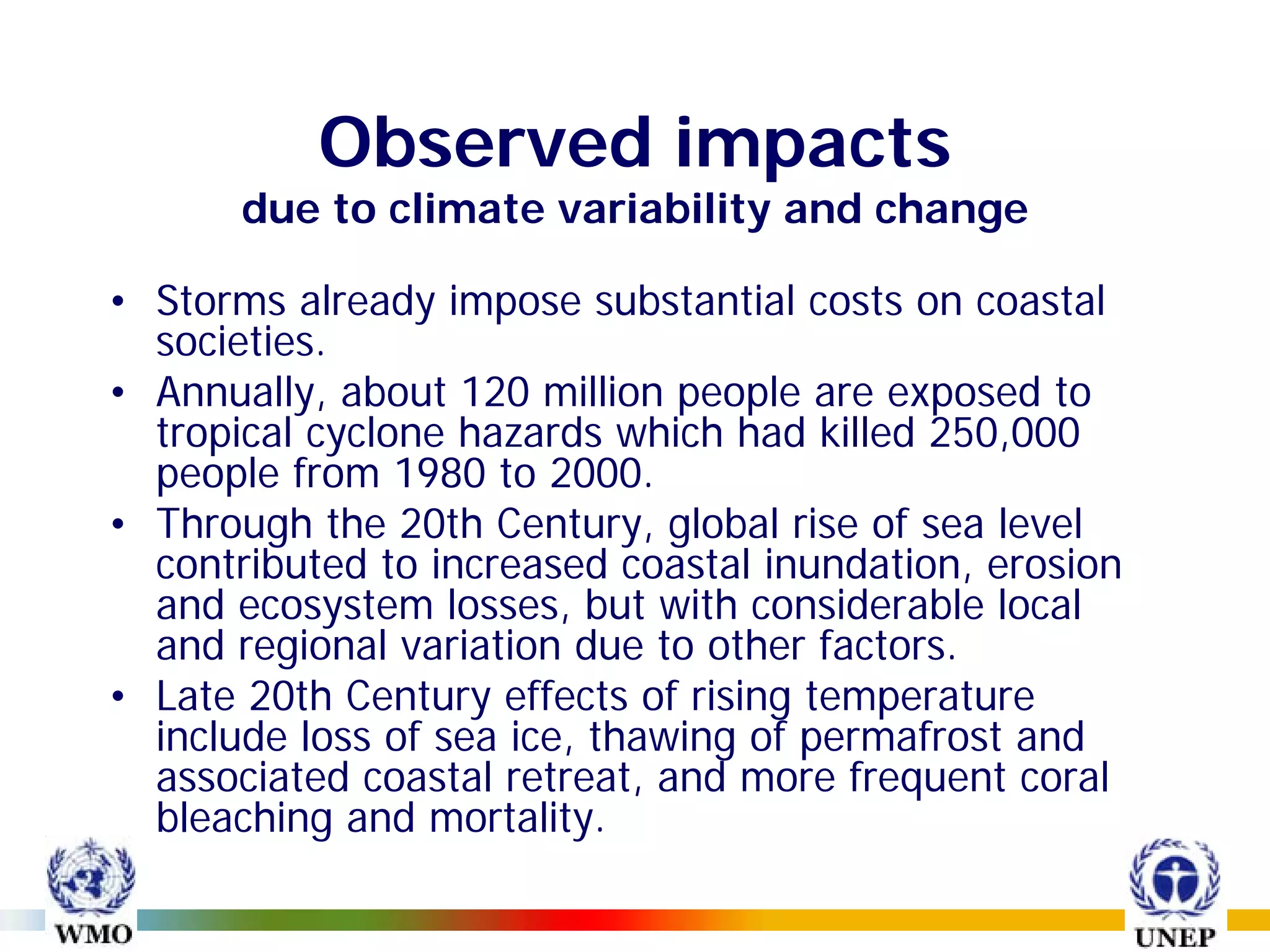

Coasts will face increasing risks from climate change through this century. Impacts include more frequent flooding, erosion, ecosystem loss, and damage from storms. These risks disproportionately threaten dense, low-lying coastal populations. While adaptation is challenging, a combination of protection, accommodation, and retreat strategies can reduce risks. However, sea level rise will continue for centuries, potentially questioning the viability of some coastal settlements without mitigation to limit long-term rise.

![Main conclusions

• Coasts are experiencing the adverse consequences of hazards

related to climate and sea level [*** D].

• Coasts will be exposed to increasing risks over coming decades

due to many compounding climate-change factors [*** D].

• The impact of climate change on coasts is exacerbated by

increasing human-induced pressures [*** C].

• Adaptation for the coasts of developing countries will be more

challenging than for coasts of developed countries, due to

constraints on adaptive capacity [** D].

• Adaptation costs for vulnerable coasts are much less than the

costs of inaction [** N].

• The unavoidability of sea-level rise even in the longer-term

frequently conflicts with present-day human development

patterns and trends [** N].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/climate-changesimpactoncoastalregions-100707192238-phpapp02/75/Climate-changes-impact-on-coastal-regions-3-2048.jpg)