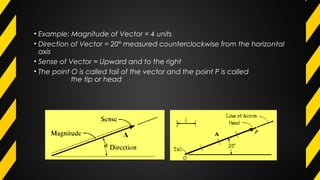

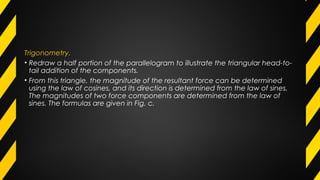

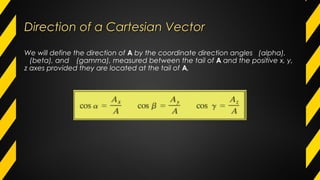

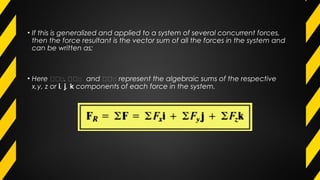

The document provides an overview of force vectors, objectives for understanding vector addition and resolution, and mechanics divided into statics and dynamics. It explains scalar and vector quantities, vector operations, and how to use the parallelogram law for adding forces. Additionally, it discusses analysis procedures, the use of Cartesian vectors for simplifying calculations, and the fundamental concepts of kinematics and kinetics in mechanics.