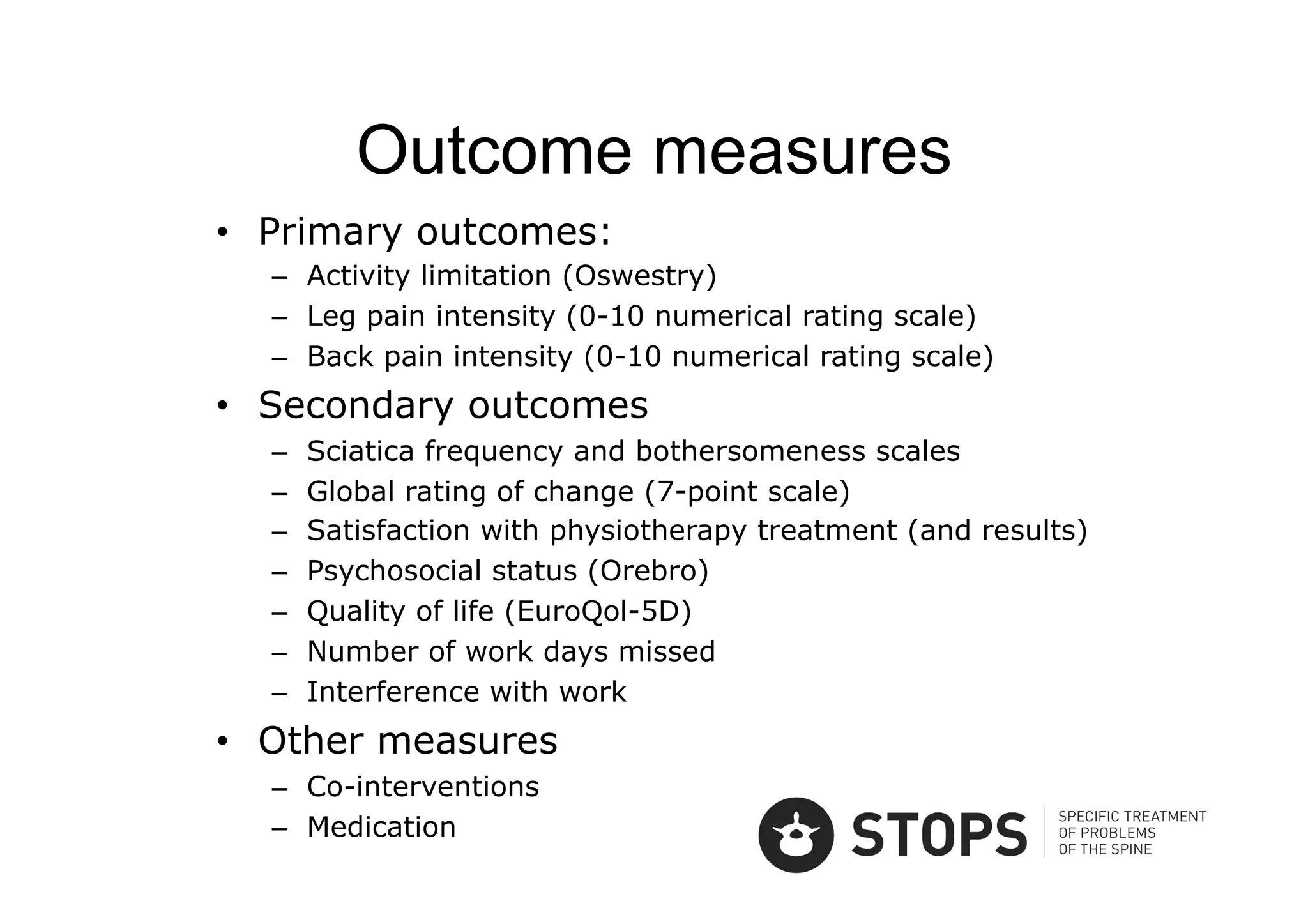

The document discusses the specific treatment and classification of low back pain (LBP), emphasizing the need for targeted interventions based on individual assessments. It highlights recent evidence and recommendations for managing conditions like disc herniation and radiculopathy, as well as generic approaches for acute and chronic LBP. The findings indicate that while there are effective strategies, many conventional treatments may show minimal clinical significance compared to usual care.