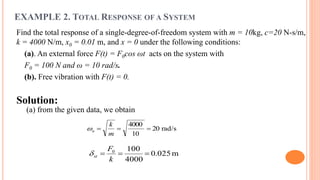

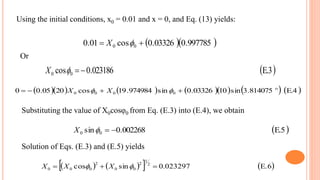

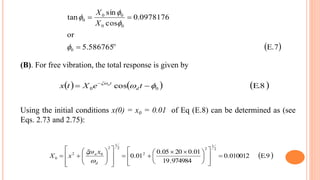

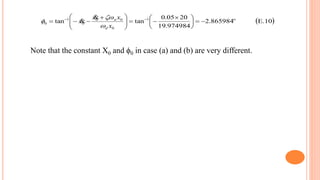

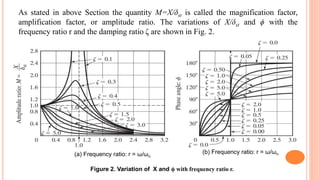

This document provides information about the dynamics of machinery course for several mechanical engineering students. It includes the learning objectives, symbols and definitions, response of a damped system under harmonic motion, an example problem, and key concepts about magnification factor, phase angle, and total response of a system. The example calculates the total response of a single-degree-of-freedom system subjected to an external harmonic force and free vibration.

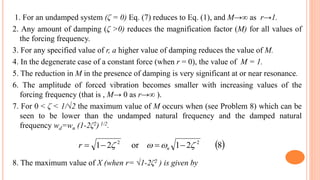

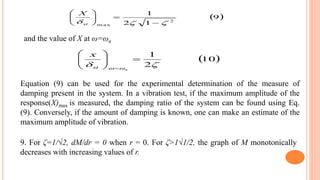

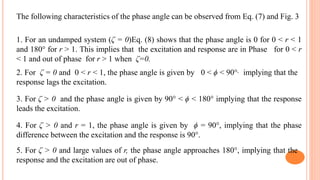

![X and ϕ are given by Eqs. (7) and (8), respectively, X0 and ϕ0 [different from those of

Eq. (2)] can be determined from the initial conditions. For the initial conditions

x(t=0)= x0, and x(t=0)=x0 Eq. (11) yields

nd 2

1

12sinsincos

coscos

00000

000

XXXx

XXx

dn

11coscos 00

tXteXtx d

tn

The solution of Eq. (12) gives X0and ϕ0 as

13

cos

sincos

tan

sincos

1

cos

0

0

0

2

1

2

002

2

00

Xx

XXxx

XXxxXxX

d

nn

nn

d

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/mech6051-55-180529050731/85/Damped-system-under-Harmonic-motion-15-320.jpg)