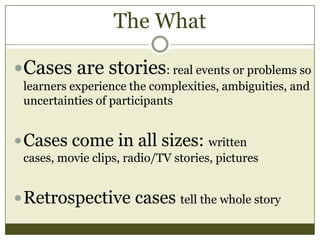

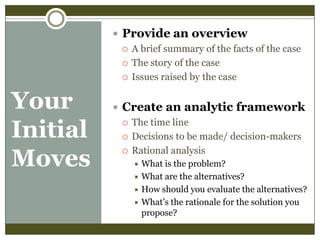

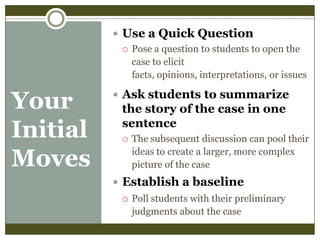

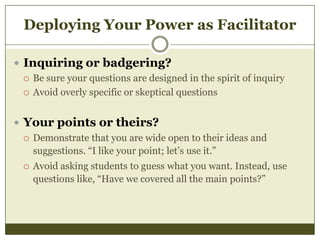

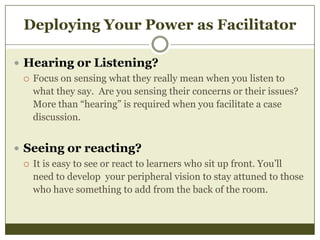

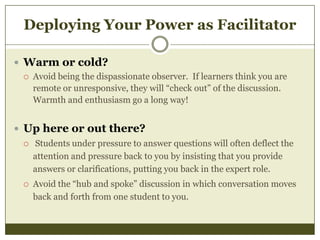

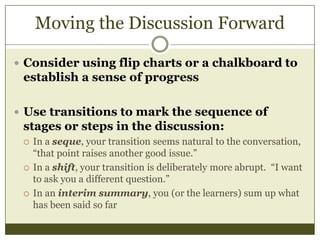

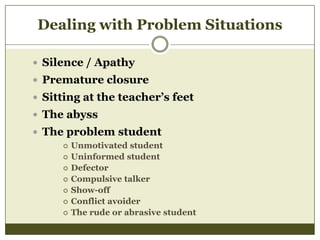

This document provides guidance on developing effective case studies for teaching in medical education. It discusses what makes a good case, such as using real-life stories and problems to illustrate complexities. It also offers tips for facilitating case study discussions, such as providing an overview of the case, creating an analytic framework, and using questions to engage students. The document emphasizes allowing students to guide the discussion and provides strategies for managing challenges that may arise.