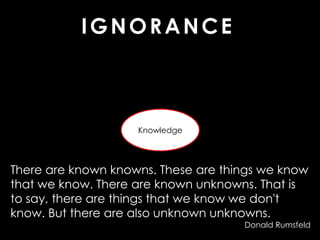

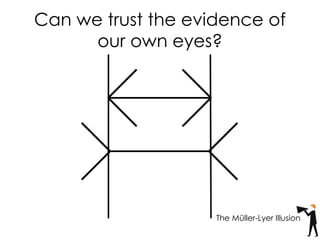

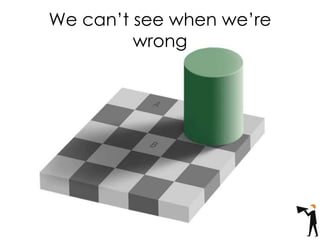

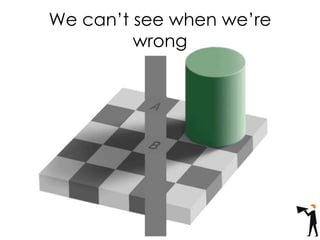

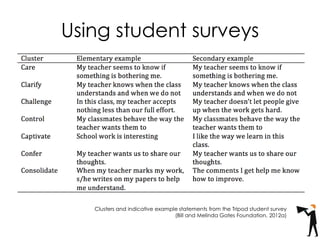

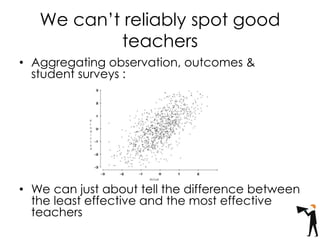

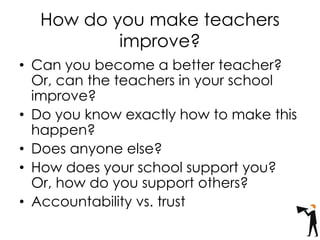

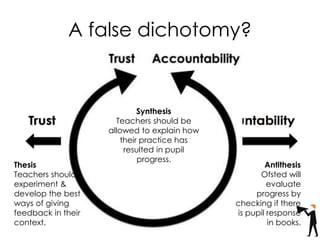

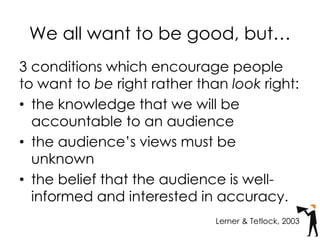

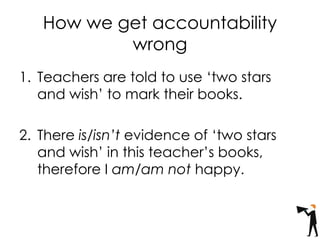

This document summarizes key points from a presentation by David Didau on embracing ignorance and uncertainty in teaching. It discusses that while knowledge is increasing, the gap between what we know and don't know may be widening. It also examines different types of known and unknown knowledge. The document then discusses challenges with evaluating teachers based on observations, student outcomes, and surveys. It argues that accountability should focus on teacher growth, not judgments, and that trusting teachers to improve in their own contexts leads to better outcomes than rigid policies. Overall, the document advocates acknowledging uncertainty and creating conditions where teachers feel supported rather than judged.