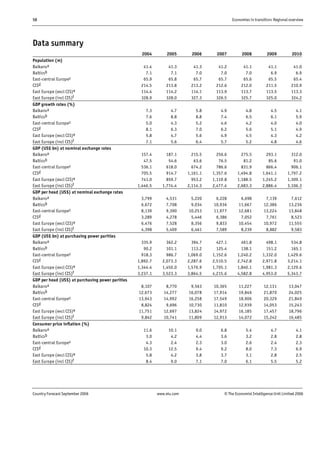

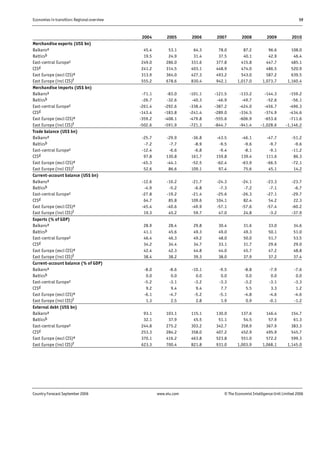

The document provides a regional overview of economies in transition in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, highlighting the contributions of financial sector development to economic growth. Despite political uncertainties, the economic outlook is favorable, with projected growth rates above 5% for the period of 2006-2010. It notes that foreign direct investment inflows and improvements in business environments are expected, although risks remain related to slow reforms and financial stability.