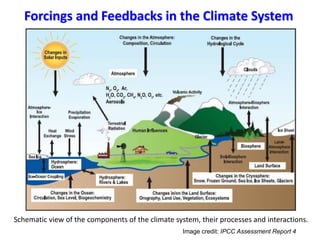

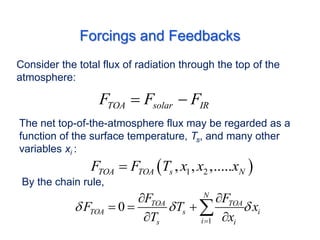

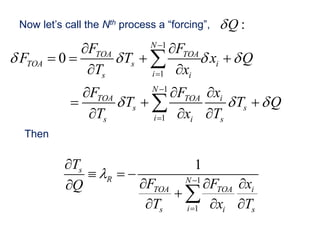

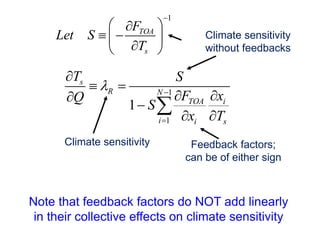

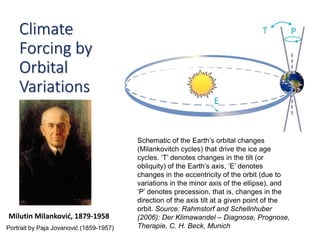

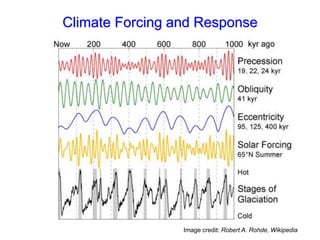

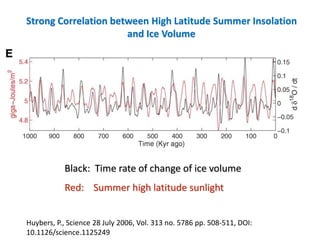

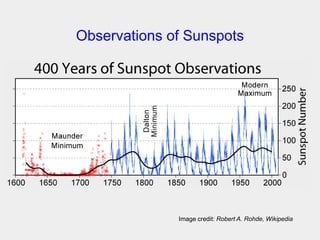

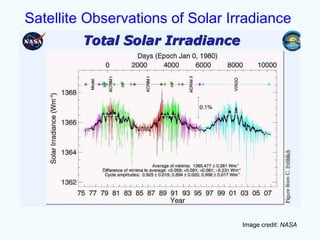

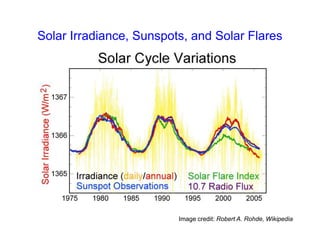

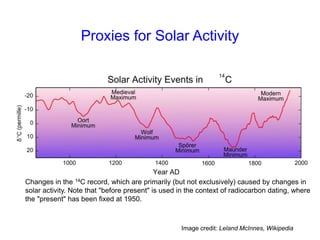

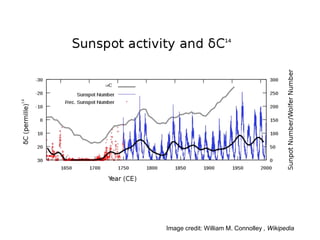

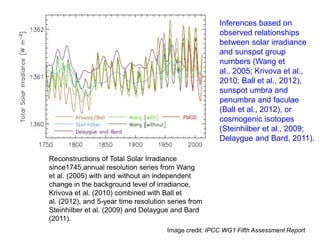

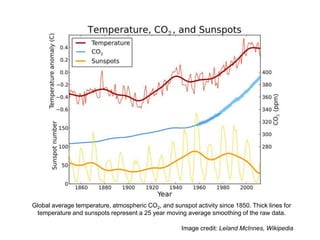

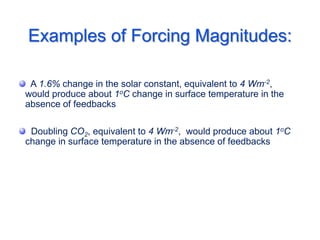

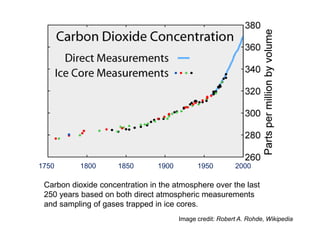

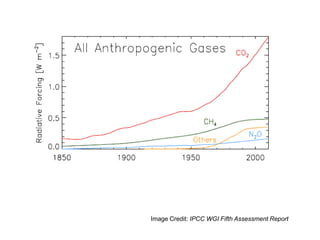

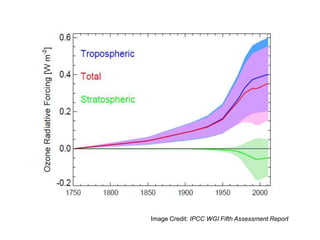

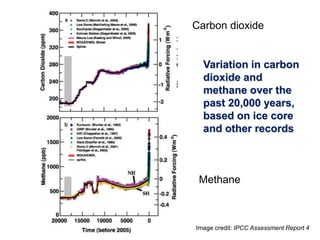

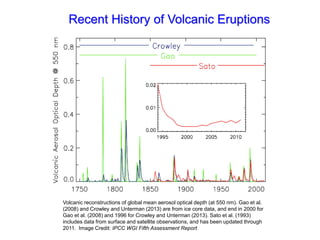

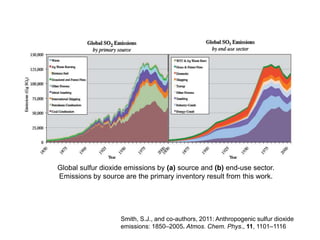

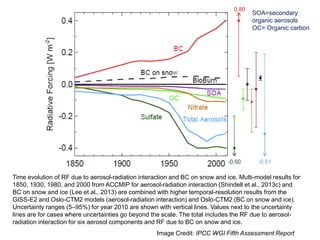

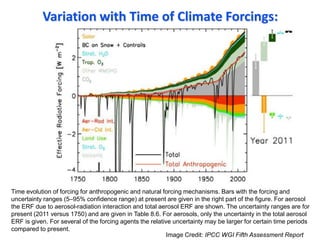

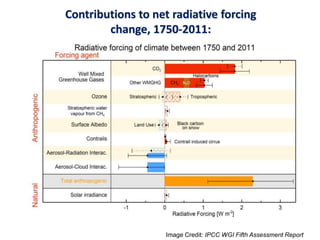

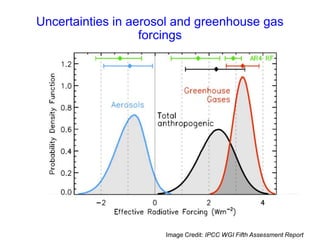

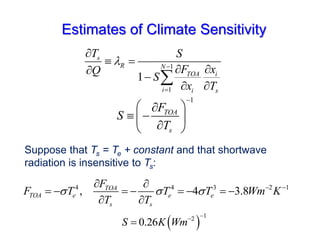

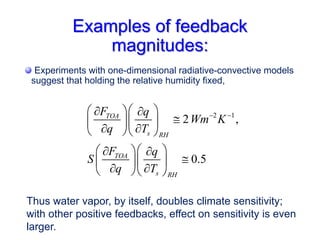

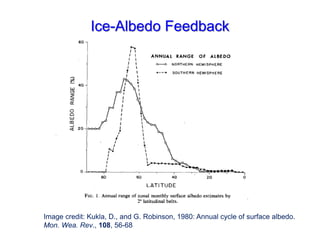

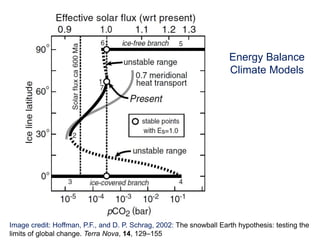

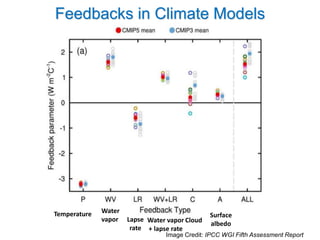

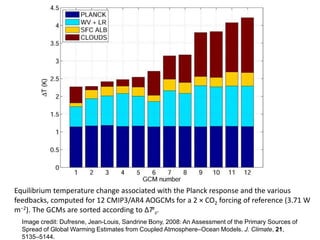

This document discusses climate forcings and feedbacks. It provides examples of climate forcings such as changes in greenhouse gases, solar irradiance, volcanic eruptions and aerosols. It also discusses examples of feedbacks like water vapor, ice-albedo, and clouds. The document shows how feedbacks amplify the initial response to forcing and increase climate sensitivity. It presents estimates of climate sensitivity from 1D models and comparisons of feedbacks simulated in climate models.