This document provides an introduction to usability, including:

- Defining usability as the ease of use and quality of user experience when interacting with something.

- Explaining the history of usability originated from human factors research during WWII to ensure users could operate weapons and technology.

- Detailing common definitions of usability focus on effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction of users achieving goals in a particular environment.

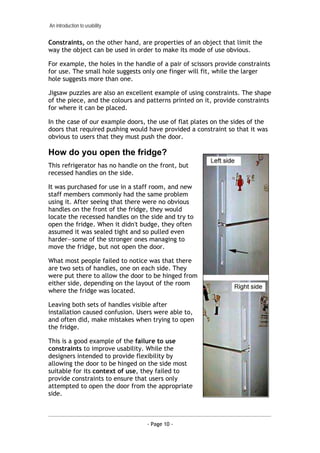

- Outlining key aspects of usability like being effective, efficient, engaging, error tolerant and easy to learn.