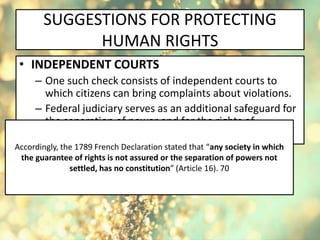

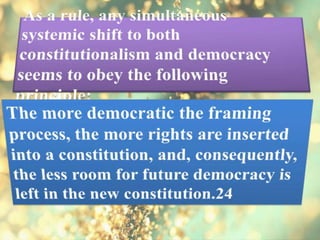

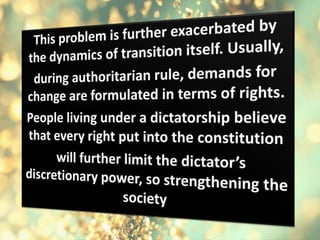

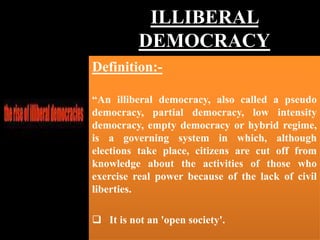

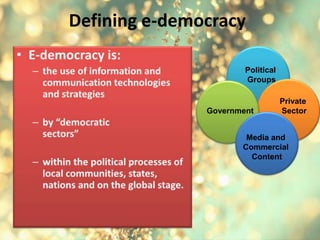

Democracy and human rights are interdependent. True democracy requires the protection of individual dignity through human rights. Constitutional democracies protect both democratic principles and individual rights through separation of powers, an independent judiciary, and the protection of civil liberties and minority rights in the constitution. However, an excess of constitutional rights can weaken democracy by limiting the room for public debate and policymaking. Illiberal and populist democracies undermine separation of powers and civil liberties in the name of majority rule. E-democracy uses digital technologies to enhance citizen participation in political processes at various levels of government.