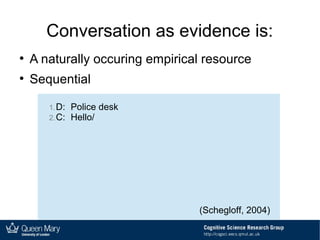

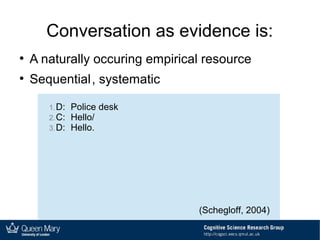

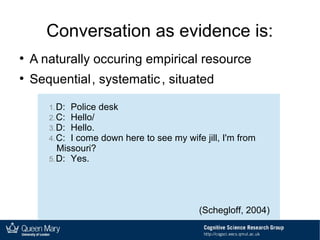

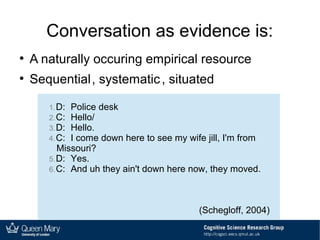

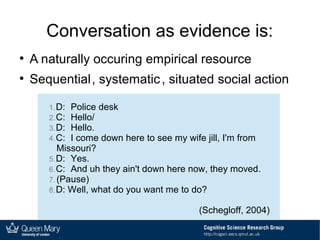

The document discusses conversation analysis (CA) as a systematic method for understanding human interactions and practical reasoning. It emphasizes the importance of everyday chat as a unique empirical resource and outlines how this analysis can help reveal participants' reasoning methods through sequential social actions. The text also highlights the significance of CA for those in technical fields, suggesting that it treats conversation as a practical technology.

![Talk-in-interaction's proof practices:

●

Enlist participants' own methods of reasoning

●

In revealing and resolving problems in talk

1. Fda: =This is nice did you make this?

2. Kat: No Samu made that

3. Fda: Who?

4. Kat: Samu

5. (0.1)

6. Kat: (Sh) You remember my [aunt? ]

7. Dav: [Aunt S ]amu

8. Kat: [From Czechoslovakia?

9. Fda: [Yyeeah

10.Fda: Oh she’s really something

11.Kat: Yeah

(Schegloff & Lerner, 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/conversationanalysisforgeeks-2013-separate-130703014457-phpapp02/85/Conversation-analysis-for-geeks-18-320.jpg)

![Talk-in-interaction's proof practices:

●

Enlist participants' own methods of reasoning

●

In revealing and resolving problems in talk

1. Fda: =This is nice did you make this?

2. Kat: No Samu made that

3. Fda: Who?

4. Kat: Samu

5. (0.1)

6. Kat: (Sh) You remember my [aunt? ]

7. Dav: [Aunt S ]amu

8. Kat: [From Czechoslovakia?

9. Fda: [Yyeeah

10.Fda: Oh she’s really something

11.Kat: Yeah

(Schegloff & Lerner, 2009)

1. Fda: =This is nice did you make this?

2. Kat: No Samu made that

3. Fda: Who?

4. Kat: Samu

5. (0.1)

6. Kat: (Sh) You remember my [aunt? ]

7. Dav: [Aunt S ]amu

8. Kat: [From Czechoslovakia?

9. Fda: [Yyeeah

10.Fda: Oh she’s really something

11.Kat: Yeah

(Schegloff & Lerner, 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/conversationanalysisforgeeks-2013-separate-130703014457-phpapp02/85/Conversation-analysis-for-geeks-19-320.jpg)

![Talk-in-interaction's proof practices:

●

Enlist participants' own methods of reasoning

●

In revealing and resolving problems in talk

1. Fda: =This is nice did you make this?

2. Kat: No Samu made that

3. Fda: Who?

4. Kat: Samu

5. (0.1)

6. Kat: (Sh) You remember my [aunt? ]

7. Dav: [Aunt S ]amu

8. Kat: [From Czechoslovakia?

9. Fda: [Yyeeah

10.Fda: Oh she’s really something

11.Kat: Yeah

(Schegloff & Lerner, 2009)

1. Fda: =This is nice did you make this?

2. Kat: No Samu made that

3. Fda: Who?

4. Kat: Samu

5. (0.1)

6. Kat: (Sh) You remember my [aunt? ]

7. Dav: [Aunt S ]amu

8. Kat: [From Czechoslovakia?

9. Fda: [Yyeeah

10.Fda: Oh she’s really something

11.Kat: Yeah

(Schegloff & Lerner, 2009)

1. Fda: =This is nice did you make this?

2. Kat: No Samu made that

3. Fda: Who?

4. Kat: Samu

5. (0.1)

6. Kat: (Sh) You remember my [aunt? ]

7. Dav: [Aunt S ]amu

8. Kat: [From Czechoslovakia?

9. Fda: [Yyeeah

10.Fda: Oh she’s really something

11.Kat: Yeah

(Schegloff & Lerner, 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/conversationanalysisforgeeks-2013-separate-130703014457-phpapp02/85/Conversation-analysis-for-geeks-20-320.jpg)

![Talk-in-interaction's proof practices:

●

Enlist participants' own methods of reasoning

●

In revealing and resolving problems in talk

1. Fda: =This is nice did you make this?

2. Kat: No Samu made that

3. Fda: Who?

4. Kat: Samu

5. (0.1)

6. Kat: (Sh) You remember my [aunt? ]

7. Dav: [Aunt S ]amu

8. Kat: [From Czechoslovakia?

9. Fda: [Yyeeah

10.Fda: Oh she’s really something

11.Kat: Yeah

(Schegloff & Lerner, 2009)

1. Fda: =This is nice did you make this?

2. Kat: No Samu made that

3. Fda: Who?

4. Kat: Samu

5. (0.1)

6. Kat: (Sh) You remember my [aunt? ]

7. Dav: [Aunt S ]amu

8. Kat: [From Czechoslovakia?

9. Fda: [Yyeeah

10.Fda: Oh she’s really something

11.Kat: Yeah

(Schegloff & Lerner, 2009)

1. Fda: =This is nice did you make this?

2. Kat: No Samu made that

3. Fda: Who?

4. Kat: Samu

5. (0.1)

6. Kat: (Sh) You remember my [aunt? ]

7. Dav: [Aunt S ]amu

8. Kat: [From Czechoslovakia?

9. Fda: [Yyeeah

10.Fda: Oh she’s really something

11.Kat: Yeah

(Schegloff & Lerner, 2009)

1. Fda: =This is nice did you make this?

2. Kat: No Samu made that

3. Fda: Who?

4. Kat: Samu

5. (0.1)

6. Kat: (Sh) You remember my [aunt? ]

7. Dav: [Aunt S ]amu

8. Kat: [From Czechoslovakia?

9. Fda: [Yyeeah

10.Fda: Oh she’s really something

11.Kat: Yeah

(Schegloff & Lerner, 2009)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/conversationanalysisforgeeks-2013-separate-130703014457-phpapp02/85/Conversation-analysis-for-geeks-21-320.jpg)