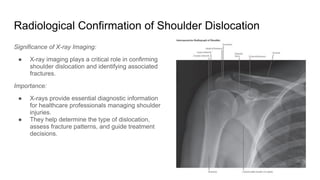

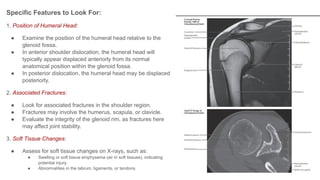

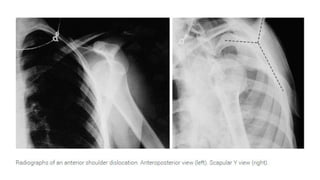

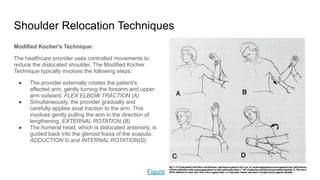

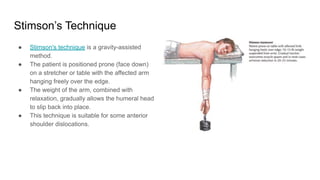

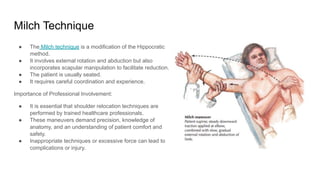

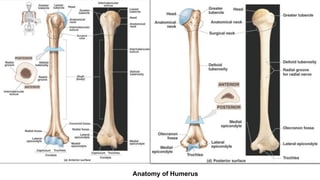

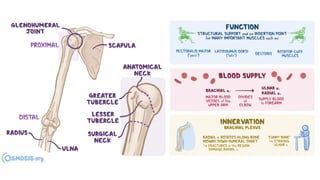

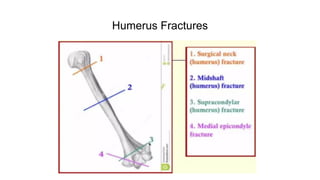

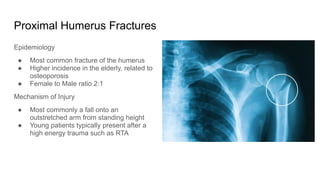

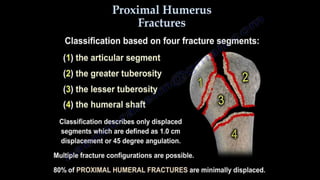

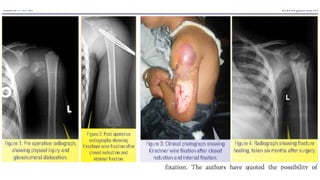

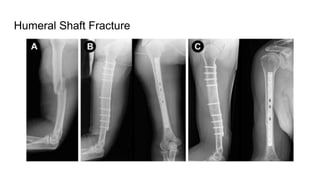

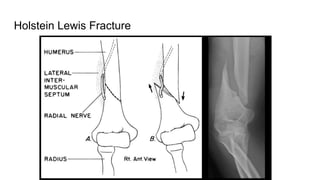

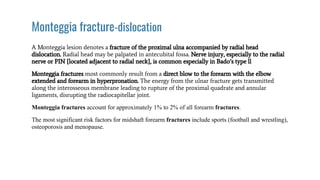

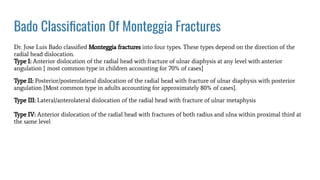

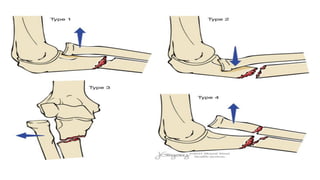

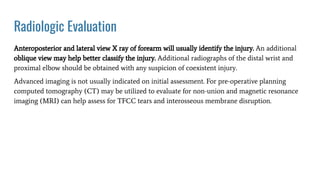

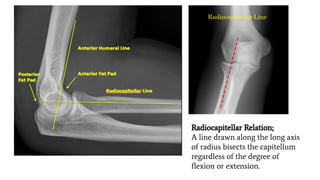

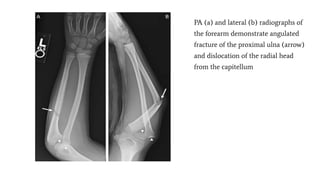

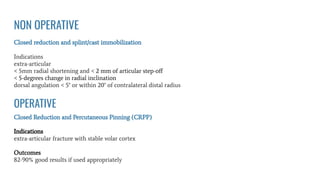

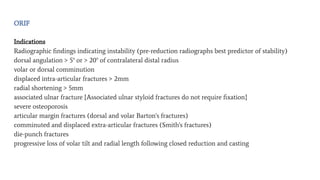

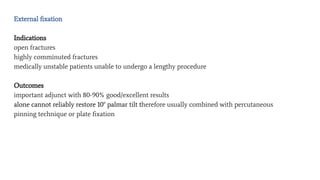

The document covers various aspects of upper limb fractures, including shoulder joint anatomy, common types of shoulder dislocations, and fracture management strategies. It highlights specific injuries such as proximal humerus, Monteggia, and Galeazzi fractures, detailing clinical presentations, mechanisms of injury, and treatment approaches. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of follow-up care and rehabilitation in ensuring proper recovery.