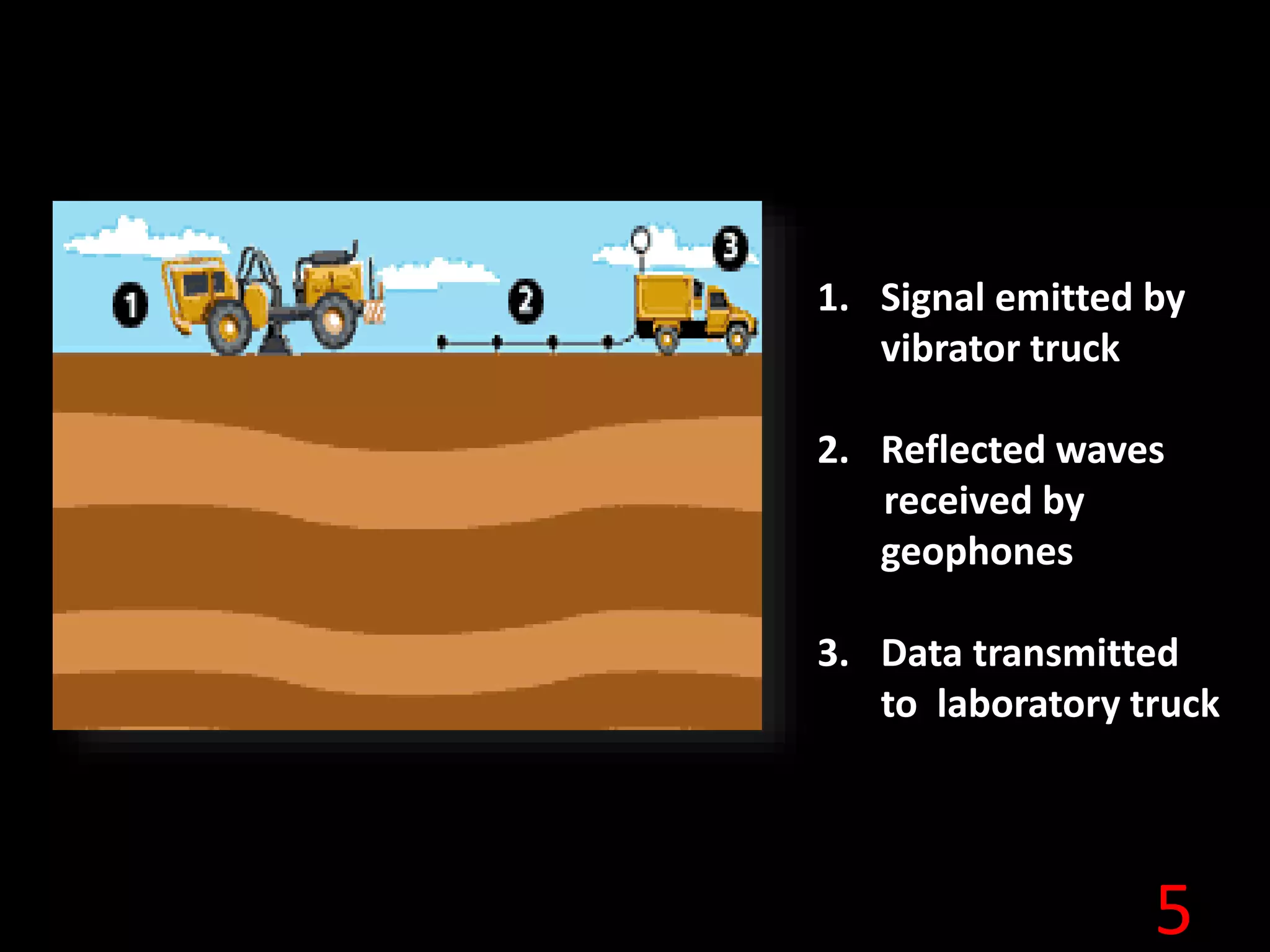

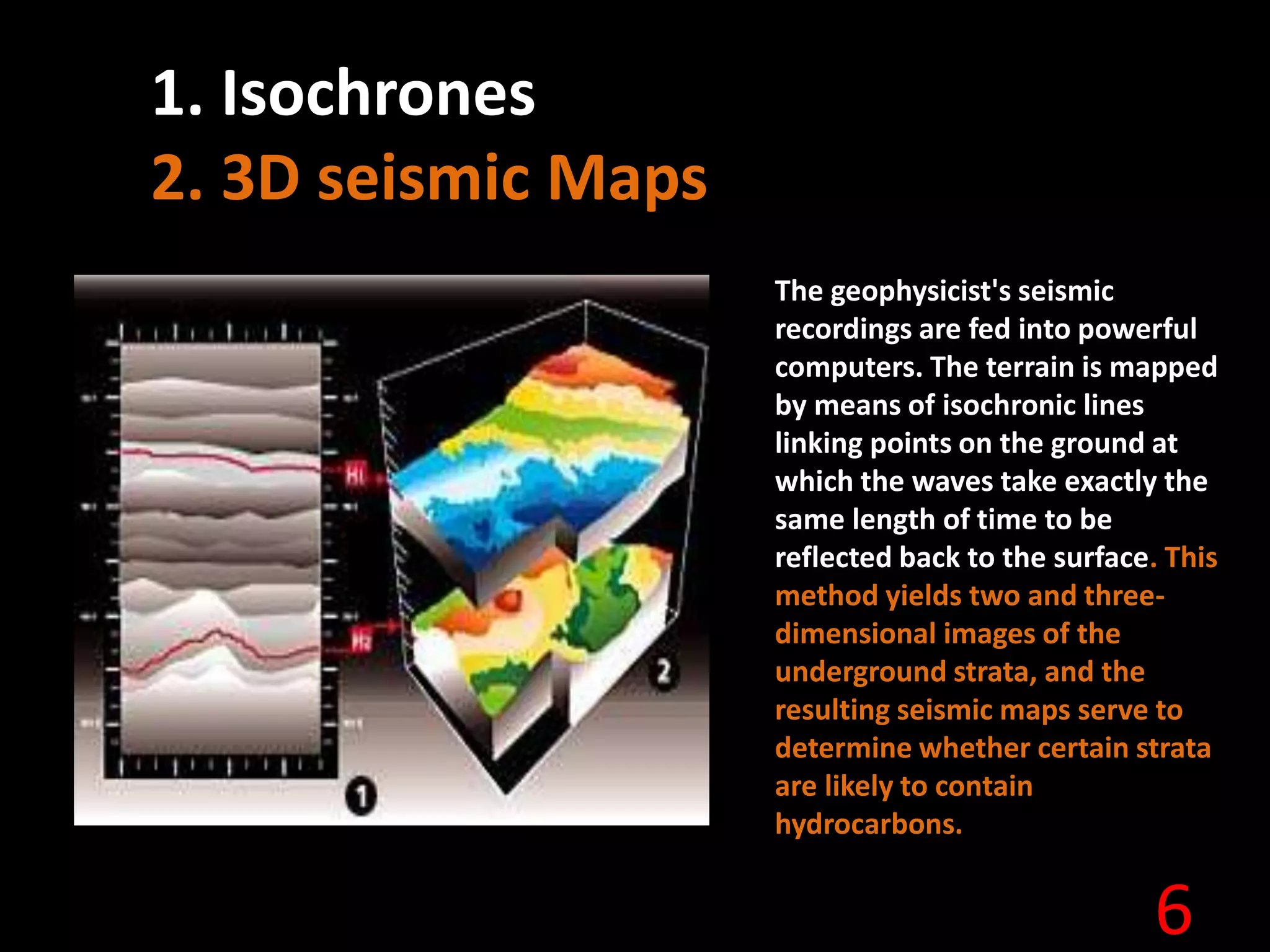

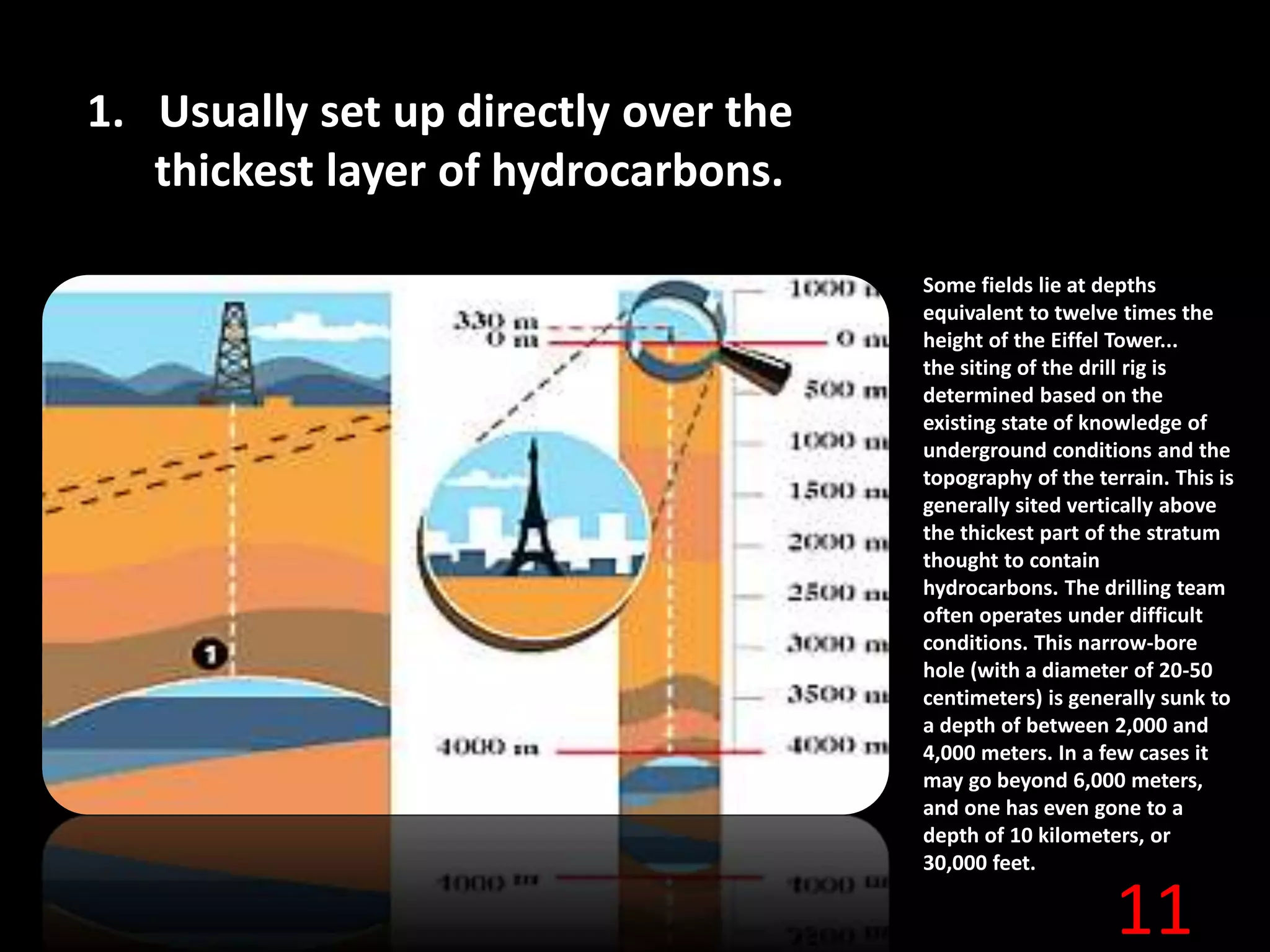

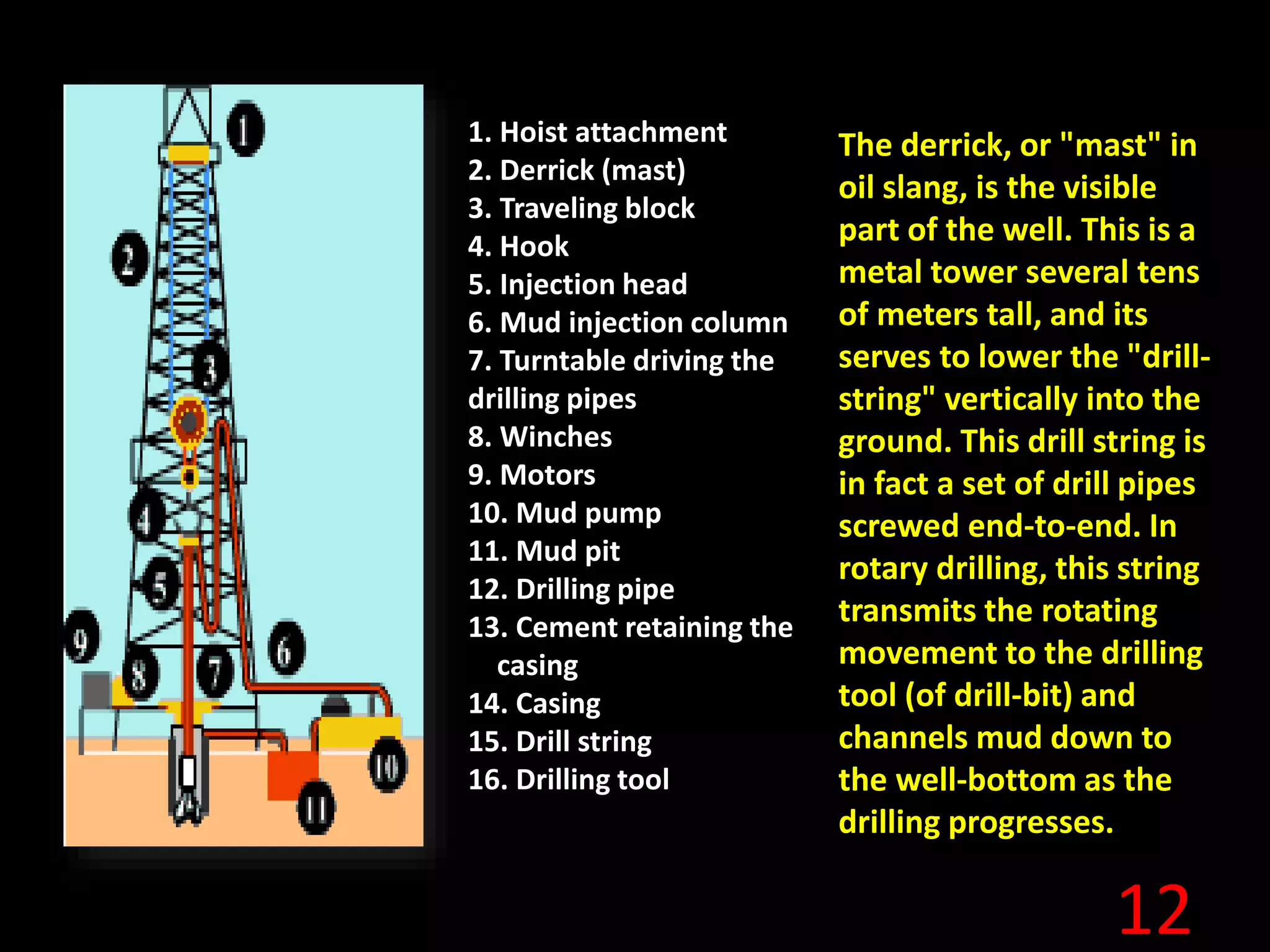

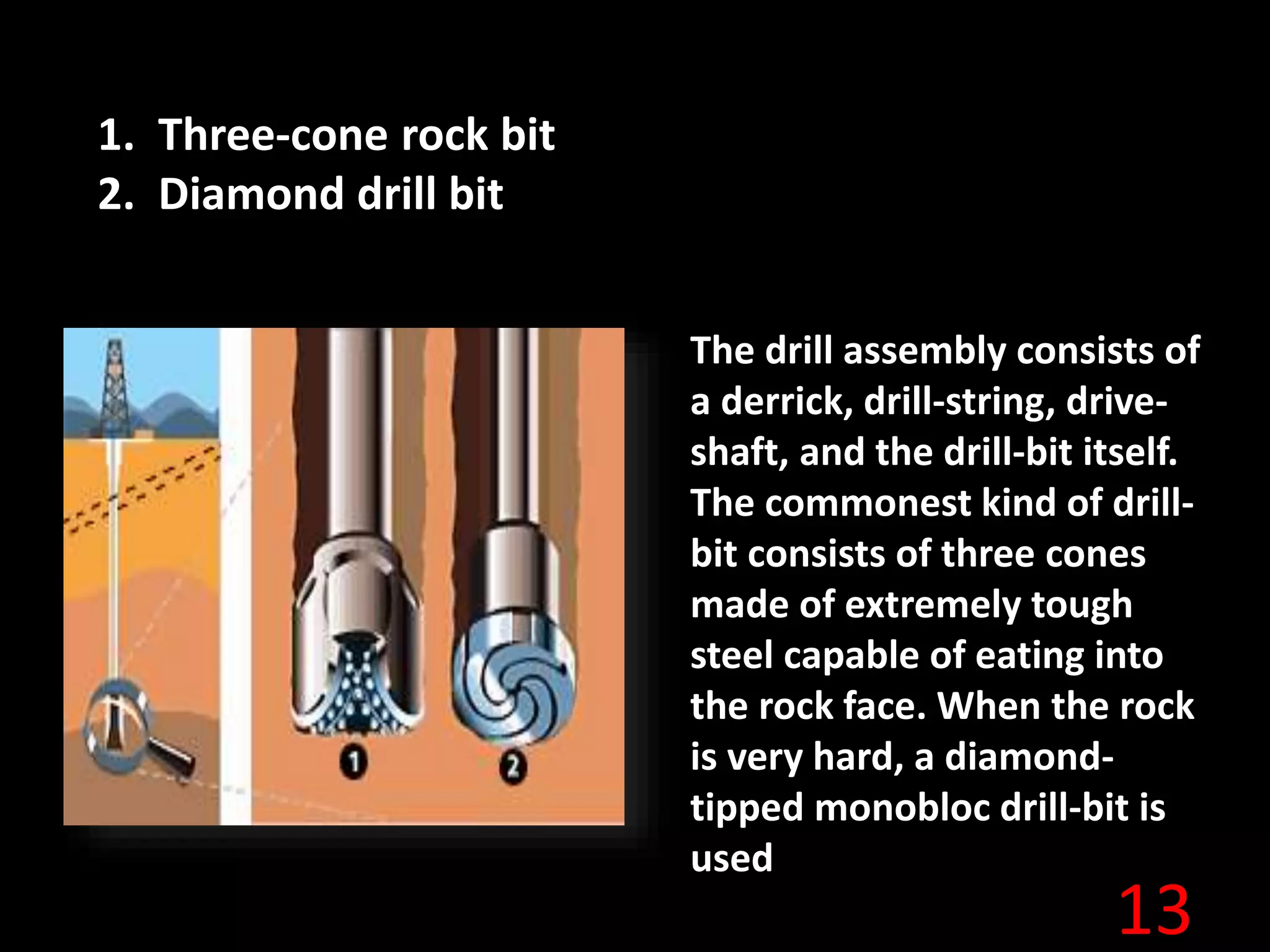

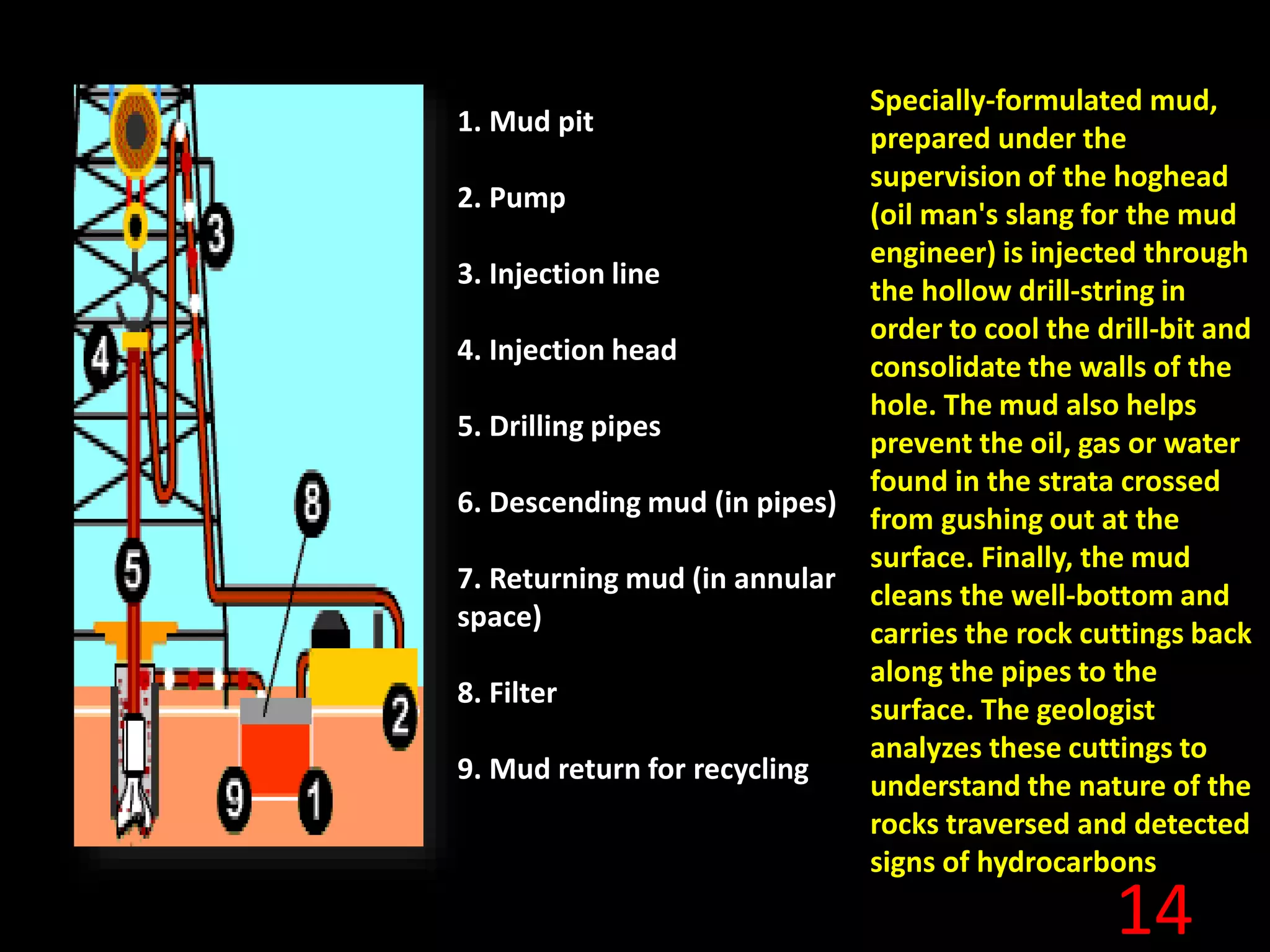

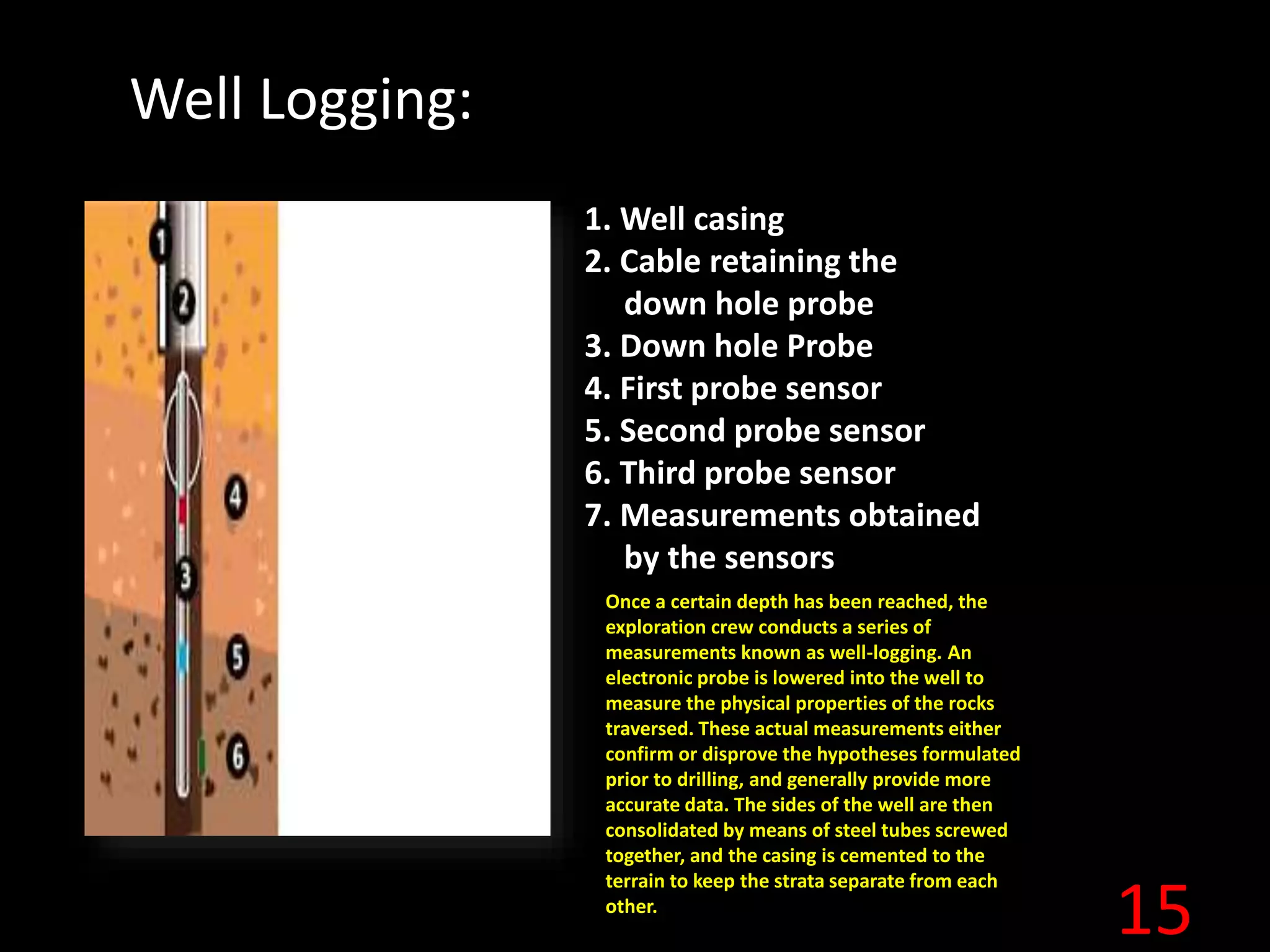

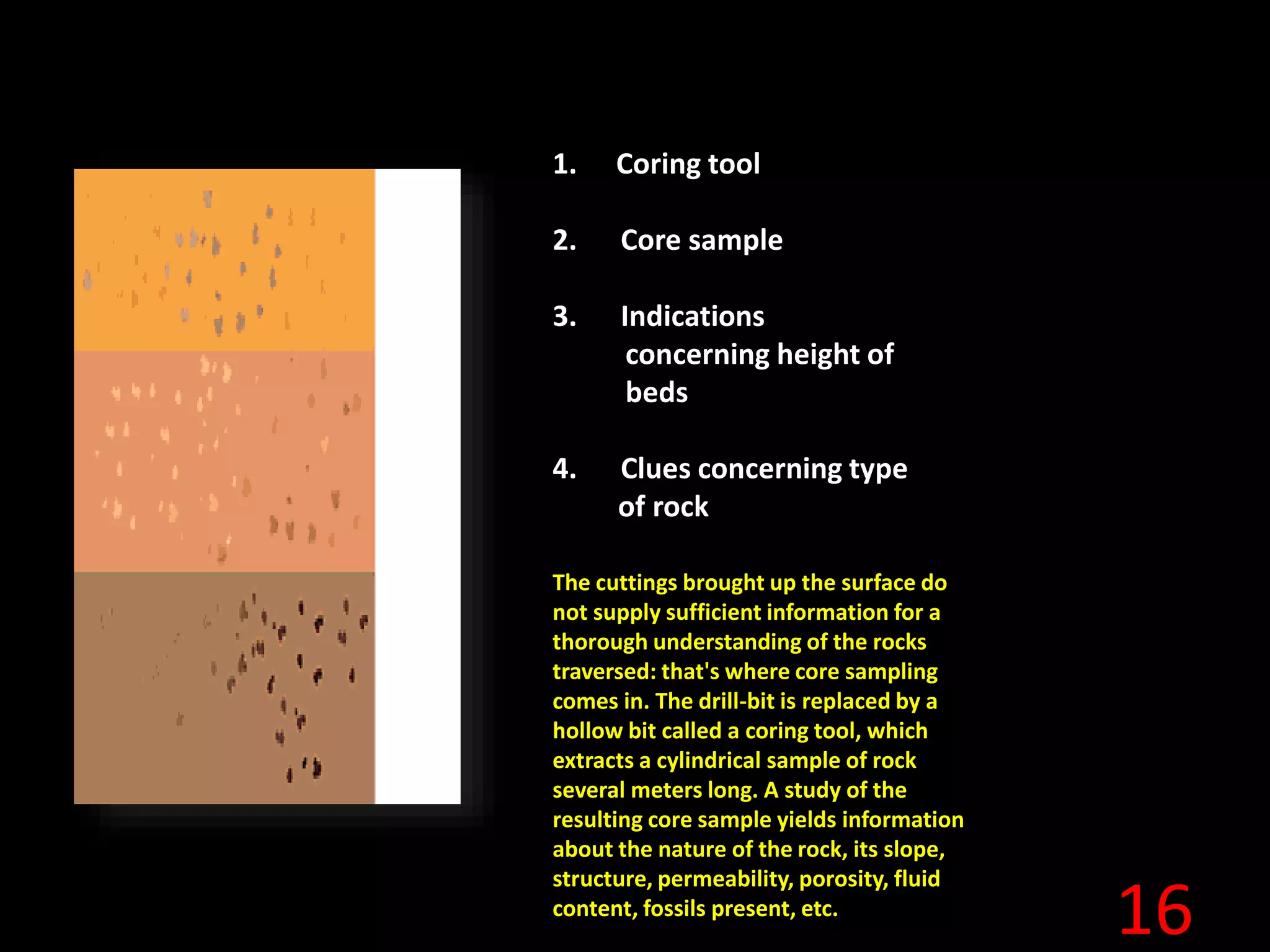

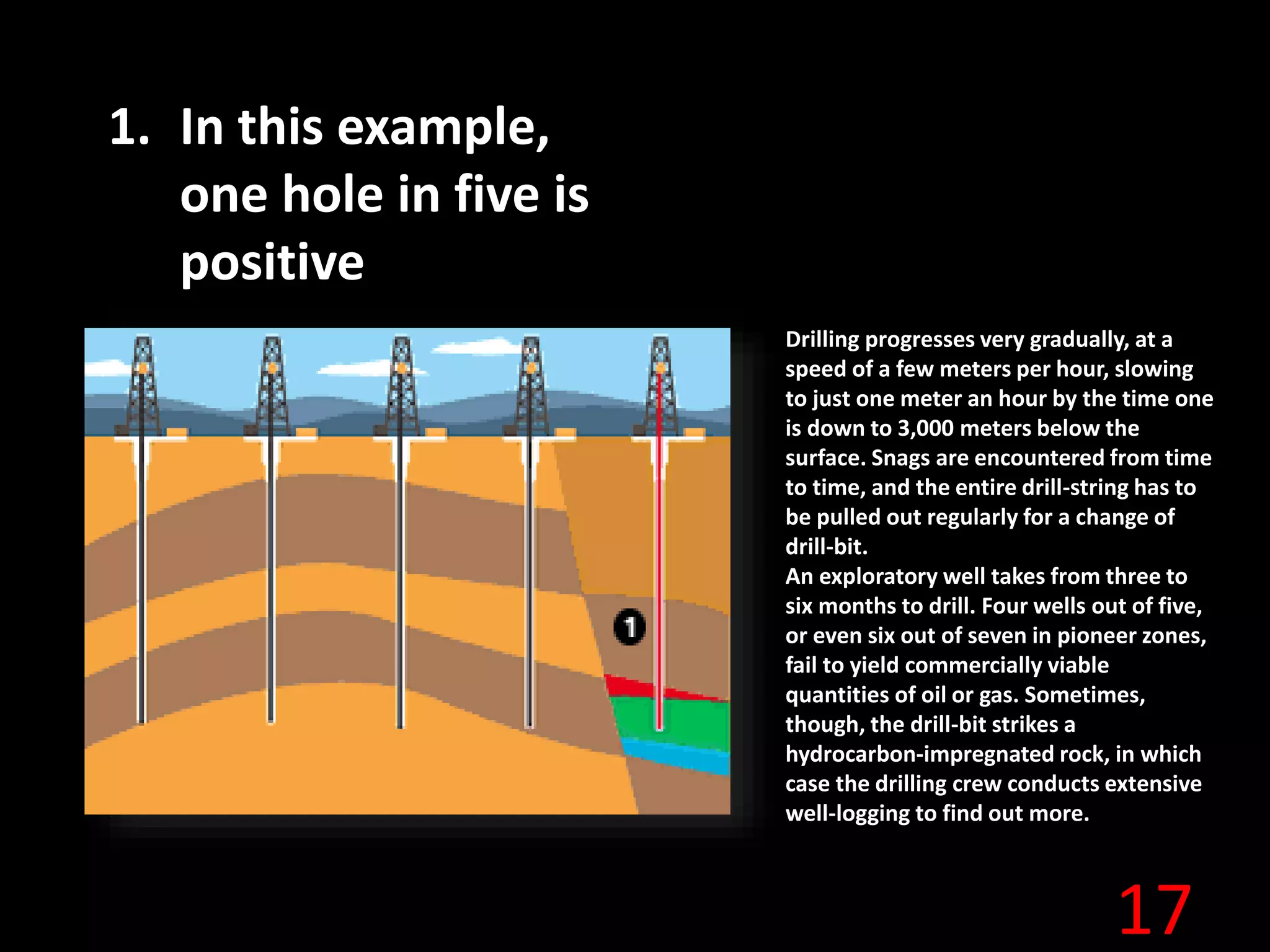

Exploration geophysics uses seismic, gravity, magnetic, electrical, and electromagnetic methods to search for oil, gas, minerals, and water underground. Seismic data is collected using vibrator trucks on land or seismic vessels at sea, and reflected waves are received by geophones or hydrophones. The data is processed to create 2D and 3D images of underground strata. Wells are drilled using a rig and drill string to further explore promising areas identified on seismic maps. If hydrocarbons are found, economic analysis is conducted to determine if developing the reservoir will cover costs and be profitable.