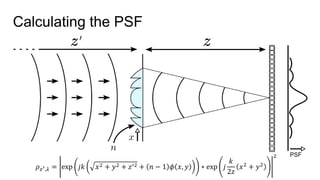

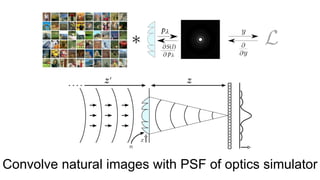

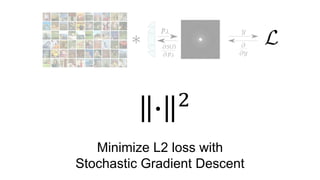

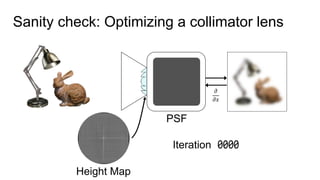

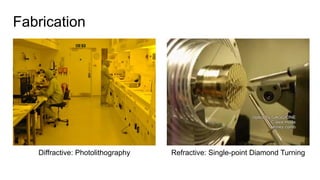

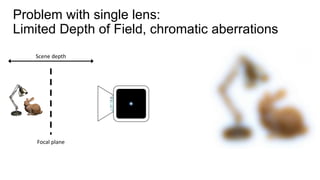

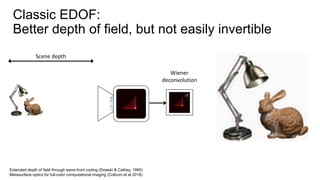

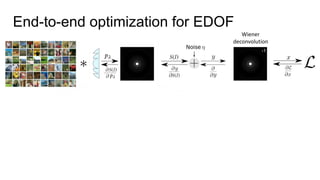

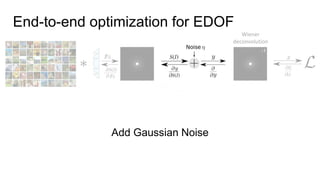

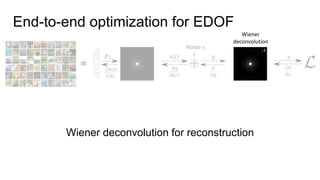

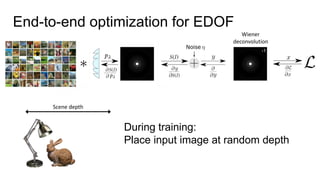

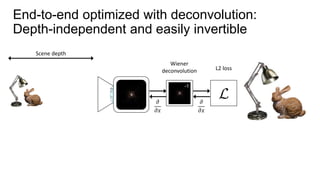

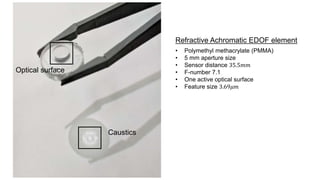

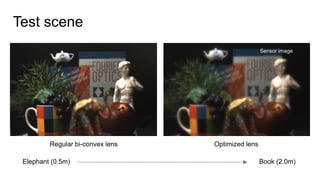

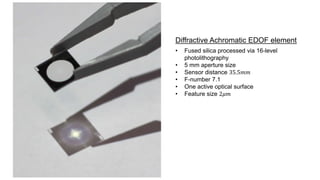

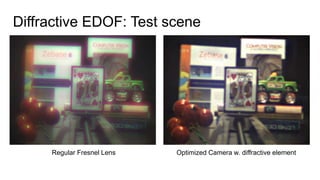

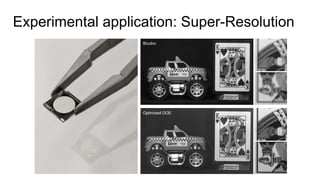

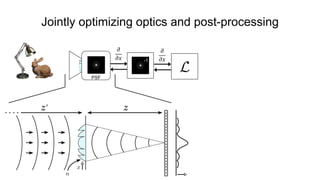

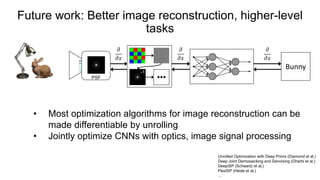

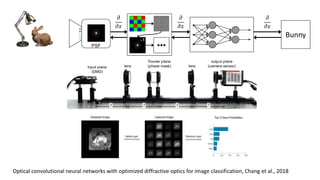

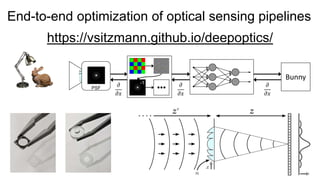

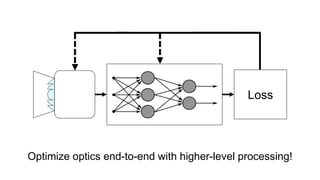

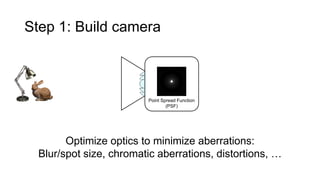

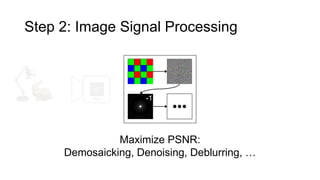

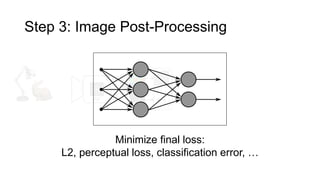

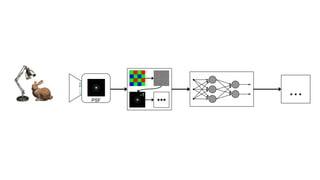

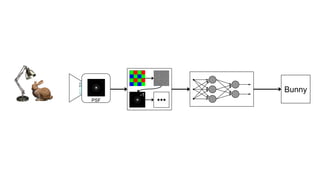

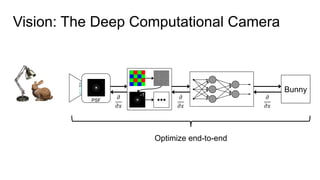

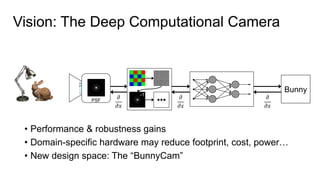

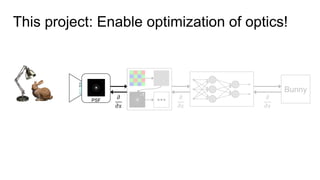

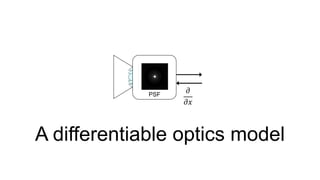

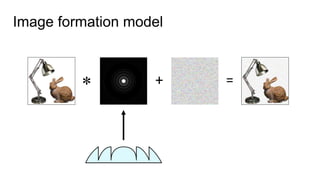

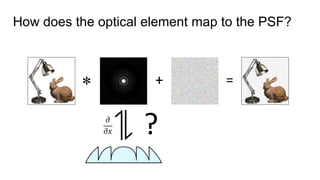

This document discusses the end-to-end optimization of optics and image processing for enhanced imaging techniques, focusing on achieving achromatic extended depth of field (EDOF) and super-resolution. It outlines a pipeline that includes the optimization of optical components to reduce aberrations, followed by image signal processing and final post-processing for improved outcomes. Future work aims to refine image reconstruction methods and integrate optics with image processing frameworks using advanced optimization algorithms.

![Height Map parameterization

(diffractive)

Zernike basis parameterization

(refractive)

Φ 𝑥 = [ 𝑎11, 𝑎12, … , … ] Φ[𝑥] = 𝑍𝑖

𝑗

𝑥 ∙ 𝑎𝑖𝑗](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/learningdomain-specificcameras-180925221706/85/End-to-end-Optimization-of-Cameras-and-Image-Processing-SIGGRAPH-2018-27-320.jpg)