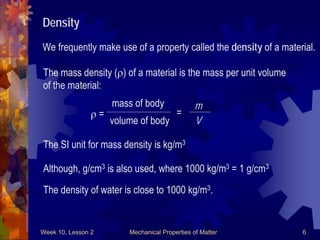

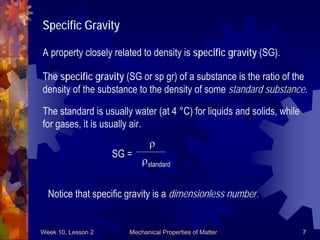

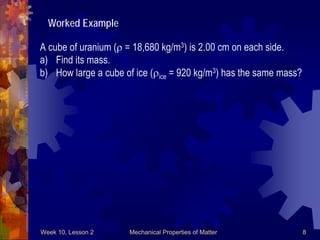

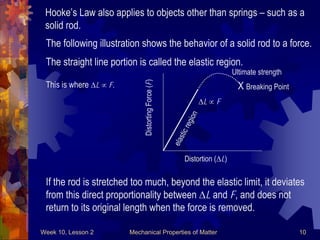

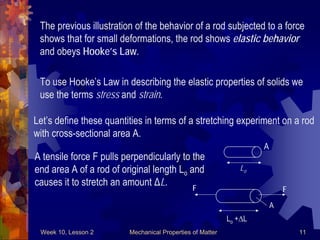

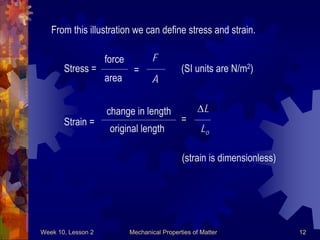

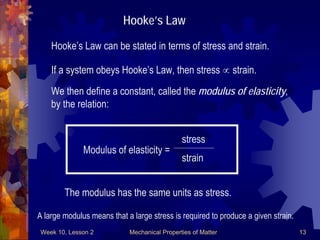

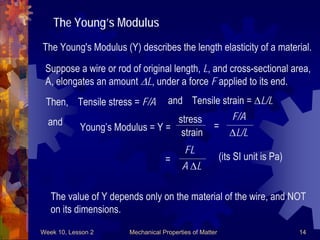

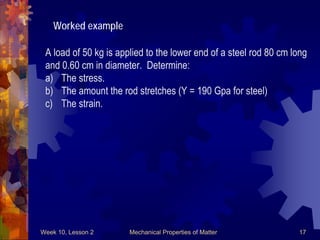

This document discusses mechanical properties of matter such as density, elasticity, and fluid pressure. It defines key terms like density, specific gravity, stress, strain, and Hooke's law. Hooke's law states that the deformation of a material is proportional to the force applied. Young's modulus is introduced as a measure of a material's elasticity, relating stress to strain. Examples are worked through to demonstrate calculating density, specific gravity, stress, strain, and deformation based on given values and materials.