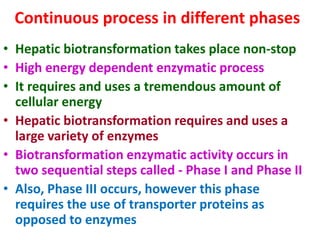

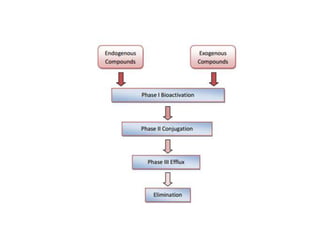

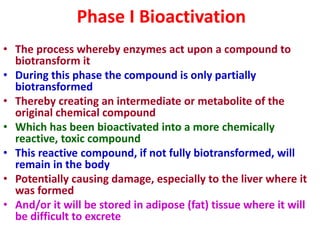

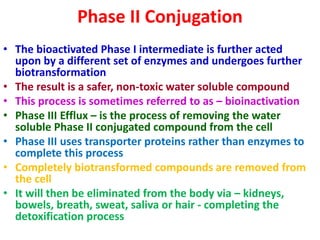

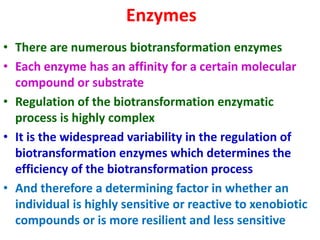

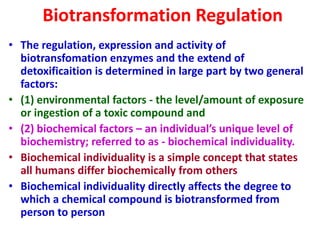

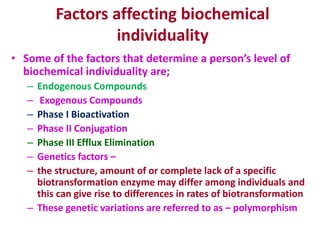

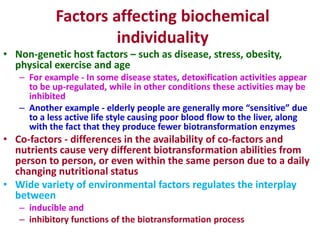

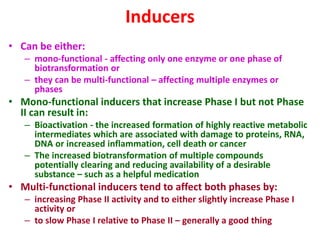

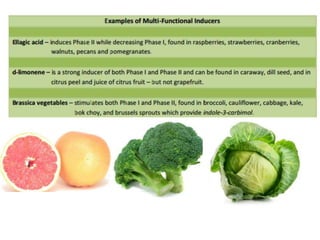

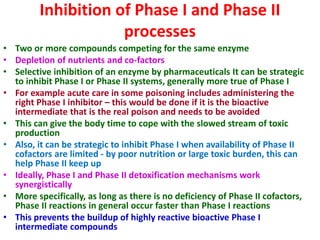

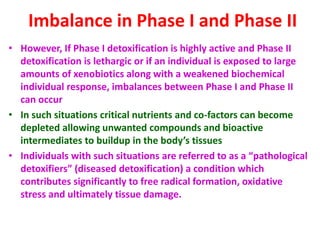

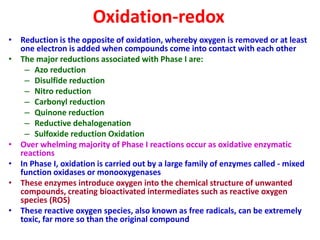

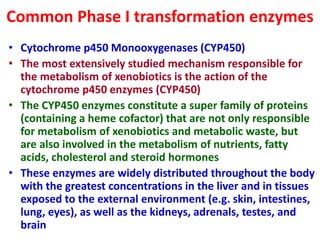

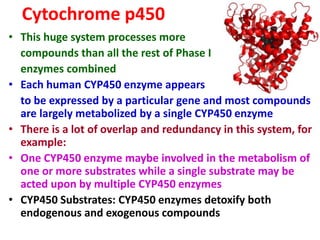

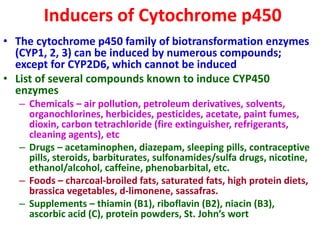

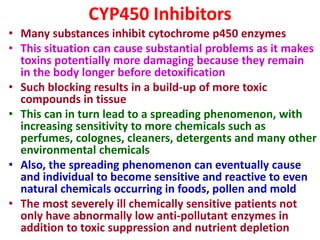

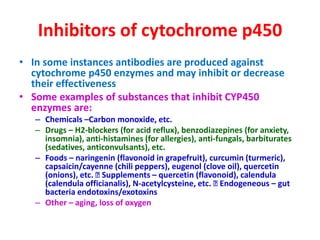

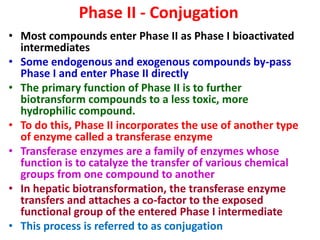

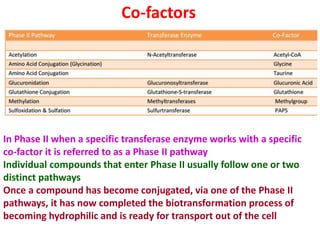

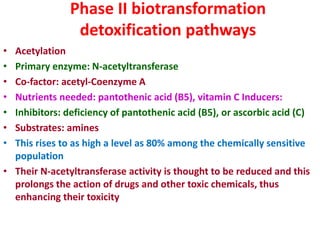

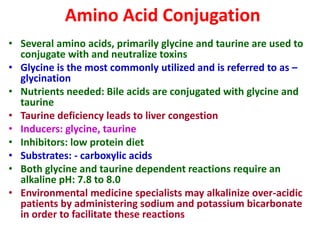

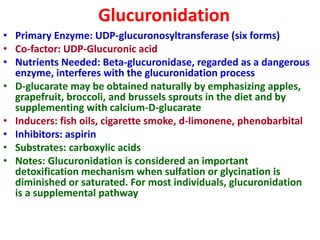

The document summarizes the two-phase process of detoxification in the liver. Phase I involves enzymatic reactions like oxidation and reduction that activate toxins. This can create reactive intermediates. Phase II then conjugates these intermediates to make them more water-soluble and able to be excreted. Many factors influence individual detoxification capacity, like genetic variations in enzyme expression as well as environmental exposures and nutrient status. Imbalances between phases can allow toxins to accumulate.