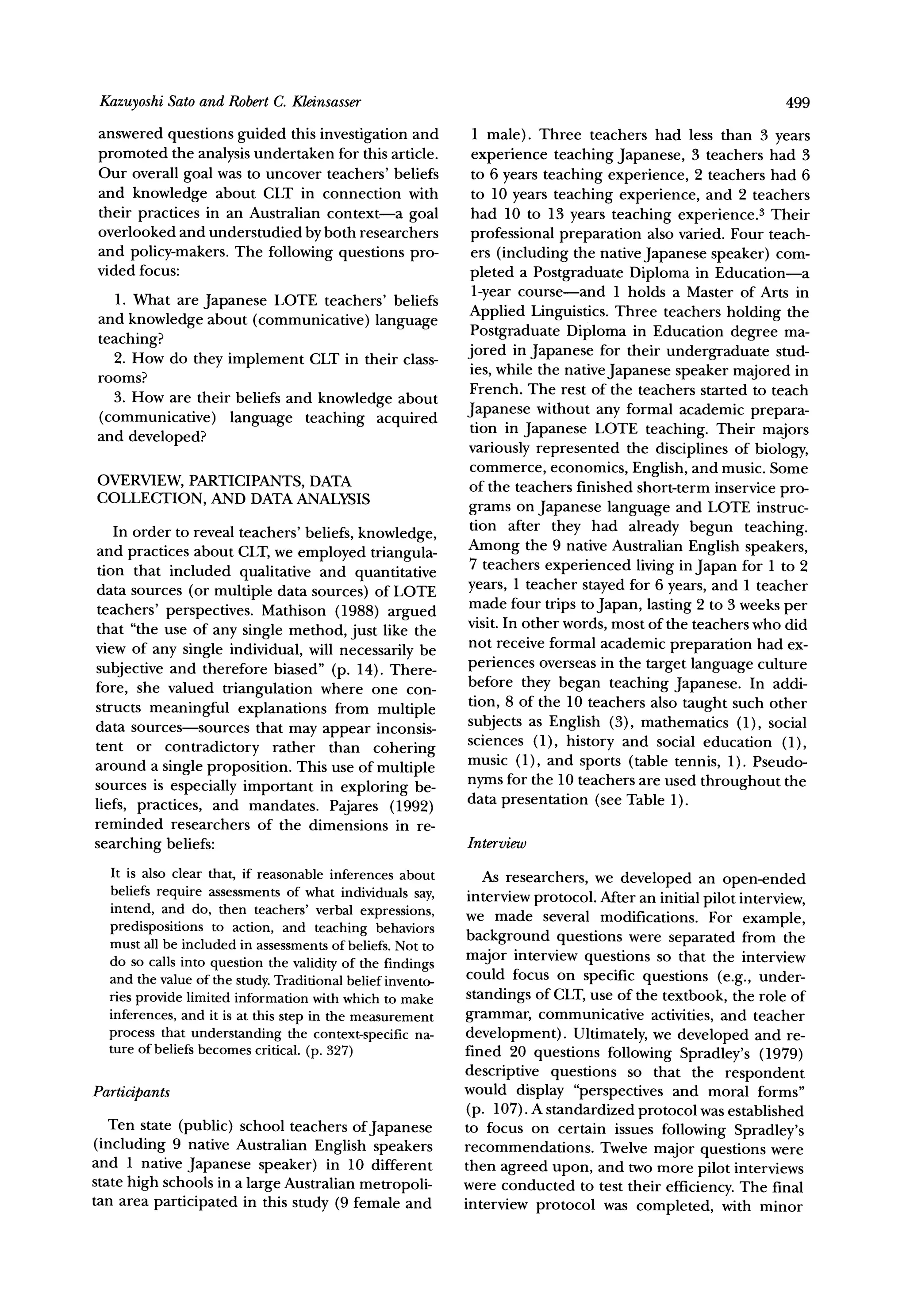

This document summarizes a research study that investigated Japanese second language teachers' understanding and implementation of communicative language teaching (CLT). The study used interviews, classroom observations, and surveys to understand how teachers defined CLT and applied it in their classrooms. The study found that teachers' views and practices of CLT were influenced more by their own experiences than by academic literature on CLT or their teacher training. Teachers developed their own conceptions of how to teach foreign languages based on personal ideas and experiences over time.

![Sato and RobertC. Kleinsasser

Kazuyoshi 497

slightly with the view that teachers' decision-mak- classrooms, they offered students few opportuni-

ing is based upon knowledge and skills [e.g., ties for genuine communicative language use in

Shulman, 1986, 1987]). the class sessions that he recorded. Although the

Regardless of theoretical stance, empirical lesson plans of these teachers might have con-

studies consistently reveal the difficulties of pro- formed to the sorts of communicative principles

moting knowledge and skills that challenge or advocated in the CLT literature, the actual pat-

contradict currently held beliefs and practices terns of classroom interaction resembled tradi-

(see, e.g., the reviews by Richardson, 1996, and tional patterns rather than what he identified as

Wideen, Mayer-Smith, & Moon, 1998). In L2 genuine interaction. Karavas-Doukas (1996) re-

teacher studies in general, there is definitely a ported similar findings in the responses of 14

tendency for those studied to rely on their pre- Greek teachers of English to an attitude survey

conceived beliefs, and there appears to be little and in the observations she made of their class-

alteration in traditionally (form focus, teacher- rooms. She found that the survey results leaned

led) held images of L2 teaching (see, e.g, toward agreement with CLT principles, but when

Johnson, 1994; Lamb, 1995; Neustupny, 1981). she observed the classroom teaching environ-

Nonetheless, studies that specifically single out ments, "classroom practices (with very few excep-

typical CLT also reveal glimpses of links among tions) deviated considerably from the principles

beliefs, knowledge, and practices. On the one of the communicative approach" (p. 193). Al-

hand, a few studies show little change in teacher though she acknowledged that there were

beliefs, knowledge, or practice, whereas, on the glimpses of communicative approaches, the

other hand, a few studies reveal the possibility for teachers in her sample favored traditional ones.

change in teacher beliefs, knowledge, or practice. In this case, traditional meant, "Mostlessons were

Thus, these studies provide evidence that the teacher-fronted and exhibited an explicit focus

challenges found in L2 teaching literature are on form" (p. 193).

little different from the controversy in the wider As indicated earlier, not all of the news is bleak.

teaching literature. The extent to which teachers Okazaki (1996) completed a longitudinal study

can or will actually change is an issue within using surveys to find out whether preservice

teacher education, regardless of discipline. teachers changed their beliefs concerning CLT

For example, Thompson (1996) discovered after a 1-year methodology course. She con-

four misconceptions that were common among cluded that although beliefs of preservice teach-

his colleagues concerning the meaning of CLT: ers were not easily swayed, some of them were

(a) not teaching grammar, (b) teaching only influenced in the desired direction by what Wen-

speaking, (c) completing pair work (i.e., role den (1991) called persuasive communication,

play), and (d) expecting too much from teachers. which aims at changing participants' beliefs by

Thompson mentioned that a surprisingly large reflective teaching. For example, she reported

number of teachers invoke erroneous reasoning that the teachers' emphasis increased on such

for criticizing or rejecting CLT. He concluded items as the learner's role and decreased on such

that the future development of CLT depended items as pronunciation and error corrections. Ku-

upon correcting these misconceptions. Fox maravadivelu (1993) studied two teachers whom

(1993) surveyed first-yearFrench graduate teach- he identified as "'believers' in the CLT move-

ing assistants at 20 universities in the U.S. and ment" (p. 14), and who both had masters degrees

analyzed their responses according to the defini- in ESL. With one teacher he promoted the effec-

tions of communicative competence (CC) set tiveness of five macrostrategies for successful CLT

forth by Canale and Swain (1980). She reported (see also Kumaravadivelu, 1992). He then tran-

that teaching assistants did not conceptualize lan- scribed the two teachers' classes and concluded

guage according to this particular model of CC. that the episodes showed "different kinds of class-

Instead, the participants relied on grammar at room input and interaction" (p. 18). One group

the expense of communicative activities. She con- was motivated, enthusiastic, and active. The same

cluded that their beliefs about language teaching group in the second session was less motivated,

and learning should be exposed so that they less enthusiastic, and much less active. Although

could develop their beliefs and knowledge about he identified session one as a speaking class, and

CLT. session two as a grammar class, he believed that

Even teachers committed to CLT often seem to the use of the macrostrategies given to the

show a very superficial adherence to CLT princi- teacher in session one "contributed to this re-

ples. As Nunan (1987) discovered, although the markable variation in the communicative nature

teachers in his study had goals for communicative of the two episodes" (p. 18). Regardless of the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cltinpractice-130226135546-phpapp01/75/Clt-in-practice-5-2048.jpg)

![Sato and RobertC. Kleinsasser

Kazuyoshi 501

of 3.6 or higher were those with which teachers veys, while also offering a glimpse of what actually

agreed (the closer to 5, the more strongly teach- happened in Japanese language teachers' class-

ers agreed with it). Those items receiving a mean rooms. Their conceptions of CLT serve as a cata-

of 2.4 or lower were those with which teachers lyst to promote their understandings. We hope to

disagreed. Items falling between 2.4 and 3.6 were show that the challenges they face help clarify, in

those with which teachers neither agreed nor dis- part, why they understand CLT the way they do.

agreed, perhaps giving evidence of some uncer- In the second part, we uncover where these teach-

tainty among the participants as a group. ers think they learned about CLT. We acknowl-

edge how teachers situate their own under-

Analysis standings about CLT (and L2 teaching, in

general). The three data sources help articulate

In the main, qualitative inductive approaches how these LOTE teachers view (communicative)

were used to analyze the data for this article (for language teaching as an evolving enterprise, a

complete introductory discussion see Glesne & phenomenon that continually challenges them in

Peshkin, 1992). In this instance, data were pe- their hourly, daily, monthly, and yearly L2 teach-

rused and trends, categories, and classifications ing and learning experiences.

were developed using the constant comparative

method, suggested by Glaser and Strauss (1967), Towarda Definition of (Practical)CLT

and other similar procedure descriptions or

analysis suggestions from more recent publica- The teachers gave few complete descriptions

tions (e.g., Foss & Kleinsasser, 1996; Kleinsasser, about what CLT was and held varying, even frag-

1993). Themes that emerged from the various mented, views. Yet, these fragmented views can be

data sources were identified, compared, and de- explained by the challenges these teachers faced.

veloped into the analysis presented below for the The 10 participants revealed their beliefs about

L2 profession. In addition, the act of writing itself CLT in broad terms and many concurred that

was also part of the analysis. As Krathwohl (1993) CLT was neither fully articulated nor necessarily

suggested, an integral part of their instructional repertoires.

Writingenforces a discipline that helps articulate

half-formed ideas. Somethinghappens between the Language Teachers

WhatJapanese Said, Responded,

formationof an idea and its appearance paper,a

on and Did

latencythat somehowresultsin the clarificationand

untanglingof our thinking.Writinghelps bring un- One teacher eloquently overviewed the notion

conscious processingto light as articulatedsynthe- that CLT was not yet established, giving valuable

sizedstatements.(p. 81)

insight into many of the teachers' feelings. A sen-

Glesne and Peshkin (1992) reminded that: "The timent that CLT was a "work in progress" fore-

act of writing also stimulates new thoughts, new shadowed evolving understandings of CLT by the

connections. Writing is rewarding in that it cre- participants in this study. When asked, "How do

ates the product, the housing for the meaning you define CLT?"she replied:

that you and others have made of your research

It'sa difficultquestion.Well,I supposethe definition

adventure. Writing is about constructing a text" of [a] CLT method has not been establishedyet.

(p. 151). Moreover, the researchers sought to de- There are some varietiessuch as task-based some

...

velop this particular presentation so that readers rigid scholarssuggestnot [even] using Englishin a

could enter into the events studied and vicari- class.So, I am at a loss whatCLTis. I thinklanguage

ously participate in creating text (Eisner, 1991). teachingshould be related to students'experiences

Instead of talking about qualitative data, here it is and interests whichcreatenaturalsituations them

for

actually presented.4 to speak.I supposeit is important,but I don't know

whetherit is communicative not. (Yumiko)

or

CLT:PRACTICALUNDERSTANDINGS Four main conceptions about CLT were dis-

cussed by the teachers: (a) CLT is learning to

In this section, we bring together data from communicate in the L2, (b) CLT uses mainly

interviews, surveys, and observations to describe speaking and listening, (c) CLT involves little

teachers' beliefs, knowledge, and prac- grammar instruction, (d) CLT uses (time-con-

tices-their understandings-of CLT. In the first suming) activities. How teachers talked about and

part, we outline the salient issues they conveyed defined their notions of CLT were developed

in the interviews and responded to on their sur- through these four main conceptions that were](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cltinpractice-130226135546-phpapp01/75/Clt-in-practice-9-2048.jpg)

![502 The ModernLanguageJournal83 (1999)

revealed through LOTE (Japanese) teachers' 1989; Koide, 1976; Lange, 1982] and became par-

voices, responses, and actions. ticularly highlighted when foreign language or

LOTE instruction spread to primary schools

CLTIsLearningto Communicate theL2. Almost

in

[Clyne, 1977; Heining-Boynton, 1990]). The

all teachers globally defined CLT as learning to

teachers relayed their frustrations when discuss-

communicate with other people using the L2. A

few specifically added to that definition the idea ing these problems with (communicative) lan-

of using language for real purposes. Participants guage teaching.

As Japanese language teaching and learning

relayed their sentiments as the following teachers became popular (and required) in primary

did.

schools, these high school teachers faced articu-

I would hope that I would, ought to teach students lation problems. Alicia described how the teach-

how to communicate both orally and in a written ers did not necessarily welcome previous lan-

form so that I would expect them to hold a conversa- guage learning experiences by their students in

tion at the best of their ability. (Debra) primary schools. Tracey maintained that LOTE

It's teaching language that can be used by students in

teaching needed to be accepted and supported

real life, in real life-like situations. It's used for real within the school and wider community, and Yu-

purposes. There must be some need to communicate miko yearned for collegiality.

in order to be able to challenge the students to use

language communicatively. (Joan) I think the most difficult thing is [the] students com-

Learning to communicate was an important ing from [the] primary school. Some of them maybe

attribute of CLT, and, through the survey, these have 3 years, and some of them maybe have 1 year in

teachers agreed that the students' motivation to primary school, some of them have nothing. Then,

continue language study was directly related to they're coming to Year 8. And it's very difficult to

have the mixed classes. Then, when you're getting to

their success in actually learning to speak the

Year 9, you have students who are coming to doJapa-

language. They also suggested that students did nese in Year 9, who have no Japanese, who have

not have to answer a question posed in Japanese various experiences [and you start] all over again.

with a complete sentence and strongly agreed (Alicia)

that one could not teach language without cul- Another issue is at the moment, we're in [a] real

ture, while concurring that cultural information transition period in the community with acceptance

should be given in the L2 as much as possible. and nonacceptance of LOTE teaching as valuable.

These teachers were clearly aware that simulated Some people value it, some people don't value it at

all. And some of the people in the community don't

real-life situations should be used to teach conver-

value it, or colleagues [within the school don't value

sational skills, yet were ultimately realistic in

it either]. So that's very difficult until we have a cul-

agreeing that most language classes did not pro- ture of, no, not a culture of, uh, a mindset, where

vide enough opportunity for the development of

having a second language is valuable. That's the be-

such conversational skills. It is clear that teachers ginning and the end. Learning all languages is valu-

saw the value in what CLT offered; nonetheless, able. That's it. So you learn it all through primary

their scepticism about attaining communicative [school], secondary [school]. It's exactly the same,

skills surfaced. The participants neither agreed science, English, math you do it. It's just part of what

nor disagreed that the ability to speak a language you do. But we are not there yet. So until we get to

was innate; therefore, they believed that everyone that point, this transition is very difficult. We have an

opposition from others. (Tracey)

capable of speaking a first language should be I also feel it's difficult to receive support from the

capable of learning to speak a L2. Although there school just because I'm not Australian. I think it's

was the potential for communication in their

true. We don't usually communicate with other col-

classrooms, the teachers were unsure about the leagues. We talk to each other only within close

extent to which they had the time to promote it friends. Though it's not related to language teaching

and whether or not all students were capable of directly, I think it is a problem. (Yumiko)

learning it.

Three challenges created further tensions for On the survey the LOTE teachers as a group

teachers in promoting communication in the L2. neither agreed nor disagreed that they needed to

These included subject matter articulation, lack be fluent themselves to begin to teach communi-

of institutional support, and their own lack of catively. Nonetheless, during the interviews, the

proficiency in the L2. (These three issues have teachers commented on their own (inadequate)

plagued the language professions in both Austra- language proficiency; however, many reported

lia and the U.S. [e.g., Ariew, 1982; Australian Lan- that they tried to use the L2 as much as possible.

guage and Literacy Council, 1996; Kawagoe, Tamara felt insecure about her language profi-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cltinpractice-130226135546-phpapp01/75/Clt-in-practice-10-2048.jpg)

![Sato and RobertC. Kleinsasser

Kazuyoshi 503

ciency. Joan responded that, as she became more ing. In short, her L2 learning experiences

confident with her L2 proficiency and ability to seemed to have formed a belief that CLT used

meet students' needs, she moved further away only speaking and listening.

from the textbook. Tamara was not afraid to be The survey results reinforced the significance

honest. Joan decided to go back to university to of speaking and listening skills, or at least sug-

finish her 3rd year of Japanese study. gested that there might be an order to how skills

were learned. The teachers agreed that the in-

Also, my ability to speak Japanese. Sometimes I feel struction of such skills preceded the teaching of

like my language is not sufficient to challenge the

students, to push them. I don't think I give them reading and writing, that L2 acquisition was most

successful when based on an oral approach, and

enough listening experience, because I am insecure

of my ownJapanese. (Tamara) that students could still be successful in learning

In terms of the daily use of textbook, I am surprised to communicate in a L2 even if they did not read

to find that I am moving further and further away well. The teachers did not attribute weak oral

from [the] use of the regular textbook. Every year competence to a lack of objective means in teach-

level has one, but I find as I become more confident ing it. Nonetheless, assessment of students' lan-

with my language, and as I become more confident to

guage abilities caused some concern.

meet the needs or interest of the students and differ- The LOTE teachers found that assessment

ent topics, I want real Japanese language, not the

tasks that were focused on the four skills offered

textbook. (oan)

another slight obstacle. It is interesting to note

The teachers reported that CLT meant learn- that the LOTE teachers emphasized that CLT

ing to communicate in the L2. The interview and meant speaking and listening; however, the gov-

survey data showed how they coped with what this ernment guidelines for communicative assess-

meant to them. The challenges, however, seemed ment included all four skills, each seemingly

sometimes to outweigh the benefits of making given equal weighting. The teachers' concerns

communication in the L2 a reality. Nonetheless, dealt with the number of tests and the lack of

the first conception served as a general reminder cohesion among the skill examinations.

about the global purpose of CLT. This focus on

And we have four tests at the end of each semester,

communication led to the second conception

reading, writing, listening, and speaking. And the

that these teachers think writing and reading are middle of each semester, we have two tests. In the

not as prevalent (important) as listening and middle of [the] first semester, if we test reading and

speaking. writing, then, in the middle of [the] second semester,

we test speaking and listening. So by the end of the

CLT Uses Mainly Speakingand Listening.A sec- year we've tested four skills, three times. (Margaret)

ond trend from the data revealed that several Well, according to the senior curriculum, I am re-

teachers viewed CLT as focusing extensively on quired to give them a certain number of tests in what

speaking and listening skills. The following they call the four macro skills-reading, writing,

quotes represented this general view. speaking, and listening. They all have to be separate

tests. So I have to give them one of each kind of tests

The goal of the teaching is that at the end of learning each term. I basicallyjust give them tests, you know. I

the language, people can actually talk in the language will have a passage written in Japanese on a topic that

with the native speakers understand [ing] what we've studied. And they have to read it and they have

they're saying and be [ing] able to communicate their questions in English and they have to answer in En-

ideas rather than just being able to read and write. glish. So it's just as a comprehensive test. Listening,

(Margaret) well, I'll have [a] passage in Japanese. I'll read it and

My understanding of CLT is that you teach so that then they'll have questions in English. So they don't

[the] students hear it and so that they speak it. I see it. Theyjust think they read it. Then, they have to

would try where it's possible to teach something new answer in English. And speaking, I just give them

by actually speaking. [...] I think writing needs a little some topics to talk about and they have to talk. (Role

explanation to teach the pattern and get them to play or interview?) Oh, both. So, that's how I evalu-

write the pattern. [. . .] And perhaps because I ate, just standard, four micro skills tests. I'm not par-

learned Japanese as an adult and learned it commu- ticularly looking for communicative skills as such, but

nicatively, I didn't learn a lot of writing at the time. just as four micro skills, which is the prescribed way

Writing was the neglected skill. So I suppose I've been of testing. (Sean)

very aware of CLT. (Alicia)

The tension between CLT and skills became

At the completion of her interview, Alicia re- apparent. The teachers saw two completely differ-

vealed again that she learnedJapanese communi- ent issues and proceeded with what they per-

catively in speaking and listening, but not in writ- ceived they had to do in their classrooms for their](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cltinpractice-130226135546-phpapp01/75/Clt-in-practice-11-2048.jpg)

![504 The Modern Language Journal 83 (1999)

students. It is interesting to note that many of nation. So that's why I like [a] combination of both

them did not see, or present, how the competing systems. (Jane)

conceptions could be reconciled. They allowed Debra was in a dilemma, because she was not

their understanding of skills (through policy) to

allowed to offer a grammar test according to the

outweigh their promotion of CLT (especially in government's guidelines of communicative as-

using speaking and listening). Items from the sessment.

survey further revealed that the group thought

that dialogue memorization was an effective tech- I think that [the] writing test is the main worry. It is

the big worry, because it takes us a lot of time. Actu-

nique in the process of learning a L2 but dis-

agreed over the belief that mastering L2 gram- ally this is the big problem with CLT,because our tests

have to be communicative, too. So we can't have a

mar was a prerequisite to developing oral

communication skills. This disagreement could grammar test. We can't have a test where you have to

do multiple choice. No, we can't. We can't do it at all.

be why some teachers saw these other skills (read- So what we have to do is trying authentic material for

ing and writing) as a means to focus on grammar. students to read. (Debra)

These issues and challenges only seemed to rein-

force the third conception about the role of The participants were challenged over what to

in CLT. do with grammar in their learning environments.

grammar

Most teachers did not discuss the role of gram-

mar in CLT because they thought grammar was

CLT Involves Little Grammar Instruction. Quite a

not part of CLT. Neither did they understand

few teachers understood CLT as not involving

completely the guidelines for not allowing gram-

grammar, or any type of language structure. Al-

mar to be included in their testing. Yet they re-

though some teachers did not directly mention

layed difficulties in teaching it when it came to

grammar usage, many alluded to the problem of

how, if at all, to include it. discussing what went on with language teaching

in their classrooms. Although some did not know

Another issue in LOTE learning and teaching is that the role of grammar in CLT as revealed in the

"Is communicative teaching good?" Because people definitions above, others blamed English teach-

have taken it so far to the point of the banning of ers for not teaching grammar or felt it difficult to

grammar teaching or of the banning of drilling, of present grammar in an interesting way, or both.

the banning of all little parts. You have to do at some

points, to learn Hiragana [apanese syllabary], you Uh, these are difficult questions. What's the role of

have to write out over and over after practice. But in grammar? Uh, I think grammar is important so that

communicative language, you think, "Ican't do it. It's meaning is not lost, but I try not to correct the stu-

not communicative." So that's the burden. ... So dents' grammar too much, when they speak, because

when I [was] first teaching grammar, it had very little, I don't want to inhibit them. I don't think it is [a] very

very little place. We did lots of talking, lots of reading important thing. I treat it as a building block, and

and writing and listening, but not so much grammar. then, hopefully that will make students practice what-

Which is the mistake of, I think, part of the flow in ever language they've learned before. And if there

communicative teaching. I almost expected that stu- are many minor mistakes on grammar, I don't fix

dents would pick it up. They would somehow work it them up on it. Yeah, I can't answer that question very

out without me saying "'wo' is the object.... It well. (Tamara)

would work if you guess. Sometimes I still do that. For a number of years now, they haven't really been

(Tracey) teaching even in English very much. I found a lot of

It's using Japanese whenever possible in the class- my students at high school don't really know much

room. But I'm not particularly a communicative lan- about the technical aspects of English language. So it

was discouraged for some years. The teaching of En-

guage teacher, because I love teaching grammar....

While I like some aspects of it, I very much dislike glish grammar was discouraged. So a lot of the stu-

some ... aspects of it... while I was studying inJapan, dents have gone through the high school system not

I had a teacher who was studying [the] communica- really learning English grammar. So then, you know,

tive method. And she believed that she did not ex- I think it's unfortunate. So it's hard to teach them

plain grammatical points in the text. She believed you Japanese grammar if they don't understand English

should get to understand them from the atmosphere. grammar. (Sean)

And that was very frustrating as a student. So that's

The conundrum of grammar's place within

why I don't like it so much, because I love to under- CLT (or language teaching in general, for that

stand the grammar. And I think many of the best

students do. And students we have doing Japanese matter) was further highlighted in the survey re-

are often very analytical thinkers. AndJapanese to me sults. As a group, these teachers were uncertain

is a little bit like math. And students thought of it like about the importance of having students learn

math. So sometimes it's possible to have a little expla- rules of grammar (they neither agreed nor dis-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cltinpractice-130226135546-phpapp01/75/Clt-in-practice-12-2048.jpg)

![Sato and RobertC. Kleinsasser

Kazuyoshi 505

agreed) but were adamant that the grammar- Then, we give them ... extrathingsthey can add to

translation approach to L2 learning was not effec- it. Then, theymustlearnand presentit in a class.Do

tive in developing oral communication skills. On role-play or so. And in Year9 [it is] similar, but there's

more freedom. By the time you get to Year 12, just

the one hand, these LOTE teachers accepted that

talk. (Laura)

student responses in the L2 did not have to be

linguistically accurate. They further agreed that

when a student made syntactical errors, the er- WhatJapanese LanguageTeachers Did: Traditional

rors should be accepted as a natural and inevita- Practices.Regardless of the role grammar had ac-

ble part of language acquisition and that ideas cording to the individual teachers or what teach-

can be exchanged spontaneously in a foreign lan- ers said about accommodating learning styles,

guage without having linguistic accuracy. On the many findings from classroom observations con-

other hand, the LOTE teachers agreed that if first founded the information given by the teachers in

language (L1) teachers taught grammar the way their interviews and on their surveys. Grammar

they should, it would be easier for them to teach was more central in their language teaching than

a L2. The participants further agreed that when these LOTE teachers admitted. The teachers

the foreign language structure differed from that were more didactic in their instruction than they

of the LI, sometimes extensive repetitions, sim- related and less concerned with individuals than

ple and varied, were needed to form the new with the class as a group entity. Whether or not

habit. They agreed that pattern practice was an they were teaching communicatively, grammar

effective learning technique and that the estab- was a central focus in the observed classrooms.

lishment of new language habits required exten- For example, although most teachers said that

sive, well-planned practice on a limited body of they used role-play, games, simulations, and so

vocabulary and sentence patterns. on, classes observed for this study were heavily

It is interesting to note that puzzlement over teacher-fronted, grammar was presented without

issues surrounding grammar also manifested it- any context clues, and there were few interactions

self within another challenge teachers had with seen among students in the classrooms (this de-

learning styles. Most teachers acknowledged that scribes what we mean by "traditional practices").

they had to be aware of students' learning styles, Most Japanese teachers used English extensively

especially different styles between year levels. to explain grammatical points and give instruc-

They tended to agree with the survey item that all tions; L2 communicative use and speaking in the

students, regardless of previous academic success L2 by students, in particular, were not as preva-

and preparation, should be encouraged and lent as one might assume from listening to the

given the opportunity to study a foreign lan- interviews or reading the survey results. TheJapa-

guage. Nonetheless, learning styles offered an ad- nese teachers readily allowed students to answer

ditional focus that some felt was not at all part of in English. A few teachers tried to integrate cul-

CLT. Moreover, here teachers related that some ture into their lessons. In short, most teachers

students wanted a grammar focus.

displayed traditional practice tendencies. The fol-

All Grade11 and 12 wantto studyin a formalway.So lowing selected examples typicallyportrayed what

was seen in the Japanese language classrooms.

even though I introduce a communicative activity, For instance, Tamara started her lesson for

they don't want to get involvedin it. They are more

interestedin grammatical Year 12 with a Kanji (Chinese characters) quiz.

explanations.But, for ex-

ample,Grade10 get along well with me. They really

like interestingtopics and start to speak. So I feel At the beginning, she handed out quiz sheets to eve-

more comfortable juniors.Seniorsseem to have

with ryone. She gave students 10 minutes to complete the

acquireda formalwayof studyinglikeJapanesestu- quiz. While students were working on the quiz, she

dents .. .This is where the difficulty lies, I feel. (Yu- wrote grammatical points on the board. After the

miko) quiz, she started to explain the grammar (passive

Uh, Year 8, they learn patterns. We teach them, you form) by using English sentences as examples. Then,

know, 'This is the pattern." If you want to say, I like she explained it with Japanese sentences. While she

French and I like math, and I hate science. Then, we explained verb conjugations, students wrote them

teach them to say, ". . . ga suki," ". . . ga kirai desu." down in their notebooks. After that, she showed verb

Then, we give them a list of subjects. And we get them cards and made students say passive forms. It was like

to talk. So they can express their own feeling inJapa- drills. Then, she asked students to open the text-

nese. We did the same things with sports and hobbies books, and they did exercises that transformed active

and families.... And then, if we are doing something sentences into passive ones. She called on each stu-

like [the topic of] restaurant, then, we give them a dent individually and let him or her answer. Finally,

dialogue. We get them to learn the basic dialogue. she asked students to create their own sentences by](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cltinpractice-130226135546-phpapp01/75/Clt-in-practice-13-2048.jpg)

![Kazuyoshi Sato and Robert C. Kleinsasser 507

It's from CLT or I'm not sure where it comes from. exercise. But I don't teach from the textbook, usually

But there is an understanding that as LOTE teachers I teach something new, before they look at the text-

we must have our classes, [they] must be fun, they book. So we need more time to prepare our own

must be entertaining, and so [we] play lots of games materials. It's quite hard. It's not like Japan where

and kill ourselves trying to entertain our students. If they use, everybody uses the same, and same day,

they are not, if it is not entertaining, we feel like we're same page.... I think I need time to prepare the

failing. And students also [say], 'That's boring, Miss." resources for the students. I think that's really impor-

And you think, of course, everything has some bor- tant. To make flash cards, to make the lesson interest-

ing, bad, some not interesting parts, right? So that's ing, we need to have really more time. (Debra)

another part. (Tracey) The time to reflect as a teacher. [... ] And I teach 27

My understanding of communicative teaching is, I out of 35 lessons a week. [... ] I might have three or

suppose, teaching in a way rather than just learn [ing] four lessons a week at most of my own preparation

grammar or translat[ing] from one language to an- and correction time. What I would really love is the

other. It involves using learning activities where the luxury of something like a position, a head of Depart-

students are actually engaged in communicating with ment, where you have [a] half time table, half teach-

other people, of course, usually within [a] class ing, half managing, where you would have time to

group.... In that way, I suppose, they are supposed look at resource materials available and slowly and

to learn how to use the language more easily than just carefully put together a course. (Joan)

to try [the] grammatical translation [way] to learn-

ing.... But I have not really used them very much. Another major challenge to CLT and its activi-

Well, it's time-consuming. Of course, it's so much ties was discipline. Margaret revealed in her inter-

easier to use [a] textbook. I mean it would be nicer if view that discipline was the priority and that there

it was a textbook with a lot of communicative learning was little room for her to use communicative ac-

activities in it. To be always making every week, for tivities in Grade 8 classes. Jane also used a similar

every lesson, to make activities in it, it's very time-con-

technique to "settle students down."

suming and [I] just wonder, I don't have that much

time to spend on it. Because I have other subjects and But unfortunately a lot of our students, lots of stu-

another class to teach, too. (Sean) dents I am teaching at high school at Year 8, they are

forced to studyJapanese. So they have very negative

Quite a few participants said they occasionally

attitudes. So if I speak to them in Japanese in the

used CLT activities in classrooms. Alicia described

classroom, they switch off from what they want to

her use of a fun activity. know. So all of the time I have to speak in English

So you can use group activities or pair activities, inter- anyway. And they are quite badly behaved students

views, they can be interviewing. For instance, another anyway.So the way that I teach Japanese is not really

communicative. It's more like I've got to keep these

thing the Year 10 just learned is to say when is your

kids quiet, more behaved for 35 minutes. And the

birthday. So they have to go around and ask 10 peo-

main idea is not that I'm teaching at all. The main

ple that question.... So that's communication. They

can go around and ask. This school is very interest- idea is discipline. (Margaret)

ing. Hardly anybody was born in [suburb]. So I use Nearly everyday I give them a little quiz to start with

activities like that as often as I can. And then also for the lesson, quite often. And it might be grammar or

listening, for instance, today, with one of my Year 10 vocabulary or Kanji or something. Almost everyday,

classes, I was pretending to be their phone answering particularlywith Grade 8, it settles them down. If they

machine. I'm the answering machine. So they had to write something, they can concentrate on it. (Jane)

take notes. So I pretended to be the person. So I

made suggestions. (Alicia) Although LOTE teachers agreed that language

learning should be fun, they disagreed that L2

Almost all teachers reported they needed more acquisition was not and probably never would be

time to prepare materials for CLT activities, relevant to the average Australian student. But

which related directly to the fact that these teach- they neither agreed nor disagreed as a group that

ers perceived there existed a lack of good materi- one of their problems in teaching a L2 was that

als including textbooks for communicative lan- they tried to make learning fun and games. Some

guage instruction. teachers agreed, others disagreed, and there was

no consensus.

We don't use the textbook everyday.My Grade 8, they

have no textbook. Next year we'll have one, but this Yet, student motivation and LOTE teachers'

concerns about it appeared throughout the inter-

year we don't, because the textbook was not commu-

nicative. It was too boring. For Grade 9 we have Is- views. As seen in previous quotations and discus-

shoni just for the first time this year. So I use this sions, these teachers struggled to motivate their

perhaps half of the time. So after four lessons maybe students. This particular issue gained momentum

I'll use it for part of the lessons. And then, we'll use when the teachers admitted to their difficulties

this to practice. And they can use this for a homework with subject matter articulation, grammar in-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cltinpractice-130226135546-phpapp01/75/Clt-in-practice-15-2048.jpg)

![508 The Modern LanguageJournal 83 (1999)

struction, acknowledgment of individual learn- music, then, they can read a music magazine or watch

the video clip, or [sing] some Japanese songs or

ing styles, and questionable assessment items. Stu-

dent motivation also affected the decision on something like that. And that makes them more in-

terested. (Debra)

whether or not to try out CLT.Jane expressed her

difficulty in motivating students who, especially in CLT activities appeared, at first glance, to influ-

Grade 8, had to take the subject. Note further ence student motivation, but this was not neces-

that she again highlighted and integrally related sarily the case. Instead, their focus on form and

the issue of learning styles. student discipline made these teachers shy away

from CLT activities, or relegate them to the more

The most critical issue at the junior level is that be-

advanced language learners. Moreover, it ap-

cause they are not streamed academically, we have [a]

very wide range of ability from very good to very poor peared that the lack of availability of CLT activi-

[students in the] language class we have today. And ties (or time to create them) caused these teach-

so we must teach "Hiragana."But some students can't ers practically to ignore them. Time was not what

master that. So they are already dropping behind. So these teachers had, so CLT activities were not a

by the end of the year, there's a very wide gap. And priority. This low priority was apparent in the

those students who are very poor become very resent-

scarcity of CLT activities (of any kind) seen dur-

ful. And it's very hard to maintain the interest level of

ing observations.

everyone, when there's such a wide gap. So that's one

of the most critical issues. And I don't know what the What Japanese Language TeachersDid: Innovative

answer is, we should stream or what we should do. But Practices. It was obvious that the teachers believed

that also subtracts from CLT,because, of course, they that CLT activities created too much work for

can't understand. They're slower learners. So they

them, because few participants were observed to

can't write, they can't stand what is happening as well

use such activities in the classroom. In contrast to

as the better students. So that's one of the most criti-

their use of the traditional practices mentioned

cal issues. (Jane)

previously, only a few teachers used student-stu-

Tamara revisited the value of learning another dent interactions or made students use the lan-

language: guage for real purposes. Of these, two teachers

also attempted to use Japanese to a greater extent

And also I think it important that students see a value

than the other teachers did. As mentioned above,

in learning another language, because if they don't

Alicia reported using some innovative ideas. Her

see it as just another subject that they have to do, I

don't think we're going to have a right attitude to lesson for Year 9 gave further insight into her

learning about cultures. And if they are not inter- practices.

ested in culture, then, it's also going to make it diffi-

First, she reviewed some Kanji numbers. She held

cult for them to pick up the language. (Tamara)

cards and asked each student to read one. The stu-

Debra lamented the fact that students lacked dent picked up the card. She told the student inJapa-

nese to show the card to everyone. Others repeated

motivation because they did not particularly care

the number. She tried several cards. All these words

for discrete-point learning:

were related to the topic "restaurant." Then, she

I think sometimes, [students] lack the motivation to showed a Japanese tea cup, a sake cup, and other

really study a language, the skills of the language. For things asking questions in Japanese. Students an-

swered in Japanese. She checked homework. Those

example, I can teach them some new words or new

who did not do the homework stood up, and they

Kanji, but students find it very hard to learn. The

students must realize that they need to study. And, of were told to come back to the classroom during

course, if they had a trip toJapan, that would be good lunchtime to show the homework. Then, they did

motivation for them. (Debra) translation exercises from the textbook. After giving

instruction for the next homework assignment, she

Debra did encourage students in Years 11 and gave students 10 minutes to prepare for a role-play (at

12 to involve themselves in theJapanese language the Japanese restaurant) in groups of 3 to 4. One stu-

dent was a waiter/waitress, and the others were cus-

by watching TV programs and reading. These

activities would, she felt, encourage the students tomers. She walked around the class and sometimes

to be motivated to learn in her advanced classes. answered students' questions. Then, four groups per-

formed in front of the class. Three groups mainly fol-

And I'm trying to build up the materials that we have lowed the model dialogue, but the last group was in-

at school so that students can be interested in the teresting because the students did not follow the

subject. So, for example, if we have students in class, model dialogue. They made the class laugh. She made

who are interested in sports, they can read some some comments on their performance-"Well done"

sporting magazine, so [we] watch the baseball or and a little tip about how to order at aJapanese restau-

Sumo on TV. Or if the students are interested in rant. (Observation of Alicia)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cltinpractice-130226135546-phpapp01/75/Clt-in-practice-16-2048.jpg)

![510 TheModernLanguageJournal 83 (1999)

tional practices: teacher-fronted, repetition, is less than it should be, because I don't want them to

translation, explicit grammar presentation, prac- feel put down. So that impacts as well. (Tracey)

tice from the textbook, and little or no L2 use or

culture integration. Their conceptions of CLT PersonalL2 Teaching:The Significance

appeared to have little chance for extensive devel- of Trial and Error

opment. Furthermore, their L2 instructional be-

liefs, knowledge, and practices were rarely guided The teachers also learned about CLT by teaching;

that is, experience in actually teaching Japanese

by their conceptions of CLT.

We examine next how these LOTE teachers taught them about what they perceived as commu-

nicative possibilities. They described how they

thought they learned about CLT and reveal how

they personally made sense of Japanese teaching gained this knowledge through trial and error.

and learning. The following section unravels just I learned about CLT when I became a teacher, be-

how teachers thought they developed their ideas cause I don't have any language training. So, apart

about CLT. from experiences teaching English in Japan, I didn't

have much language teaching methodology at all. So

I think I've done a lot of learning in the last couple

HOWJAPANESE LANGUAGE TEACHERS of years about how to write an assessment item. So

LEARNED ABOUT CLT

that's real experience from the students rather than

As the teachers discussed their various ideas something really theoretical. Yes, so trial and error.

about CLT, they were also asked how they learned (Tamara)

But also I think you learn by trial and error, trying

about CLT, how they came to hold these concep-

something. And if it doesn't work, you change it so

tions of CLT, and what their sources of learning that it will be suitable in the situation. (Alicia)

were. Responses from the interviews showed that I think, initially when I started teaching, I did try to

the teachers learned about CLT from a variety of some extent to use [the] communicative language

things that included personal L2 learning, per- method, but I'm afraid of, [the lack of a] period of

sonal L2 teaching (trial and error), teacher devel- time, especially this year, when I have virtually no

opment programs, inservices, and other teachers. students with [a] higher motivation level to study

Although the teachers learned about CLT Japanese. Maybe one or two at most. I'm afraid, I

haven't put much energy into it in developing [a]

through multiple avenues, personal L2 learning

communicative style in normal activities .... But I

and teaching experiences seemed to have had the

must admit, I suppose, when I did try to use that type

greatest influence. of activity,students are more enthusiastic about study-

ing. I think that's true. They attempted, particularly

PersonalL2 Learning younger students, liked to play games rather than

engaging in formal lessons, you know. But again, you

How teachers learned L2s as students seemed know, most of them are not really interested in learn-

to influence heavily their beliefs about language ingJapanese anyway.So for them, they would rather

teaching and, hence, their personal views about play anything, sorts of games than do any sorts of

CLT. In particular, those who learned L2 in real formal study, whether it will be Japanese or any other

situations had strong beliefs about how students subjects, you know. They are not, on the whole, aca-

learn a L2. demically oriented students in my class, very few, par-

ticularlyJapanese classes. (Sean)

In high school I learned French and I learned French

It became evident from the teachers' com-

not in a communicative way at all. I learned French

rather like Japanese students in Japan learning En- ments that they perceived both the negative and

glish. So that was not very much help. When I learned positive sides of trial and error learning and

Japanese in university, I did so much, so much trans- teaching with CLT ideas and concepts. This am-

lation and that was not really communicative. I think, bivalence was further reinforced with interview

when I went out becoming a student teacher and I and observation data; the teachers spoke about

watched other teachers teach Japanese, and then, the numerous challenges they faced and how

after that it's just talking to other teachers and just

they found it more prudent to implement tradi-

learning, keep learning. How I teach is very personal tional practices over innovative ones.

and I teach every class in a different way. (Debra)

My own LOTE learning history affects, of course, how

I learn. I think. That's effective for me. And I say my Teacher

Development,InservicePrograms,

preferences. Oh, yeah, another thing is my beliefs and OtherTeachers

about kids and how they learn. I feel that kids feel

embarrassed, they don't want to keep trying, so I try The teachers spoke about learning from these

not to embarrass them. Perhaps my error-correction three sources. Nonetheless, the majority of the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cltinpractice-130226135546-phpapp01/75/Clt-in-practice-18-2048.jpg)

![KazuyoshiSato and RobertC. Kleinsasser 511

LOTE teachers, most of the time, would always watching good and bad teachers and learning

digress to how they relied upon themselves and about their experiences was quite influential.

their experiences as described above. They ac-

I was teaching Japanese without having any training

knowledged these sources, yet in the wider inter- at all in teaching a foreign language. And the other

views, it appeared that their own beliefs filtered teachers on the staff helped me. And I started to go

what these sources offered, and the context of to inservice trainings, seminars, and I enrolled in a

their own teaching seemed to determine what course for 1 year at the University of [name]. It was

they would use from the sources. What they supposed to be the course about how to teach Japa-

picked up is offered next. nese, but it was also to upgradeJapanese language. A

The four LOTE (Japanese) teachers who re- lot of it wasn't actually how to teach Japanese, but it

ceived Postgraduate Diplomas of Education were was still a good course. (Is the teacher Ms. [name]?)

initially exposed to CLT in teacher development Yes, she is a good teacher. Ms. [name] showed the

model of communicative method in her teaching

programs, and the others spoke of inservice in-

volvement. (Note that because about half of the style. I was able to see what [a] communicative lan-

guage teacher was supposed to be like. So I could see

participants had little to no LOTE teacher educa- how I should be teaching. (Margaret)

tion involvement, inservices were one way of in- I think over the years, you see good teachers and you

creasing their knowledge). see bad teachers. And you develop your own methods

Communicative language teaching was the style of according to what you see. So I learn more by exam-

teaching that they favored at the University of ple than I learn by reading a book. And of course, we

must always adapt to the environment that we're

[name], when I studied [the] Diploma of Education.

So everything was supposed to be aimed at develop- teaching in. You know, that students in every school

differ and you must adapt your methodology to suit

ing communicative language teaching skills. (Sean)

I learned about CLT at a Postgraduate Diploma of the students where you are. (Jane)

Education course at the University of [name] last

year. It was like a cram school. So I actually learned

when I did my teaching practice at a high school. Summary

(Yumiko) The way that these teachers made sense of

Teachers who attended a teacher development their L2 teaching and learning was based on

course gained some ideas about CLT but did not their personal experiences; little that we found

seem to have very thorough explanations of what showed development of their approach within

CLT meant. The teachers who attended inser- any type of program or inservice. Although the

vices related that they had difficulties finding the teachers said they learned about CLT from oth-

time necessary to implement the classroom activi- ers by attending teacher development programs

ties that they learned there. and inservices and by watching other teachers,

personal L2 learning and teaching experiences

So I think most inservices are giving us techniques filtered through as the primary variables that

which are really encouraging students to use the lan-

nurtured their beliefs, knowledge, and practices

guage they know and encourage them to learn from in L2 teaching and learning. It is interesting to

each other. Yeah, they are not teacher-oriented. It's

more group work-oriented and interaction. But every note that these personal experiences seemed to

time I go to inservices, I think, "Oh, I should use this. lead to more global beliefs about what they per-

I should use that." And then, sometimes when I get ceived as L2 teaching and learning, and those

back to school, I just don't have the time to plan all beliefs did not necessarily include CLT. In the

those things. (Tamara) final analysis, the teachers were reluctant to give

much credibility to what other teachers or lec-

One teacher lamented the fact that she could

turers said. In this study, our attention was fo-

not go to a workshop while school was in session.

cused on how these teachers developed their

These days we can't go in school time. It's terrible. own personal understandings within their teach-

And it was so busy after school. So I haven't been to ing and learning situations and through their

any workshops at all. There was one that I was invited individual beliefs. There was a tendency for

to after school, but it was only discussing exam pa-

some teachers to rely on what they thought they

pers. It wasn't a workshop. From the [region], they saw some teachers in various classrooms do, and

haven't given any. There are some for beginning

teachers, but not for experienced teachers. (Jane) they rarely indicated that they discussed ideas,

notions, and perceptions concerning CLT with

Regardless of their preservice backgrounds, their colleagues or university classmates. The

the teachers found an additional source in other teachers in our group learned many lessons

teachers. In particular, the majority said that about L2 teaching from trial and error in their](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cltinpractice-130226135546-phpapp01/75/Clt-in-practice-19-2048.jpg)

![Kazuyoshi Sato and Robert C. Kleinsasser 517

mary. Journal of Japanese Language Teaching, 45, in communicative languageteaching Reading, MA:

II.

105-106. Addison Wesley.

Nunan, D. (1987). Communicative language teaching: Scarino, A., Vale, D., McKay,P., & Clark,J. (1988). Aus-

Making it work. ELTJournal,41, 136-145. tralian LanguageLevels(ALL)guidelines.Canberra,

Okazaki, H. (1996). Effects of a method course for pre- ACT, Australia: Curriculum Development Centre.

service teachers on beliefs on language learning. Schulz, R., & Bartz, W. (1975). Free to communicate. In

Journal ofJapaneseLanguage Teaching,89, 25-38. G. Jarvis (Ed.), Perspective: new freedom (pp.

A

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers' beliefs and educational 47-92). Skokie, IL: National Textbook Company.

research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Reviewof Senate. (1984). National languagepolicy.Canberra, ACT,

EducationalResearch, 307-332.

62, Australia: Australian Government Printing Ser-

Queensland Department of Education. (1989). In other vice.

words:A sourcebook language otherthan English,

for Shulman, L. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge

senior primary/junior secondary. Brisbane, QLD, growth in teaching. EducationalResearcher, (2),

15

Australia: QDE, Curriculum Development Ser- 4-14.

vices. Shulman, L. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Founda-

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (1986). Approaches and tions of the new reform. Harvard EducationalRe-

methods in language teaching. Cambridge: Cam- view,57, 1-22.

bridge University Press. Silverman, D. (1993). Interpreting qualitativedata:Methods

Richardson, V. (1990). Significant and worthwhile for analysing talk, text, and interaction. London:

change in teaching practice. EducationalResearcher, SAGE Publications.

19 (7), 10-18. Spradley, J. P. (1979). The ethnographic interview.New

Richardson, V. (1994). Conducting research on prac- York:Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

tice. EducationalResearcher, (5), 5-9.

23 StatView. (1993). Thesolutionfor data analysisand presen-

Richardson, V. (1996). The role of attitudes and beliefs tationgraphics[Computer software]. Berkeley, CA:

in learning to teach. In J. Sikula (Ed.), Handbook Abacus Concepts, Inc.

of research on teacher education (2nd ed., pp. Thompson, G. (1996). Some misconceptions about

102-119). New York: Simon & Schuster Macmil- communicative language teaching. ELT Journal,

lan. 50, 9-15.

Sato, K. (1997). Foreignlanguage teacher education:Teach- Vale, D., Scarino, A., & McKay, P. (1991). PocketALL.

ers'perceptions aboutcommunicative languageteaching Carlton, VIC, Australia: Curriculum Corporation.

and their practices. Unpublished masters' thesis, Van Maanen,J. (1988). Talesof thefield:On writingethnog-

University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia. raphy.Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Savignon, S. J. (1983). Communicative competence:Theory VanPatten, B. (Ed.). (1997). How language teaching is

and classroompractice. Reading, MA: Addison- constructed [special issue]. ModernLanguage Jour-

Wesley Longman. nal, 81.

Savignon, S.J. (1991). Communicative language teach- Wideen, M., Mayer-Smith,J., & Moon, B. (1998). A

ing: State of the art. TESOLQuarterly, 261-277.

25, critical analysis of the research on learning to

Savignon, S. J. (1997). Communicative competence:Theory teach: Making the case for an ecological perspec-

and classroom practice(2nd ed.). Sydney, NSW, Aus- tive on inquiry. Reviewof EducationalResearch,68,

tralia: McGraw-Hill. 130-178.

Savignon, S.J., & Berns, M. S. (Eds.). (1984). Initiatives Wenden, A. (1991). Learner strategies learnerautonomy.

for

in communicative language teaching.Reading, MA: Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Addison Wesley. Wolcott, H. F. (1990). Writingupqualitativeresearch. New-

Savignon, S.J., & Berns, M. S. (Eds.). (1987). Initiatives bury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Web Site for ACTFL Research SIG

The ACTFL Special Interest Group for Research announces their new Web site:

http://www.uiowa.edu/-actflsig/index.html

Look for paper sessions, poster sessions, and a business meeting at ACTFL Annual

Meetings. Proposals

for sessions are solicited.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cltinpractice-130226135546-phpapp01/75/Clt-in-practice-25-2048.jpg)