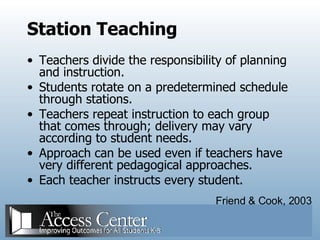

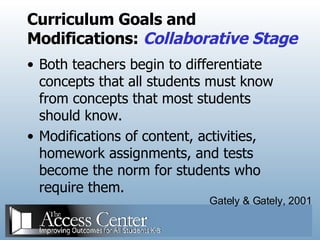

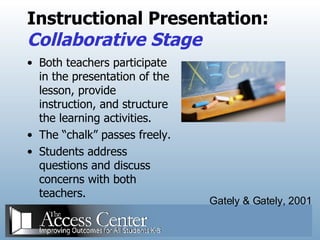

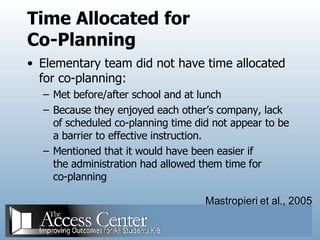

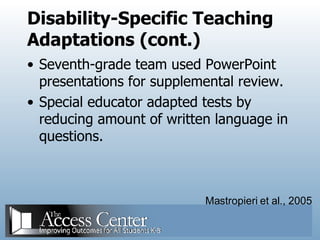

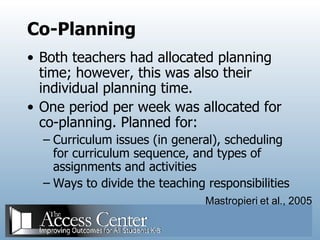

This document provides an overview of collaborative teaching and co-teaching strategies to improve access to the general curriculum for students with disabilities. It discusses the benefits of co-teaching, examples of co-teaching approaches like one teach one assist and parallel teaching. It emphasizes the importance of co-planning and getting to know your co-teaching partner. Administrators are encouraged to support co-teaching by providing co-planning time and a gradual implementation process.