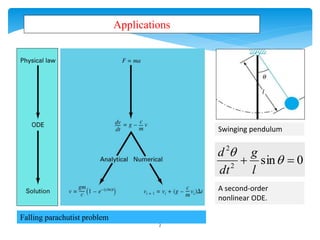

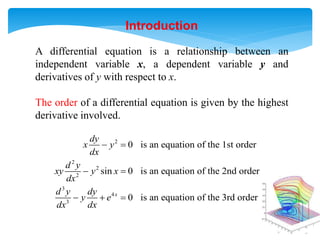

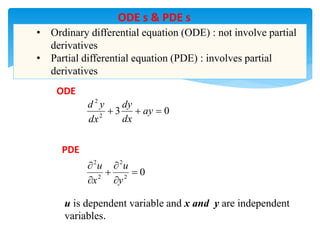

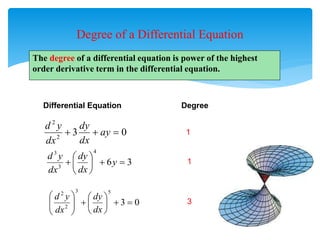

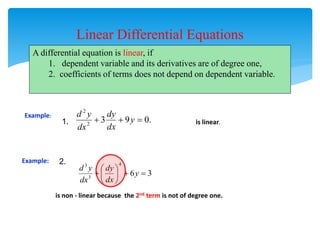

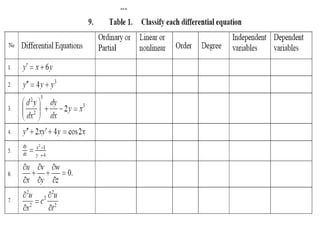

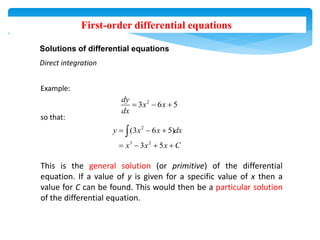

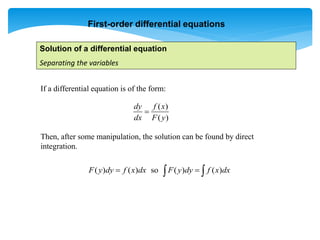

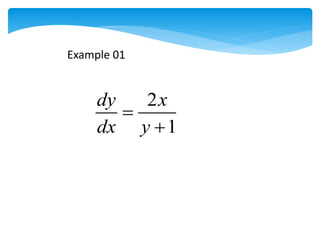

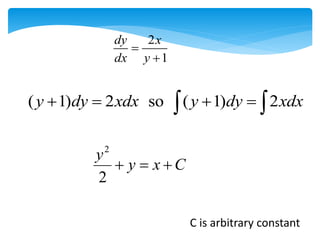

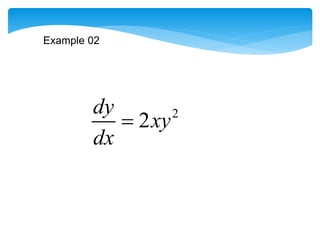

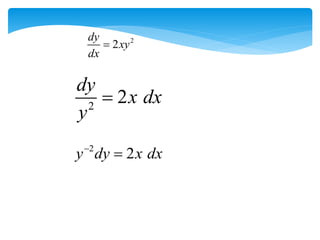

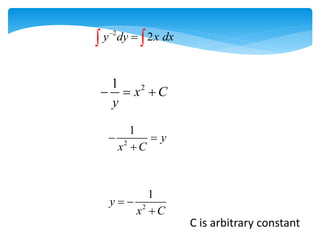

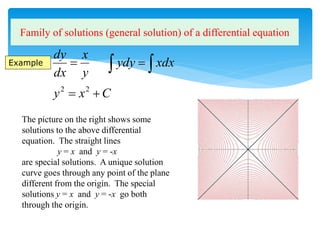

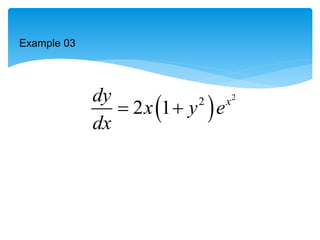

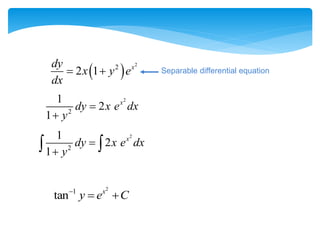

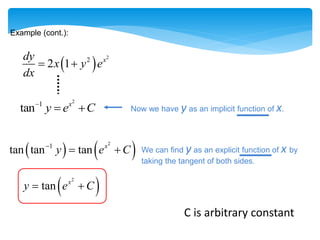

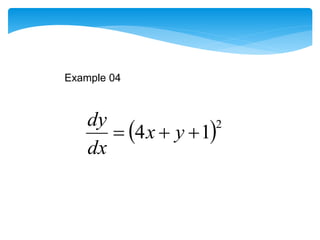

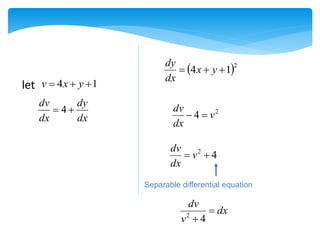

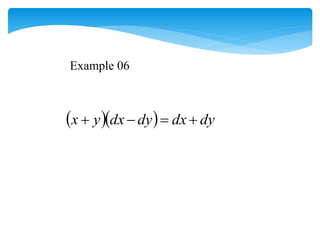

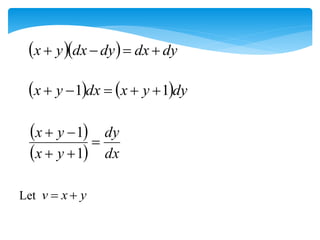

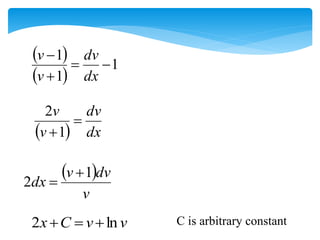

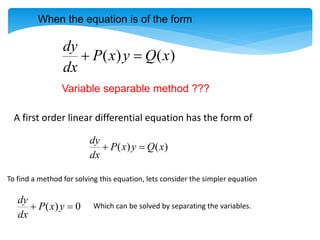

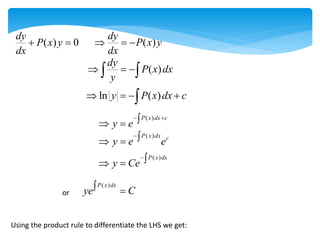

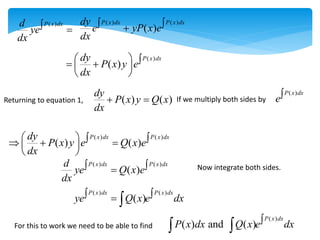

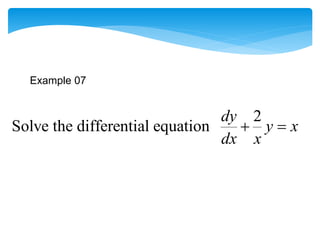

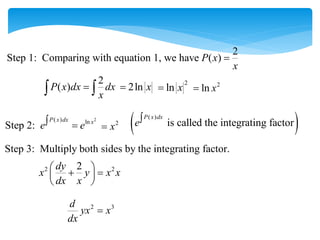

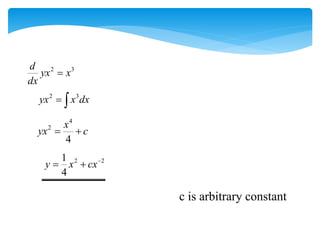

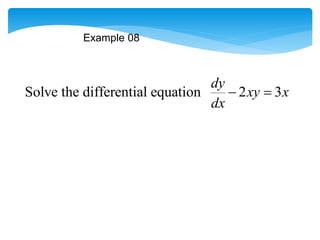

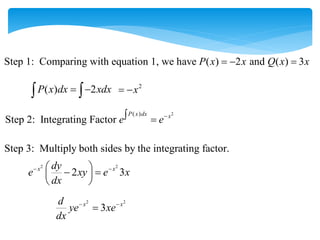

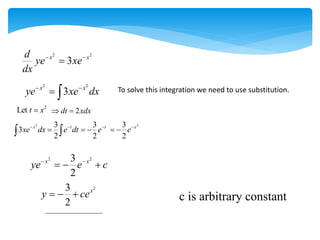

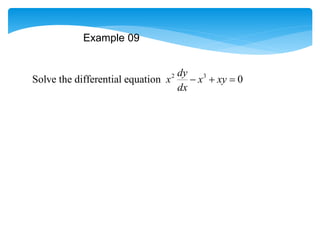

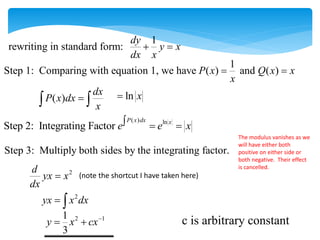

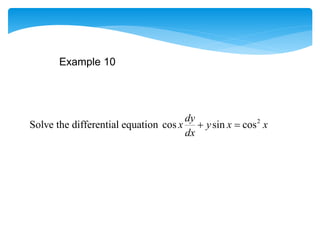

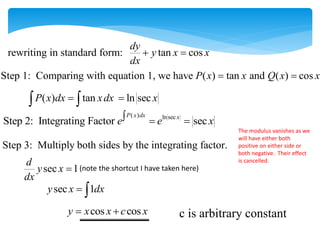

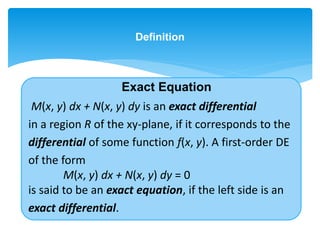

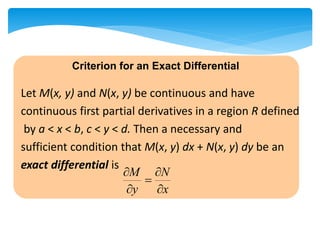

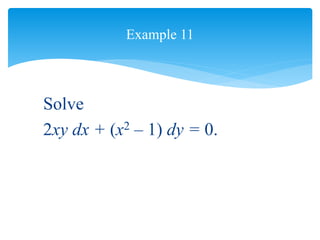

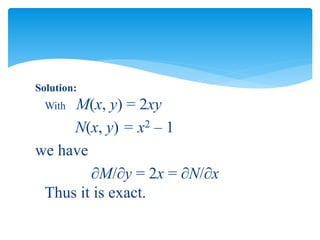

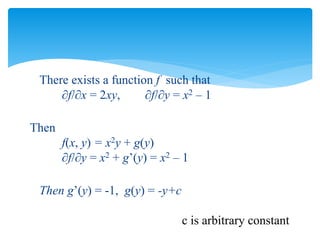

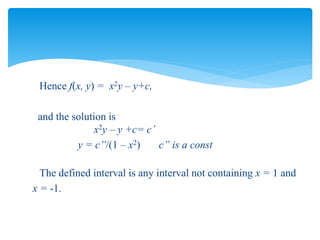

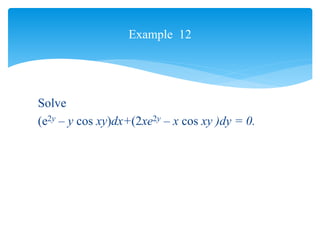

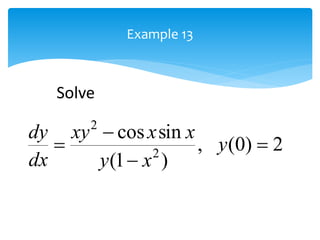

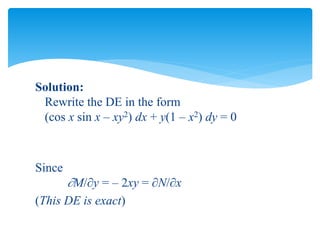

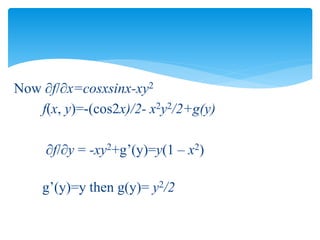

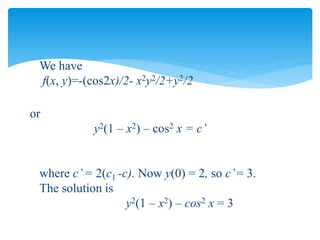

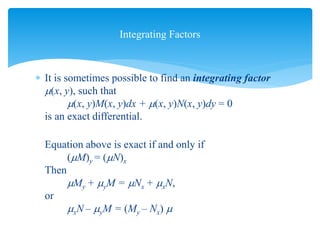

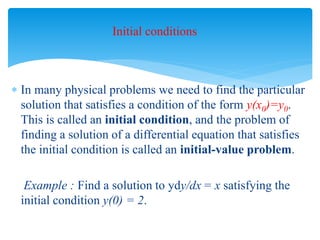

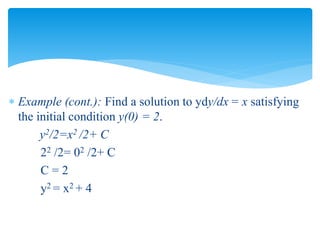

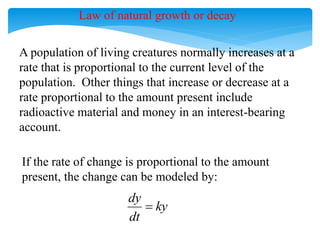

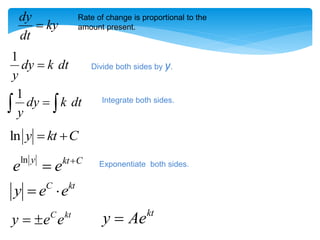

This document discusses differential equations. It defines differential equations and explains that the order refers to the highest derivative. It distinguishes between ordinary and partial differential equations. It also covers topics like the degree of a differential equation, linear vs nonlinear, and methods for solving first-order differential equations like separation of variables and integrating factors. Examples are provided to illustrate various types of first-order differential equations and solution methods.