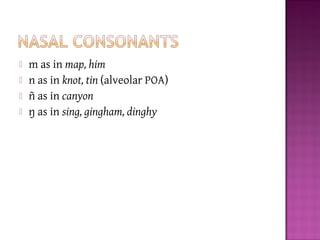

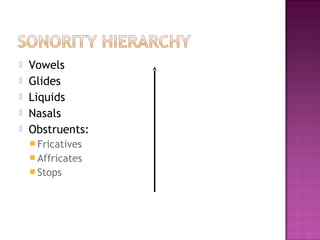

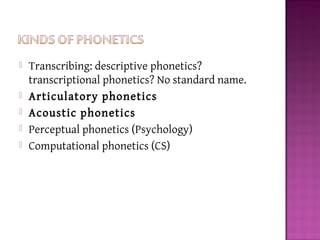

This document provides an overview of phonetic transcription and the analysis of sounds in language. It discusses the major categories of sounds in English including consonants and vowels. For consonants, it lists the place and manner of articulation for common consonant sounds. It notes there are 6 stop consonants, 9 fricatives, 2 affricates, 4 nasals, and 2 other sonorants. For vowels, it indicates they are harder to characterize articulatorily but notes some of the vowel symbols used in the International Phonetic Alphabet and Americanist phonetic notation. The document emphasizes phonetic transcription aims to characterize the inventory of sounds in a language through symbols while accounting for cross-speaker and contextual sound variations.

![Consonants: first, the stops:

b as in bat, sob, cubby

d as in date, hid, ado

g as in gas, lag, ragged

p as in pet, tap, repeat

t as in tap, pet, attack

k as in king, pick, picking

When we need to emphasize

that we are using a phonetic

transcription, we put square

brackets [b] around the symbols.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/consonantsandvowels-151006143326-lva1-app6892/85/Consonants-and-vowels-6-320.jpg)