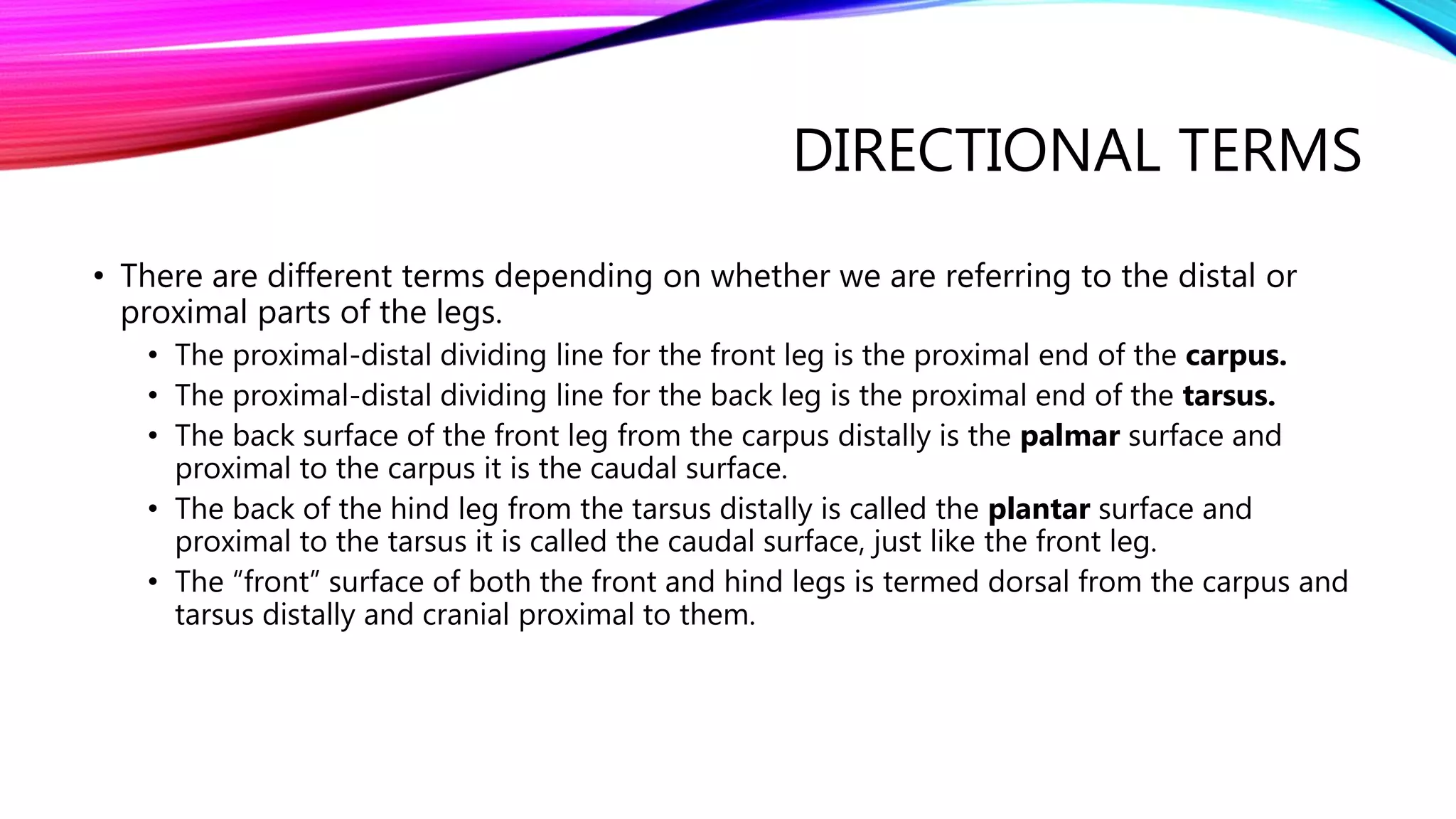

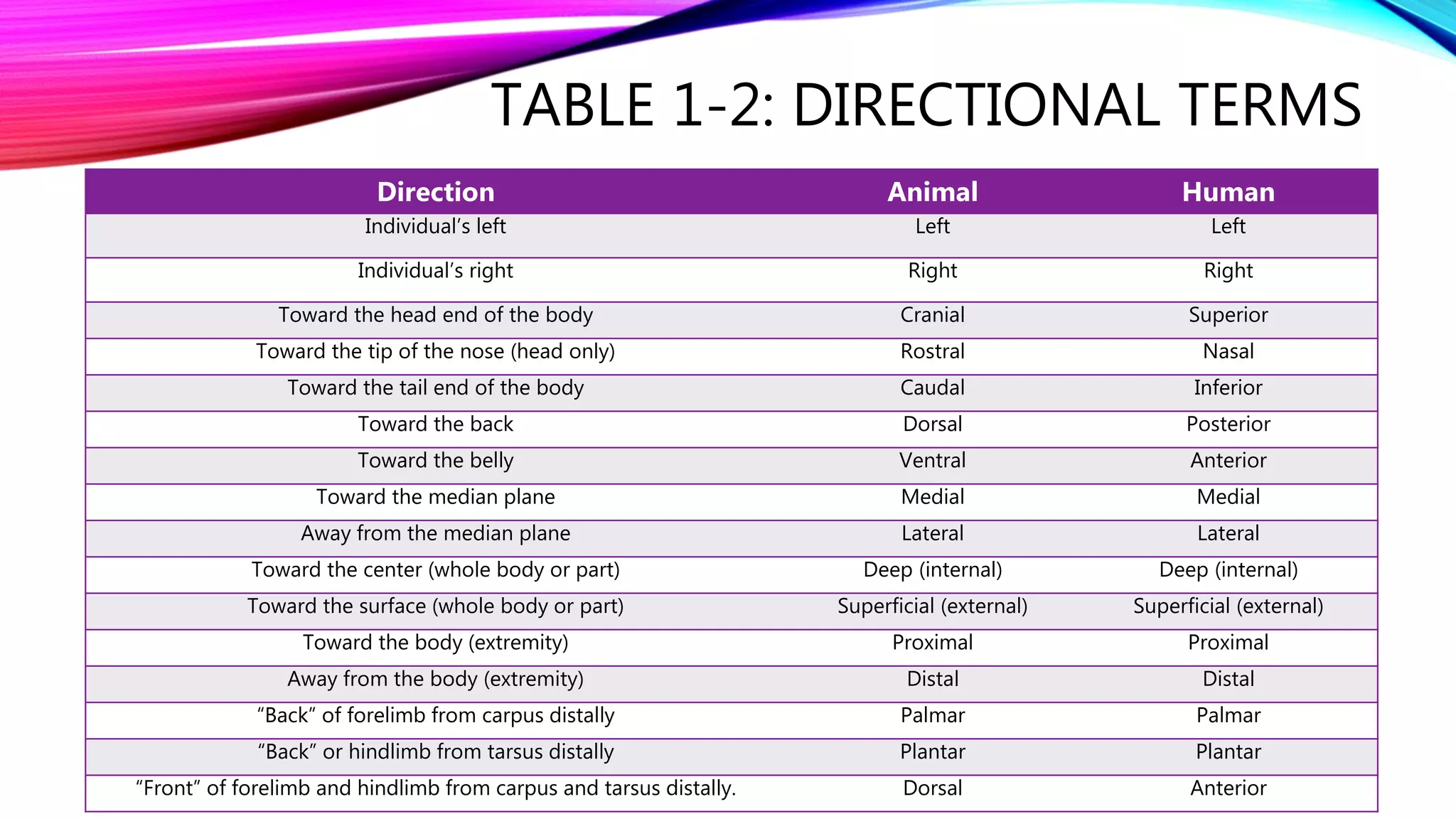

This document provides an introduction to veterinary anatomy and physiology. It discusses how understanding anatomy and physiology is important for veterinary professionals to understand how animals function and maintain health. It then defines anatomy and physiology, describing anatomy as the form and structure of the body and physiology as the functions of the body. The document goes on to discuss the main body systems, anatomical terminology including planes of reference and directional terms, tissues, cells and organs.