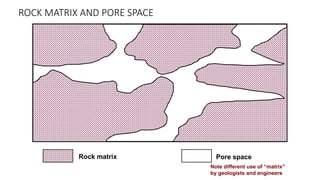

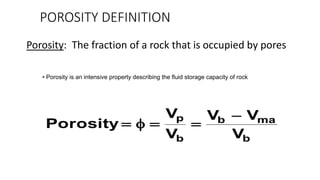

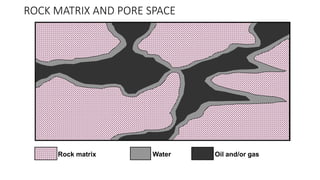

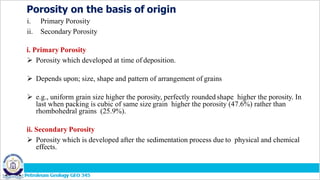

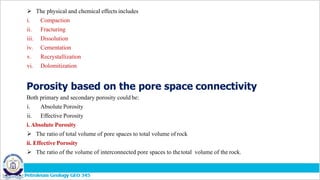

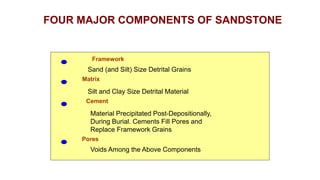

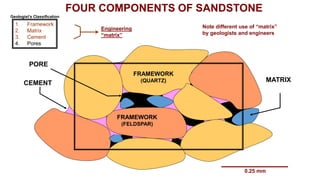

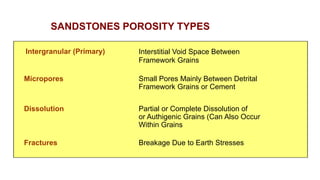

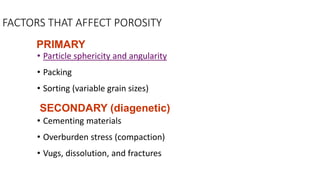

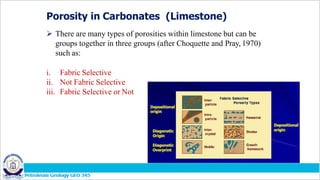

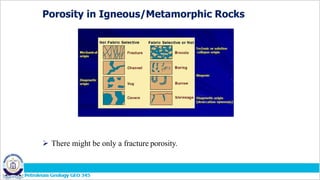

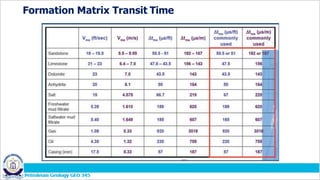

This document provides information on reservoir rocks and unconventional oil sources. It defines reservoir rocks as porous and permeable rocks that contain oil and gas. Reservoir rocks can be clastic rocks like sandstone, carbonate rocks like limestone, or rare igneous/metamorphic rocks. The key properties of reservoir rocks are porosity, which is the percentage of pore space, and permeability, which is the ability of fluids to flow through the rock. Unconventional oil sources discussed include oil shales, oil sands, coal liquification, and others.