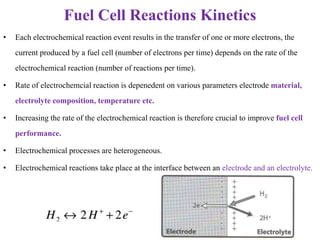

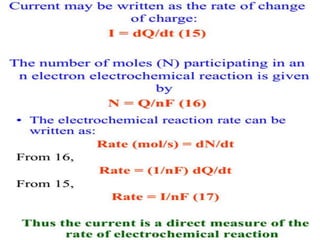

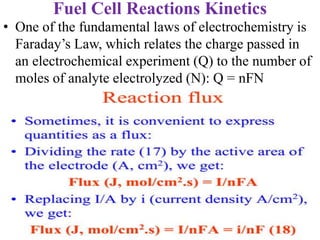

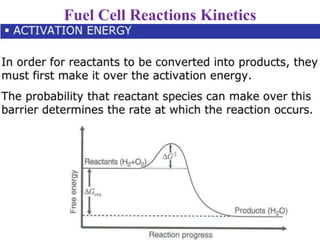

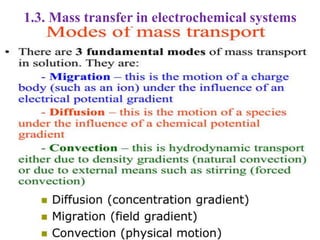

Electrochemistry is the study of chemical reactions caused by the passage of an electric current and the production of electrical energy from chemical reactions. It encompasses phenomena like corrosion and devices like batteries and fuel cells. Electrochemical cells are either electrolytic cells, where an external power source drives non-spontaneous reactions, or galvanic/voltaic cells, where spontaneous reactions produce electricity. The kinetics and rates of electrochemical reactions, as well as mass transfer of reactants, influence current production in fuel cells and other devices.

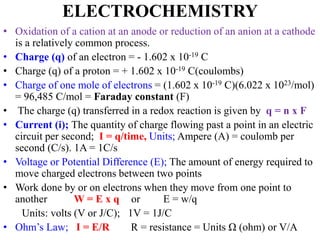

![ELECTROCHEMISTRY

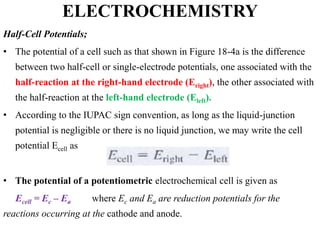

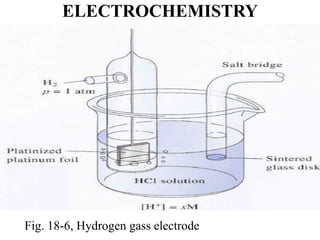

• The half-reaction responsible for the potential that develops at this

electrode is

• The hydrogen electrode shown in Figure 18-6 can be represented

schematically as

Pt, H2(PH2 = 1.00 atm) / ([H+] = x M) //

• Here, the hydrogen is specified as having a partial pressure of one

atmosphere and the concentration of hydrogen ions in the solution is x M.

• The hydrogen electrode is reversible.

• The potential of a hydrogen electrode depends on temperature and the

activities of hydrogen ion and molecular hydrogen in the solution.

• The latter, in turn, is proportional to the pressure of the gas that is used

to keep the solution saturated in hydrogen.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/electrochemistrychapter1-180102043612/85/Electrochemistry-chapter-1-32-320.jpg)