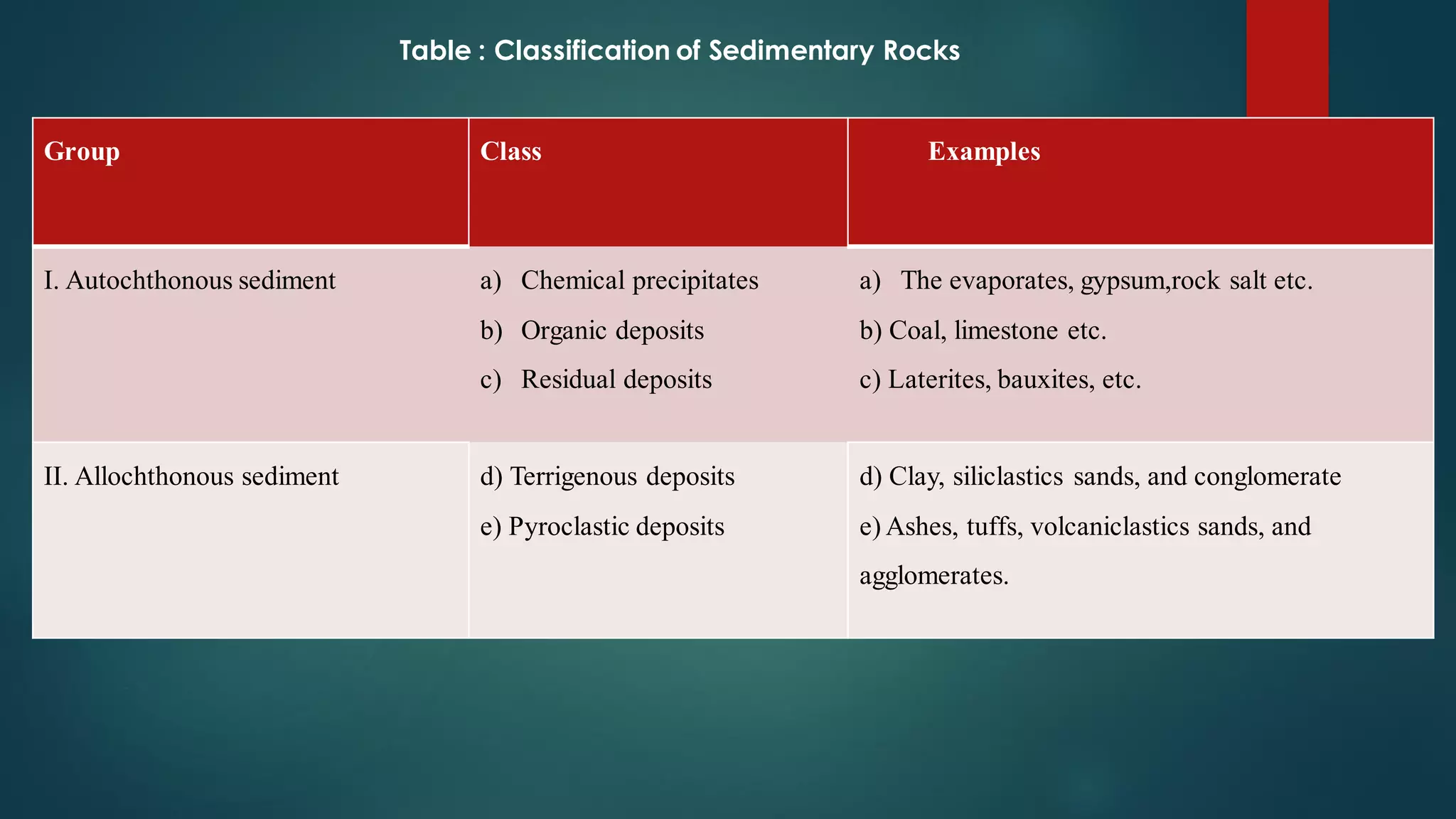

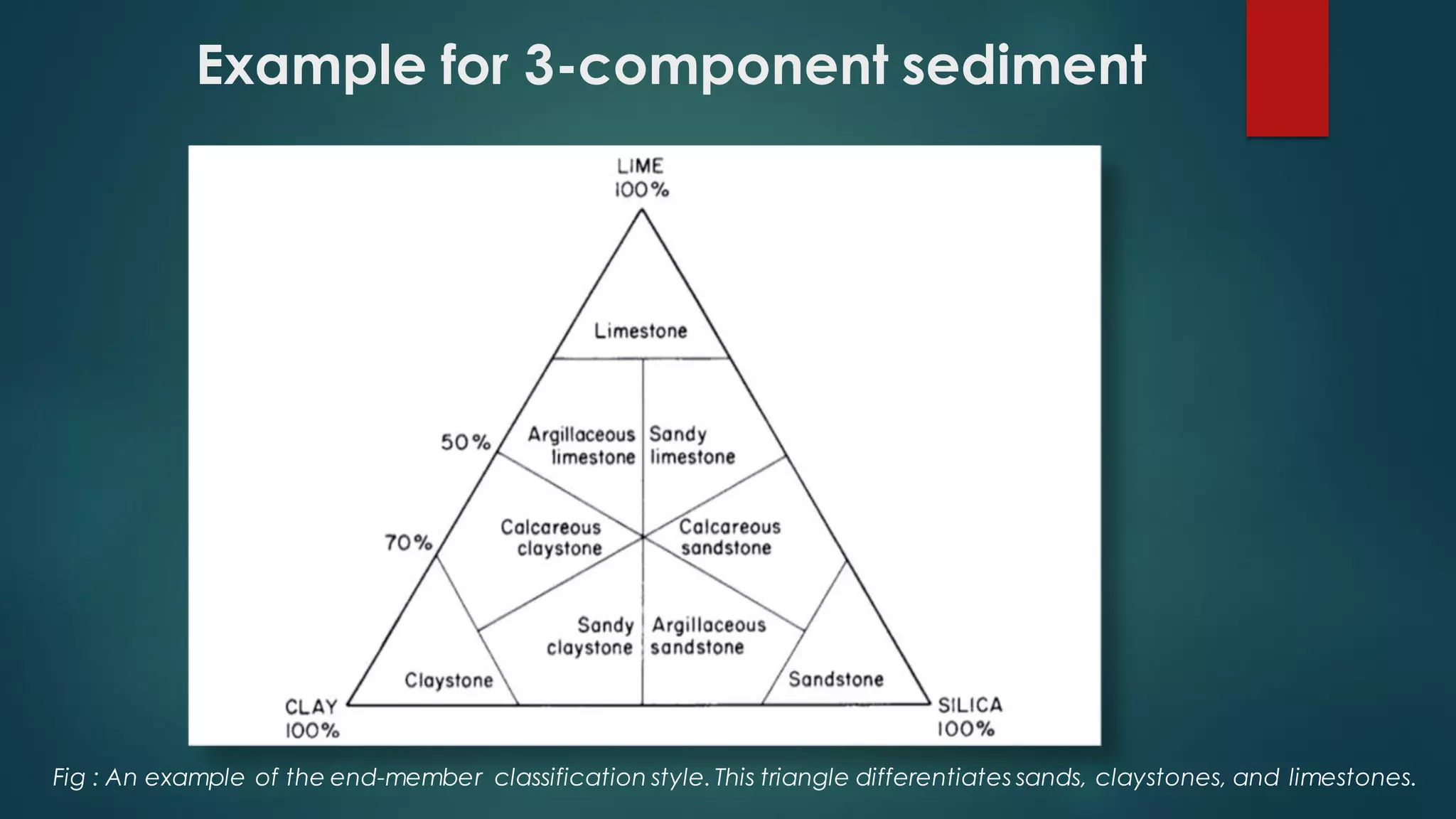

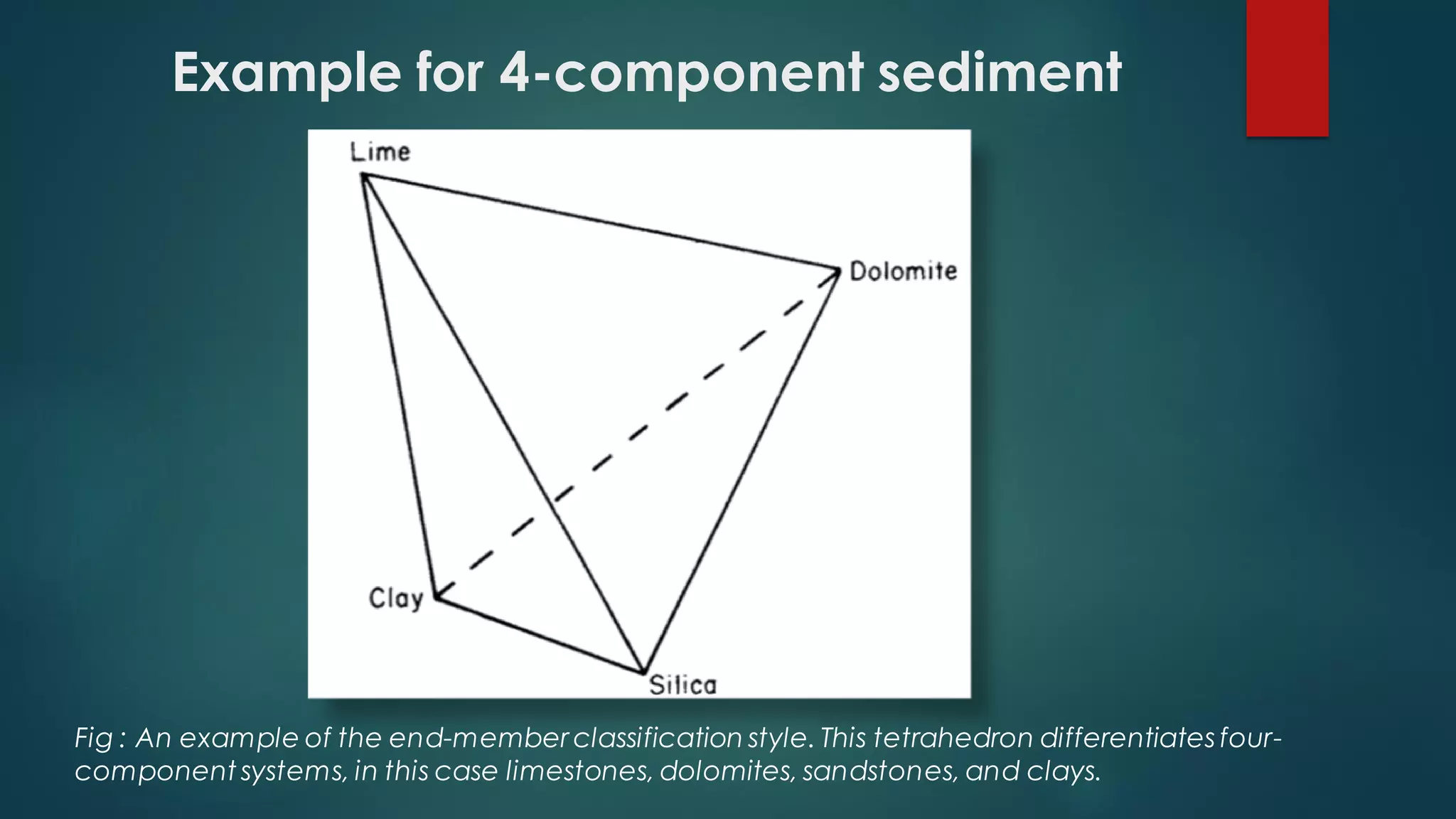

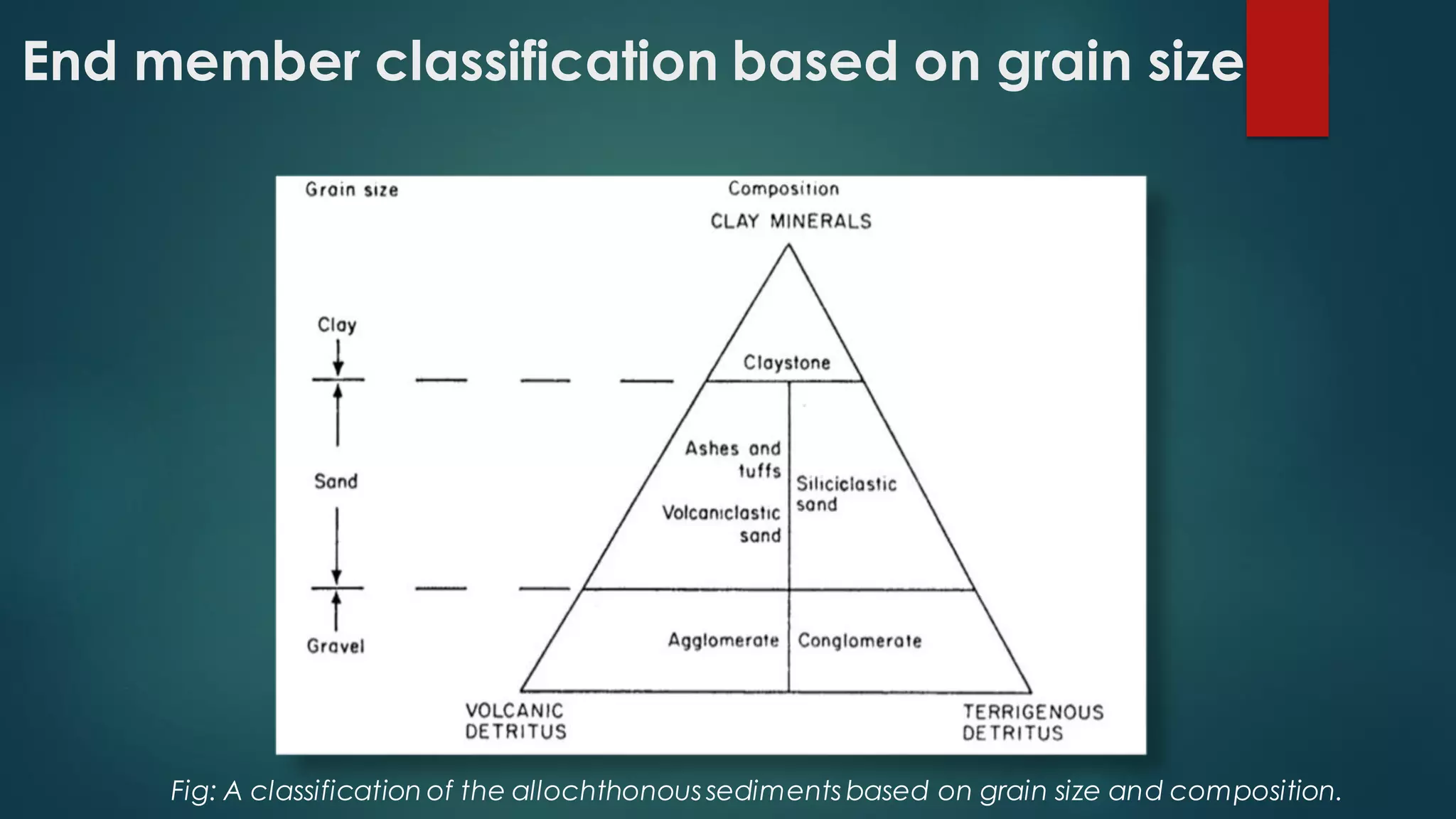

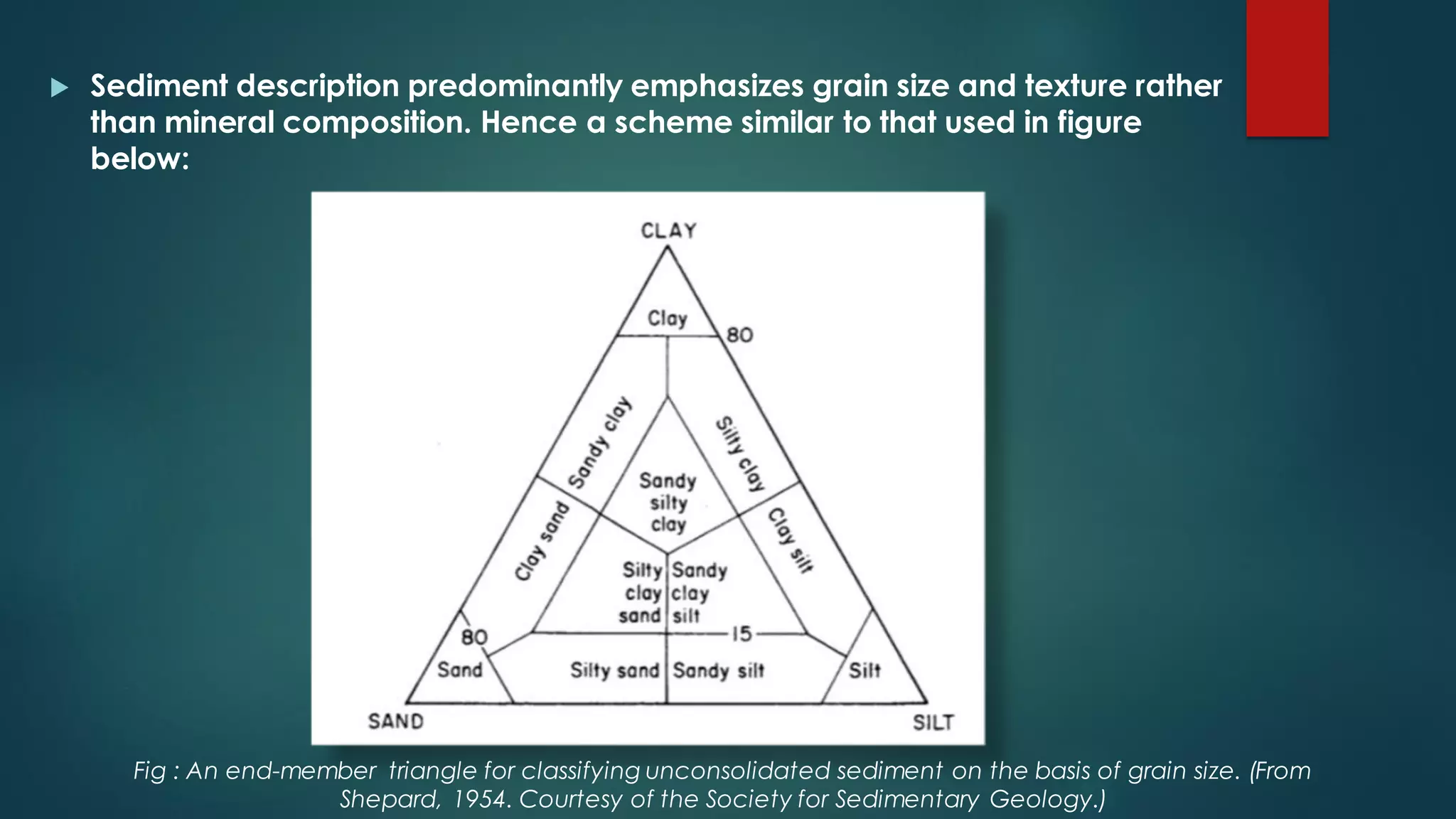

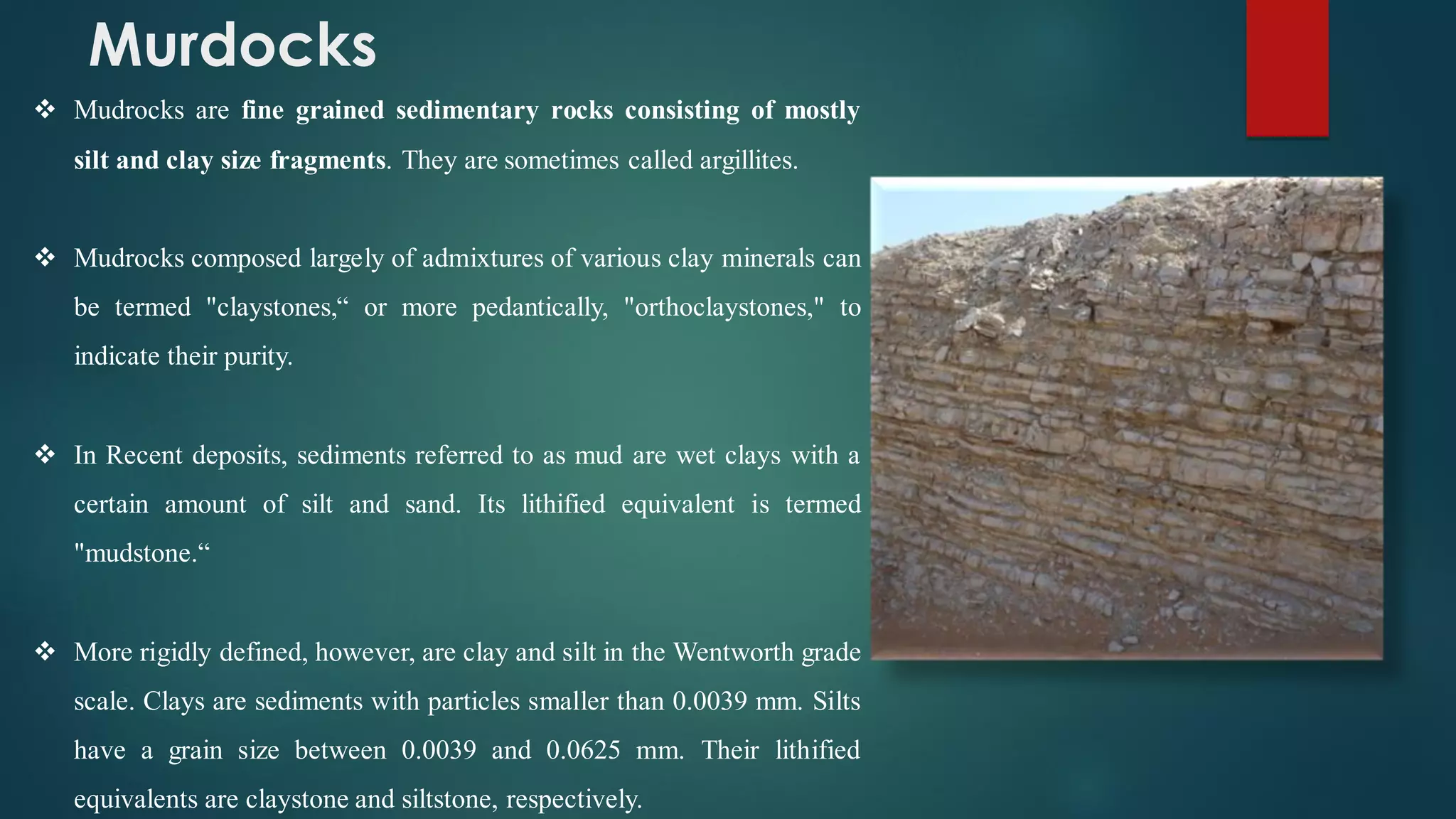

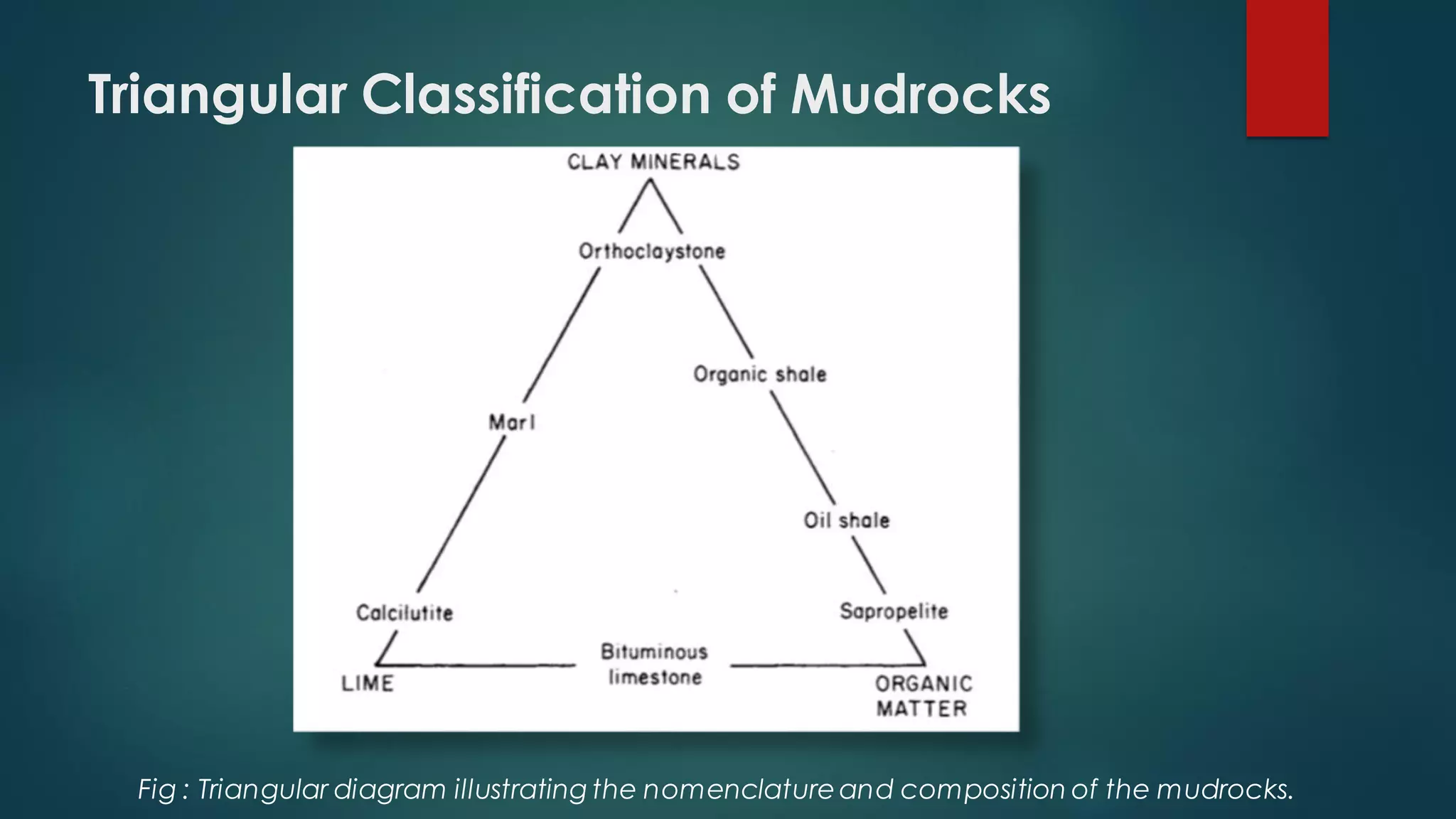

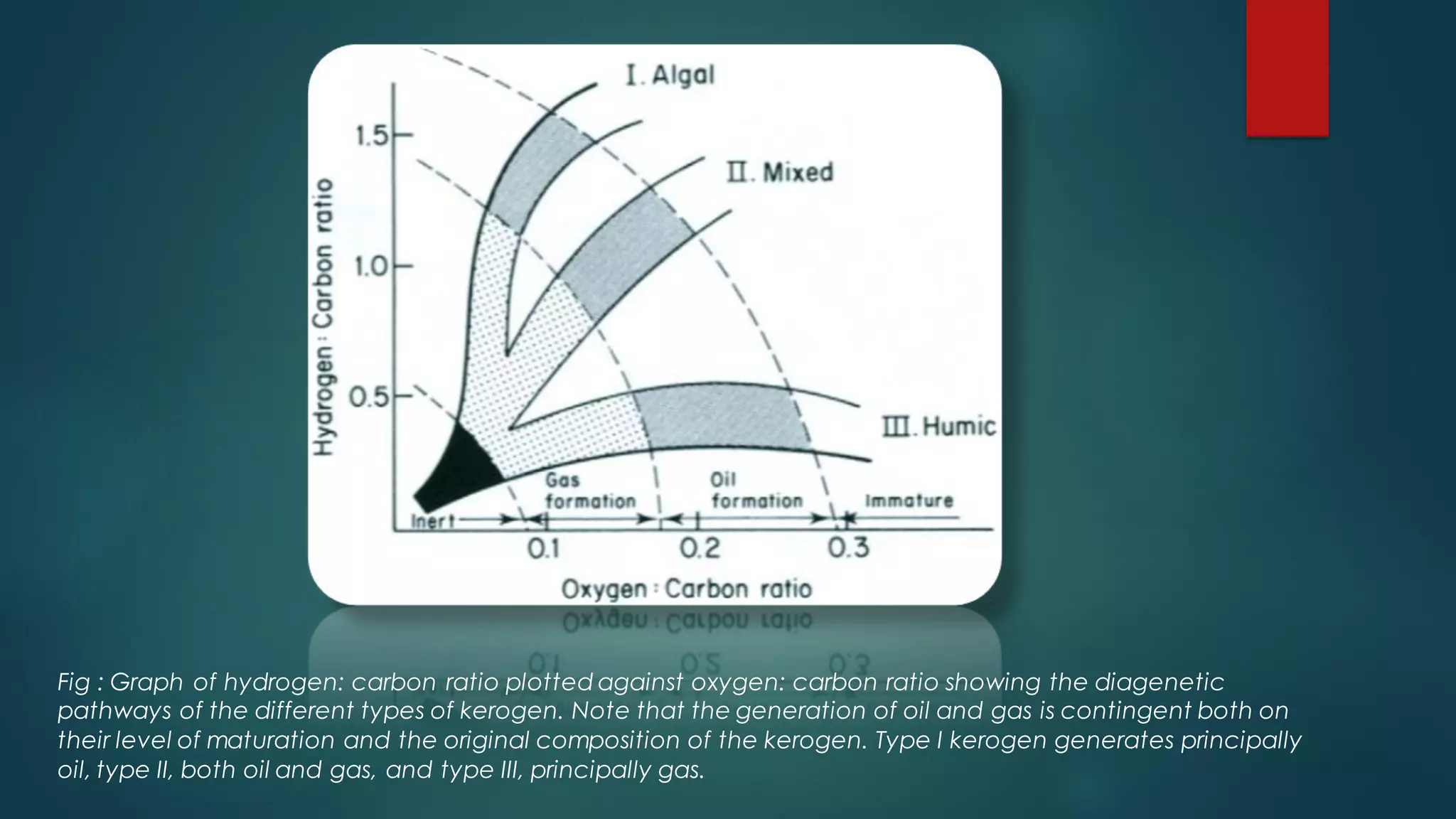

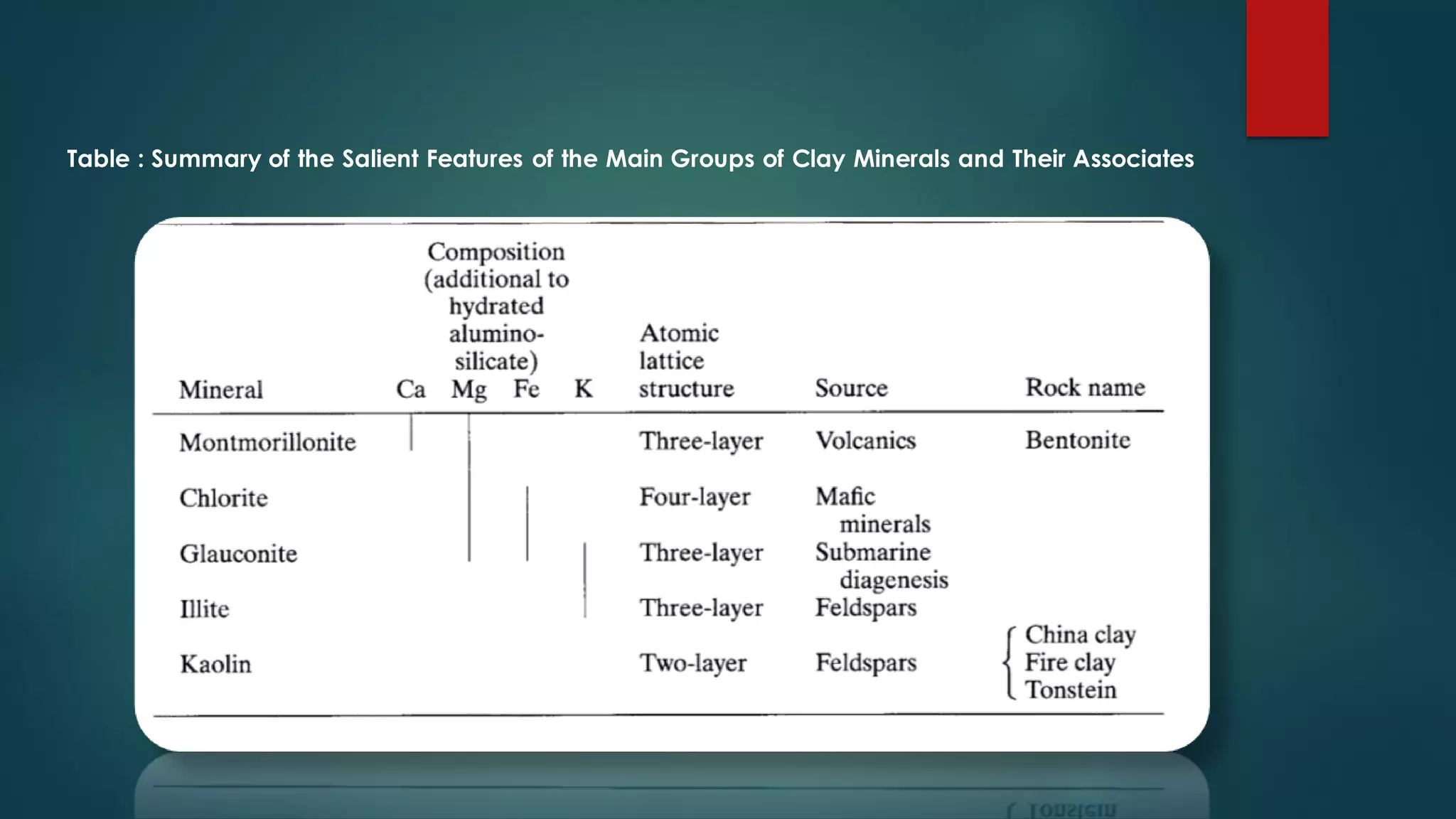

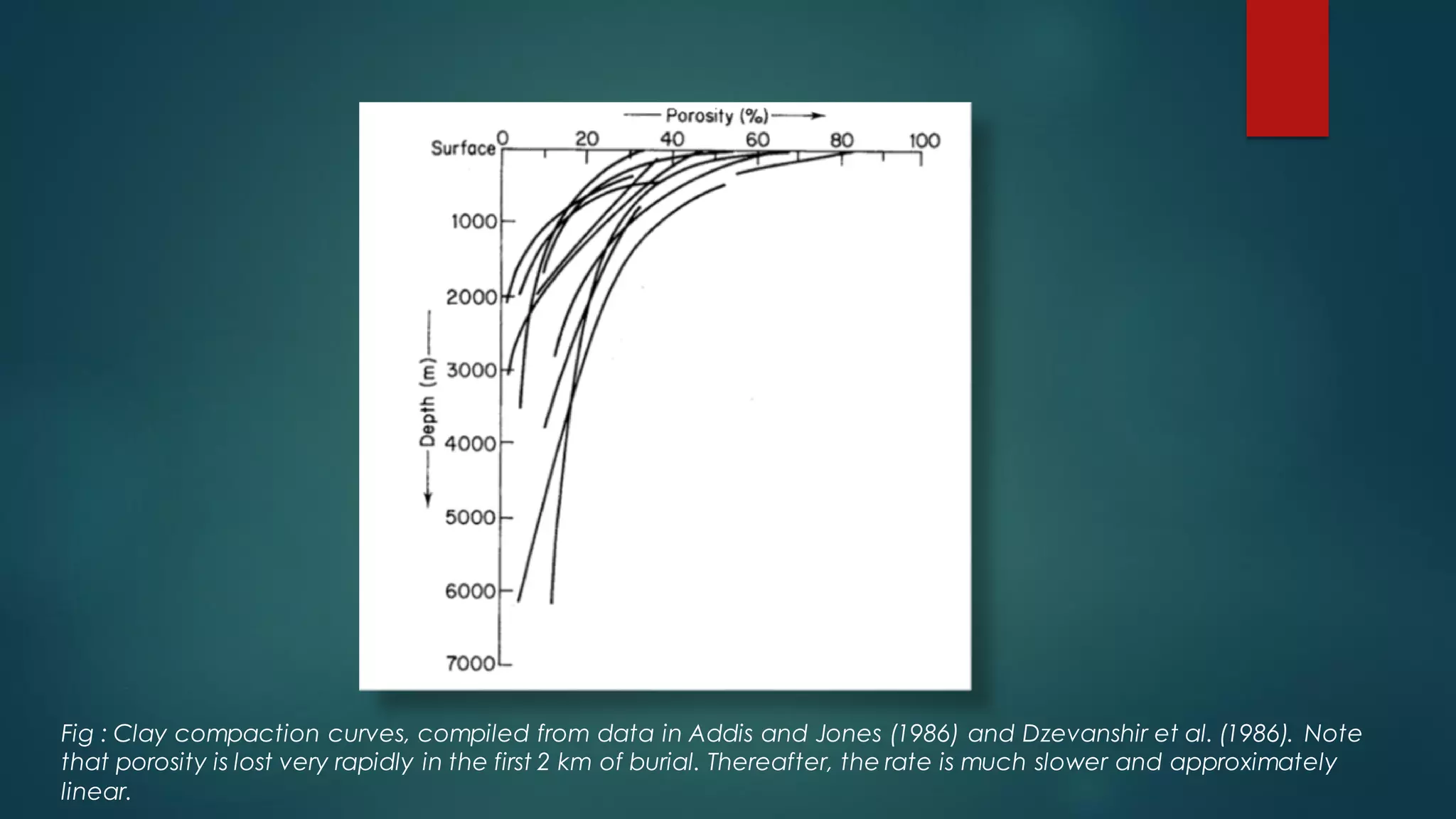

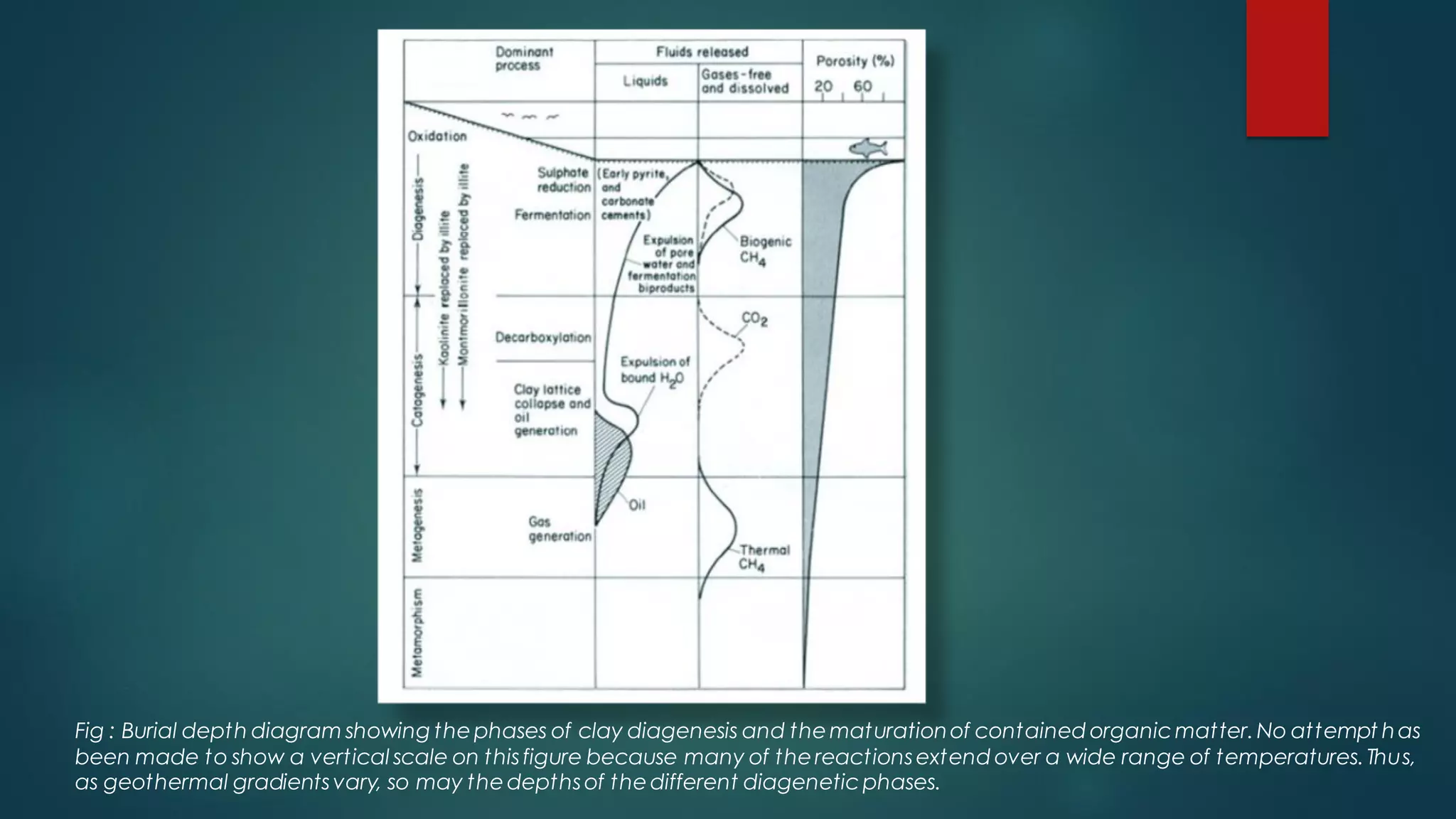

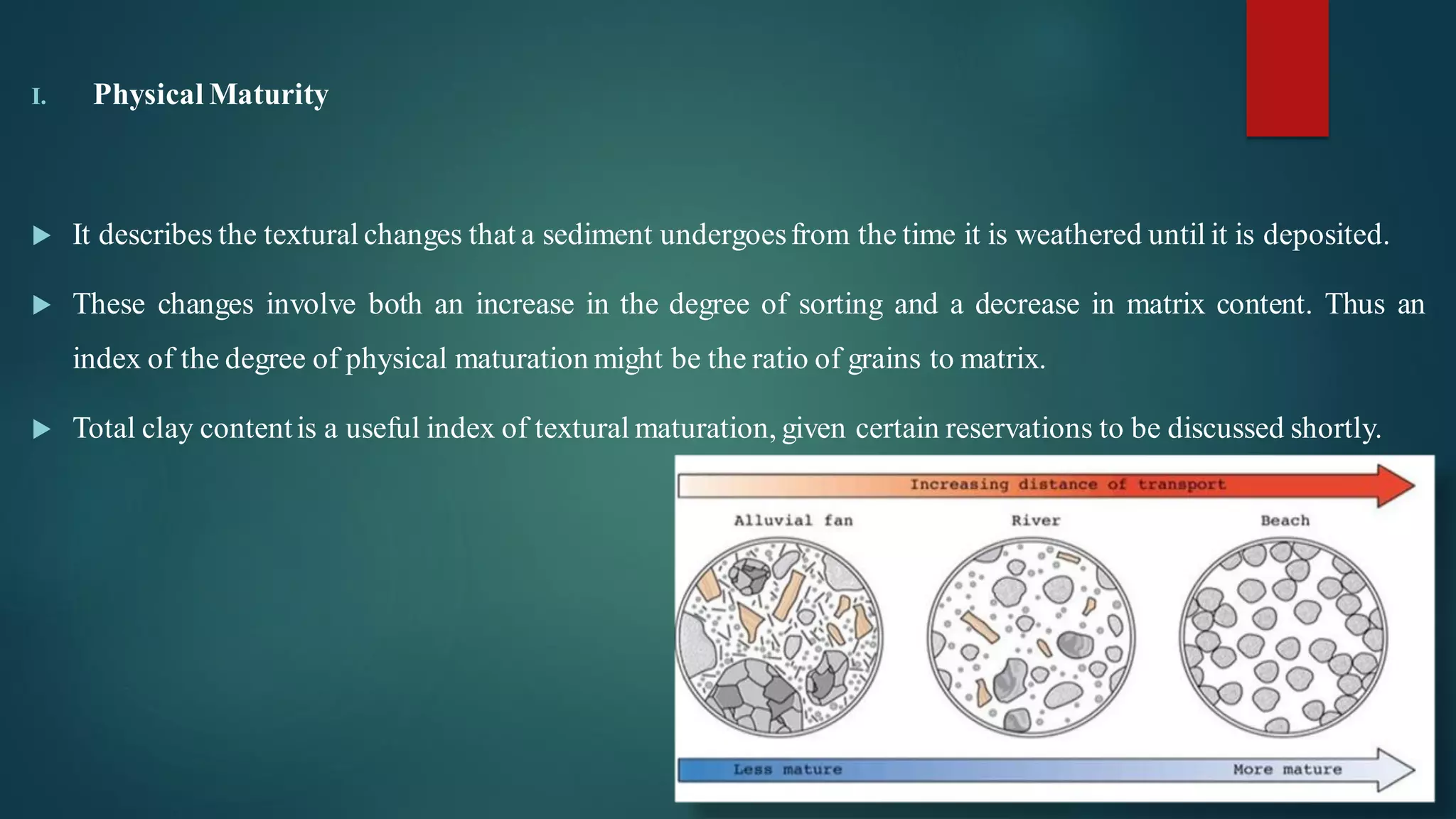

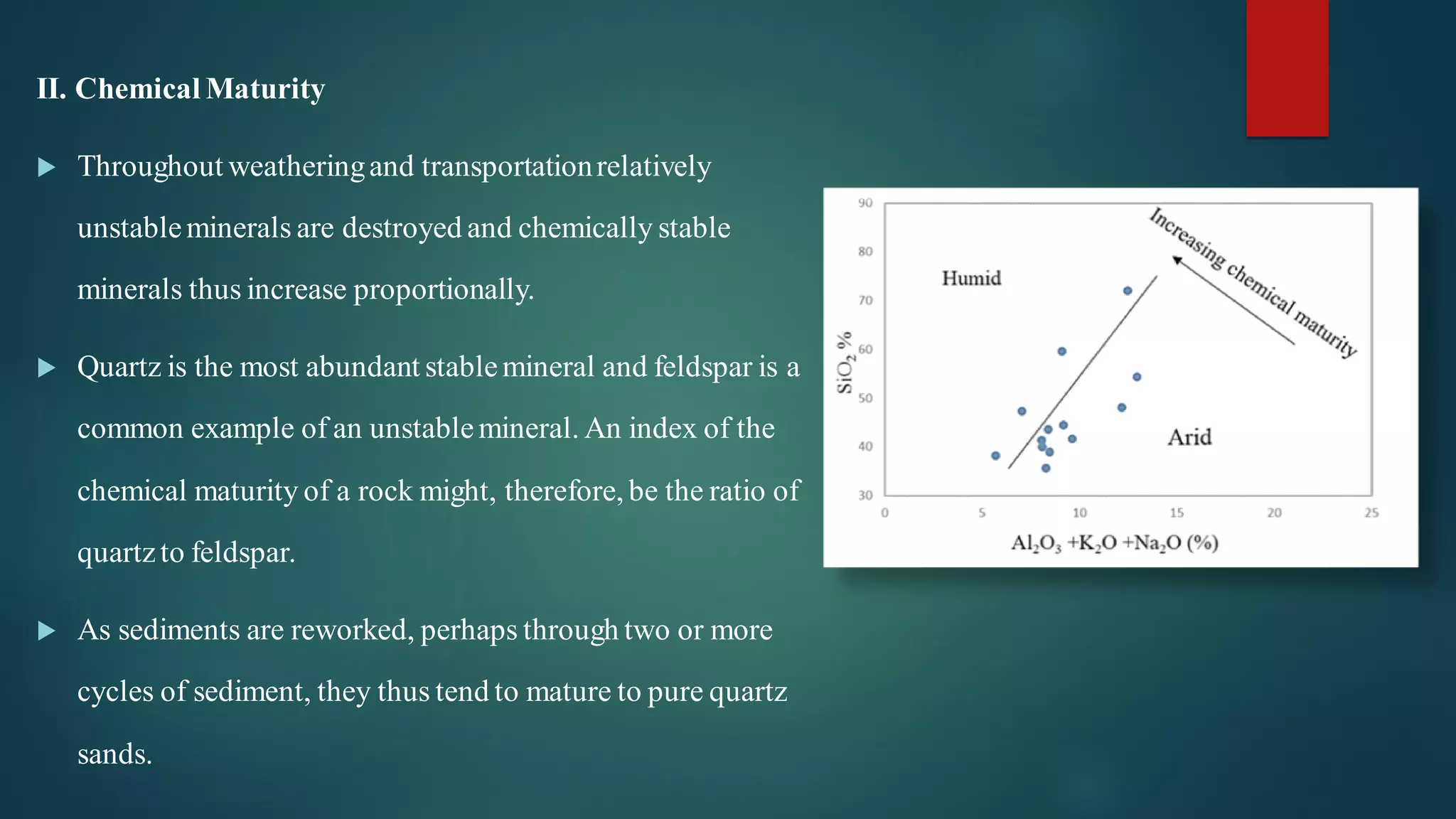

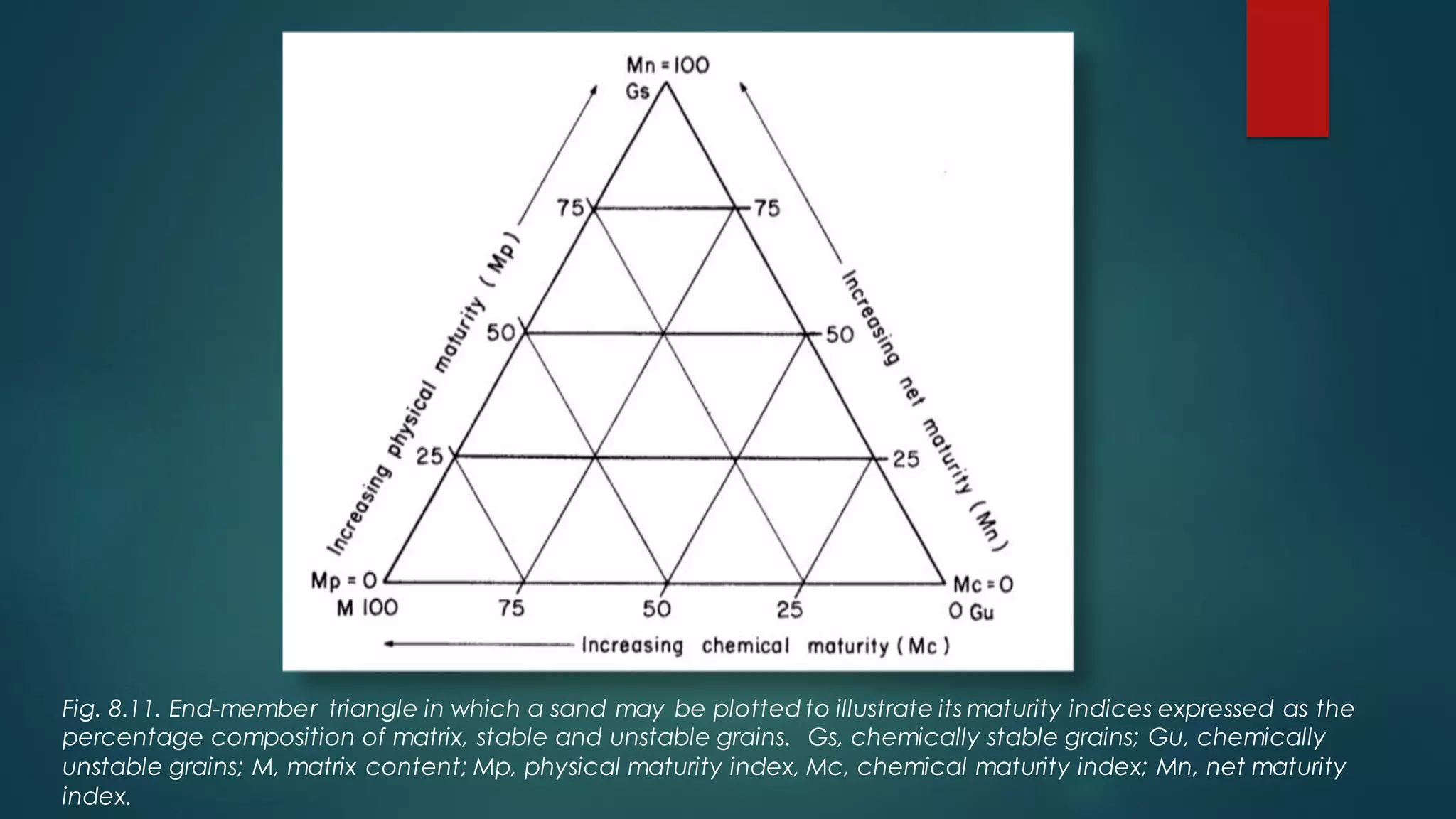

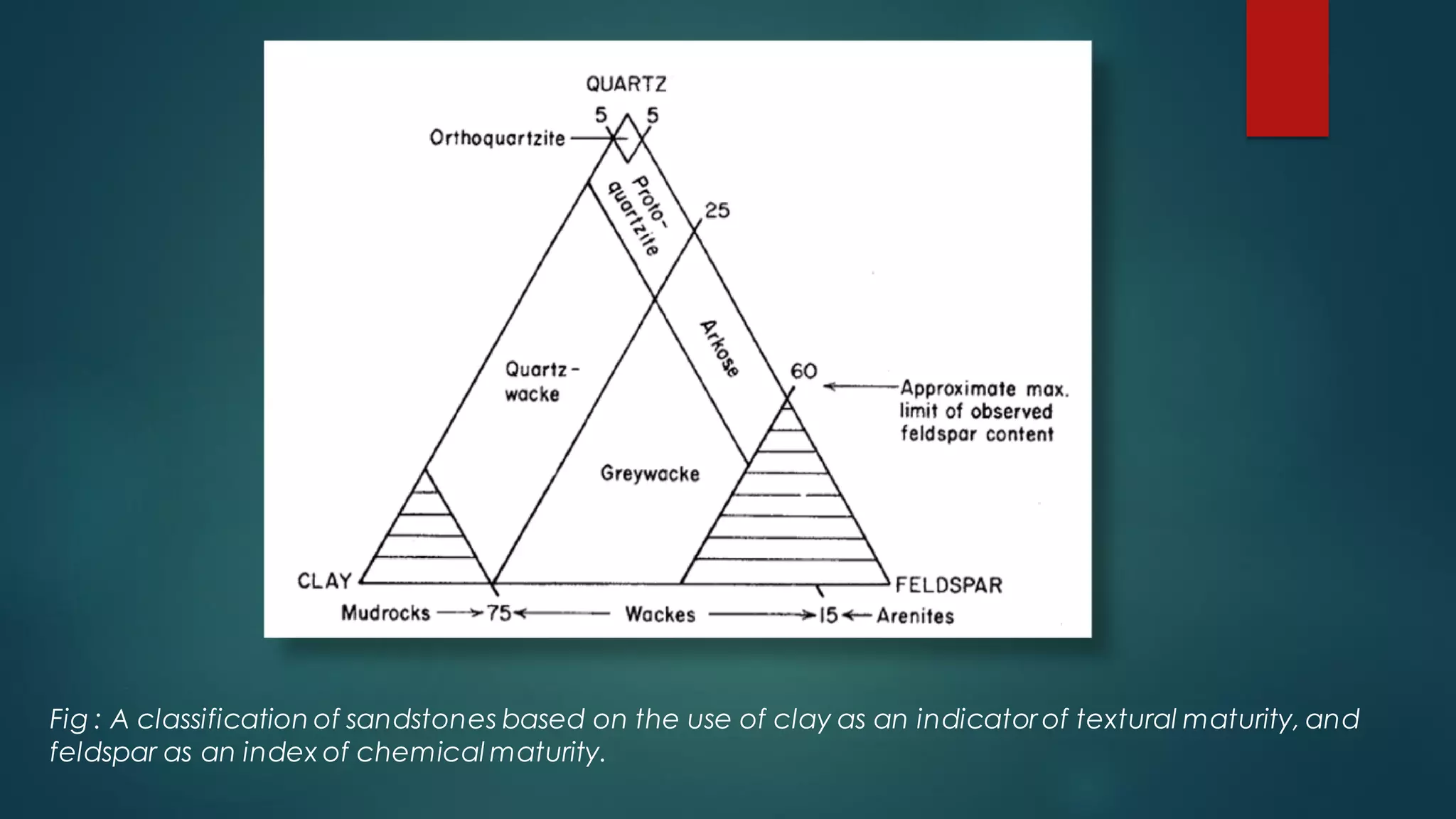

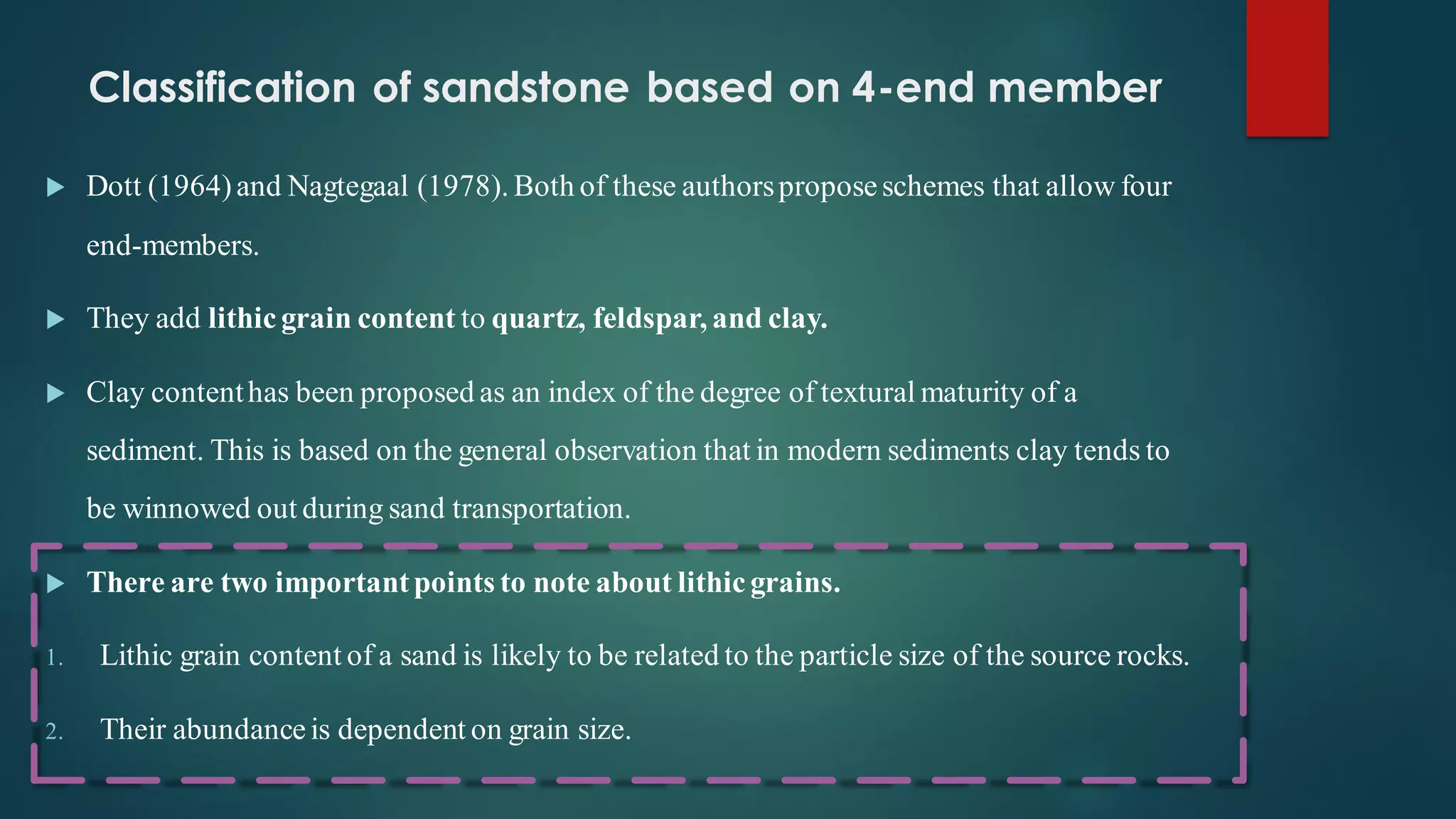

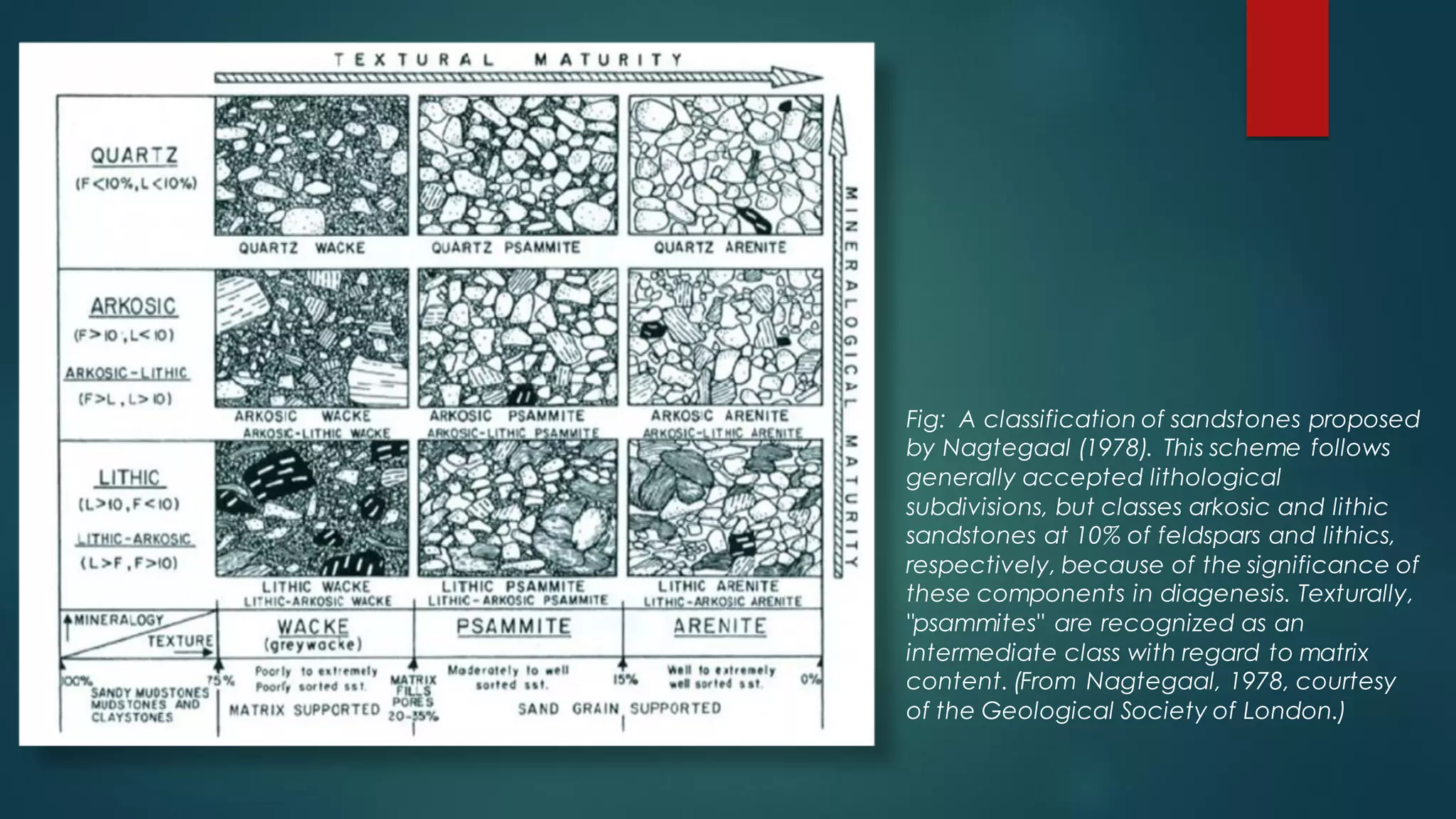

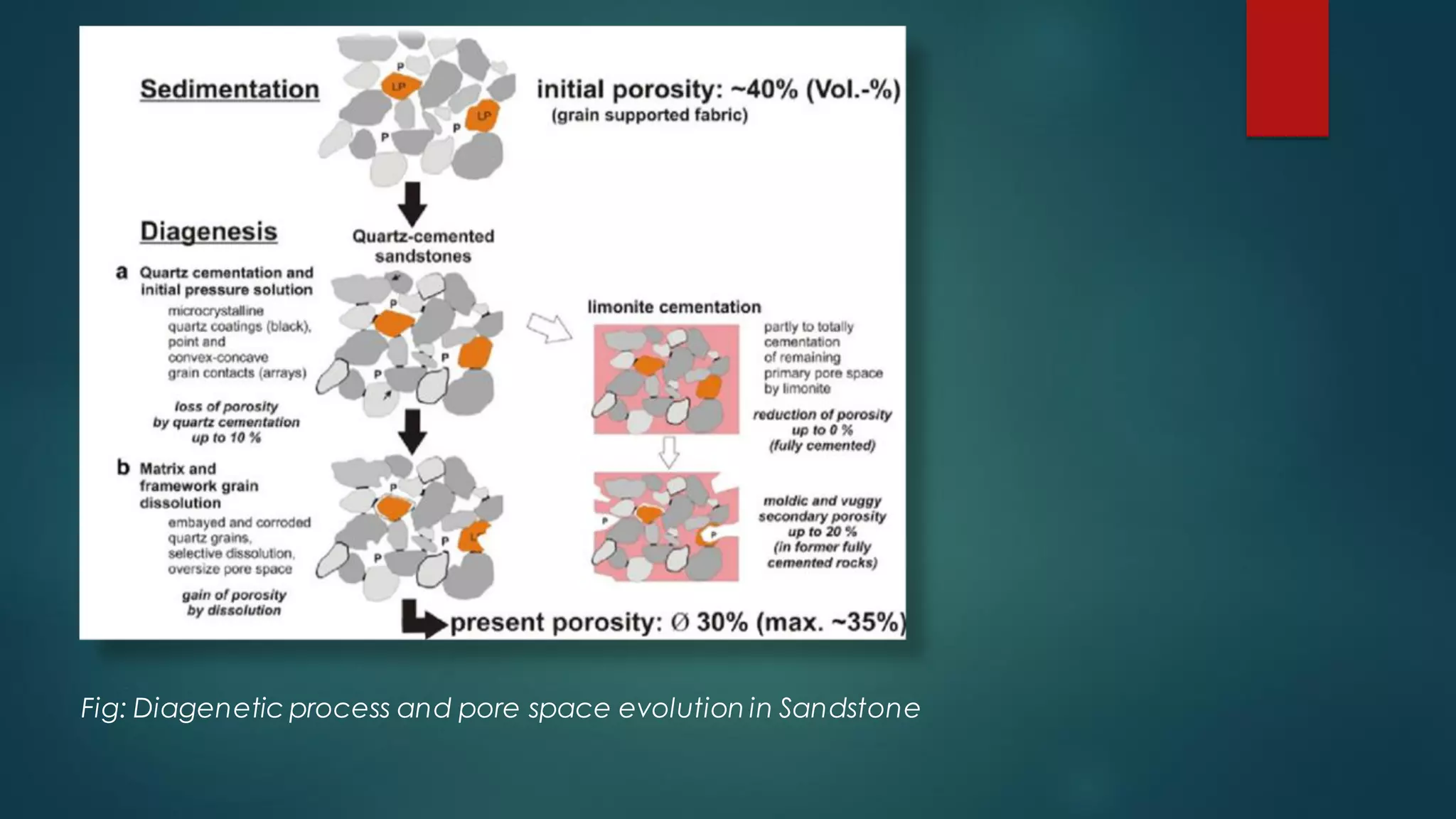

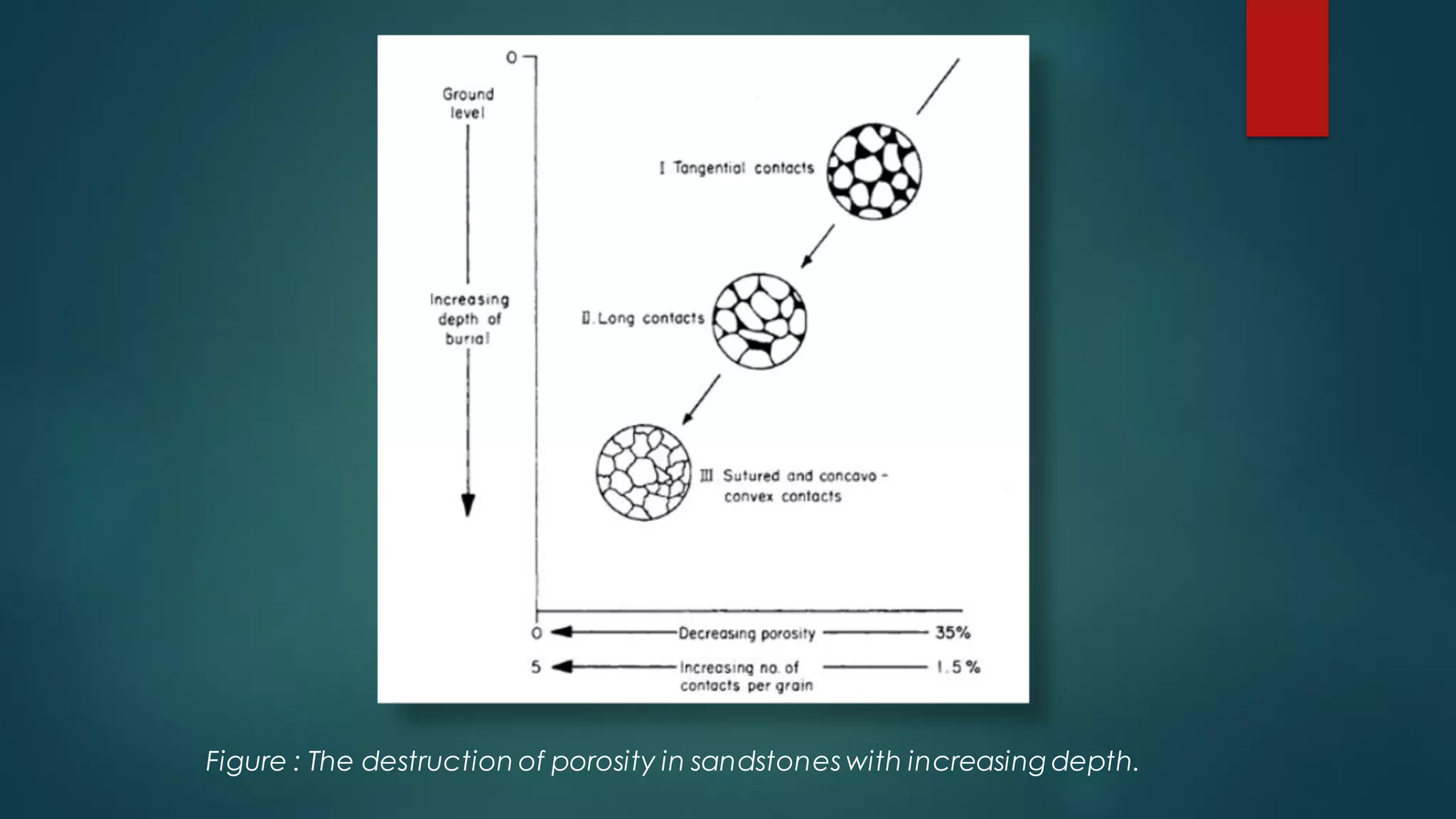

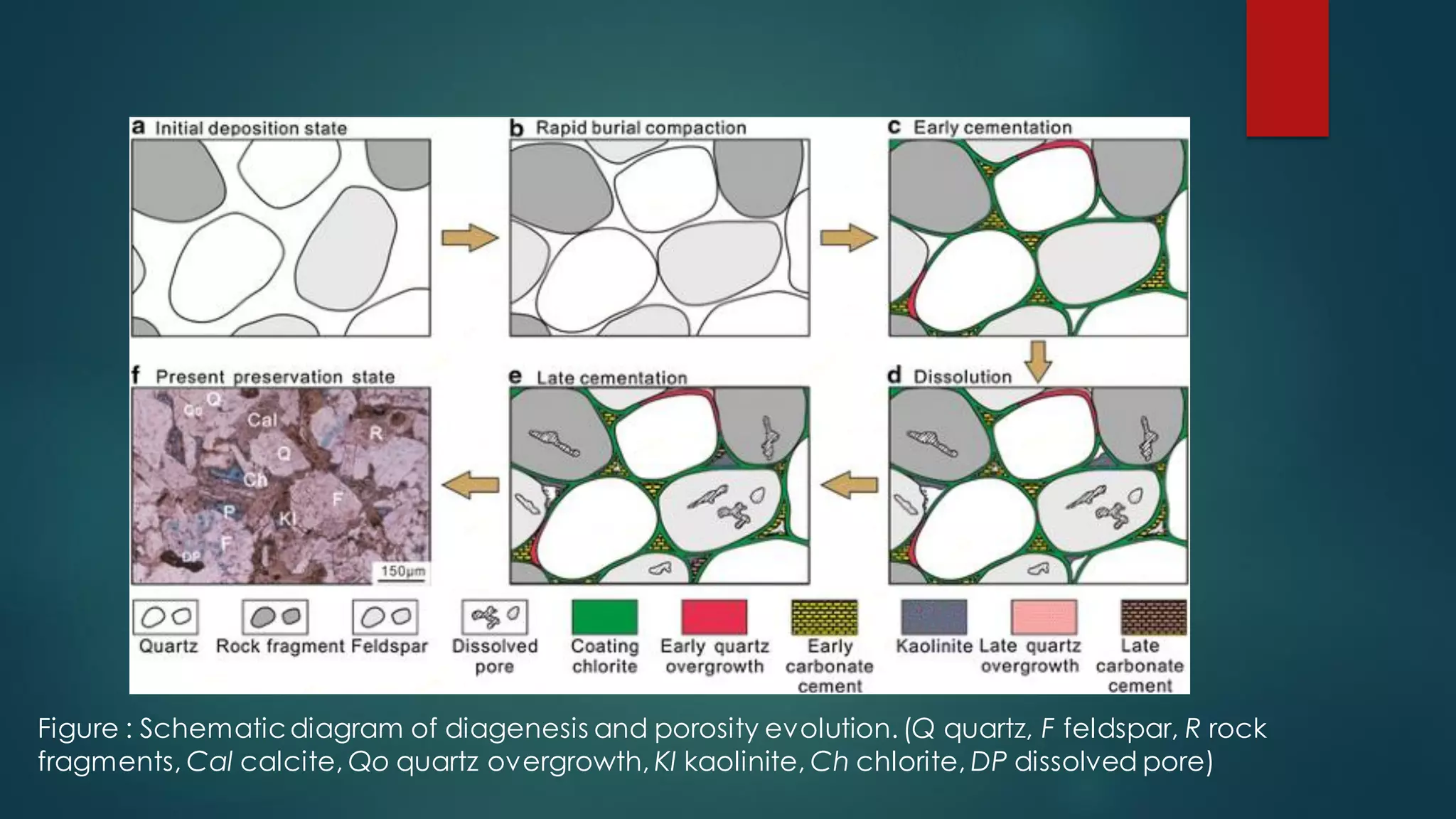

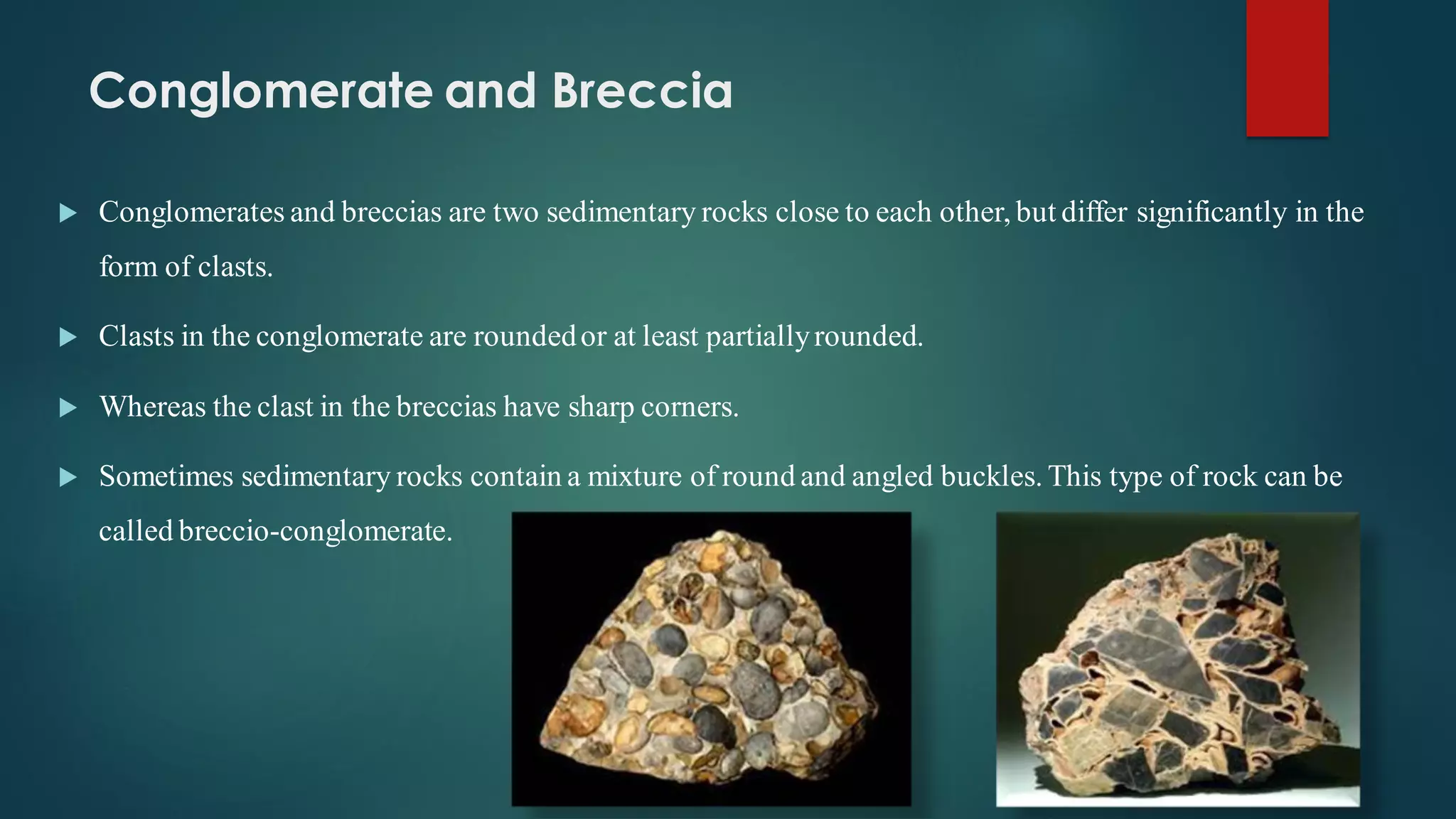

The document discusses the classification of sedimentary rocks. It defines allochthonous sediments as terrigenous and pyroclastic sediments that have been transported to the depositional environment, while autochthonous sediments form in situ. Allochthonous sediments can be classified based on grain size, mineral composition, and degree of maturity. Mudrocks and sandstones are discussed in more detail, including their composition, diagenetic changes over burial, and nomenclature based on textural and chemical maturity.