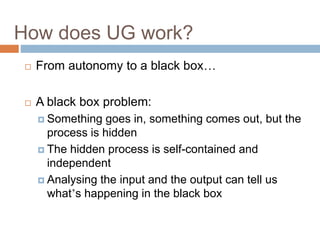

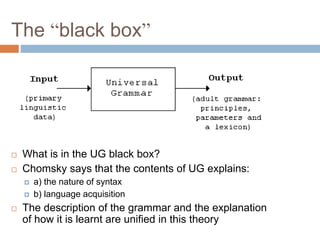

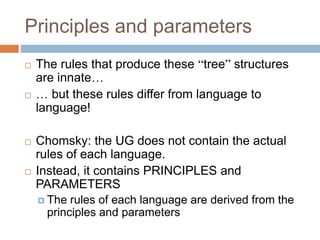

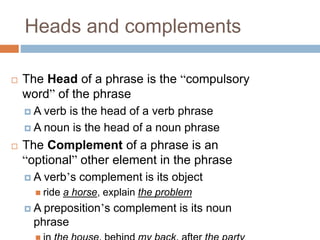

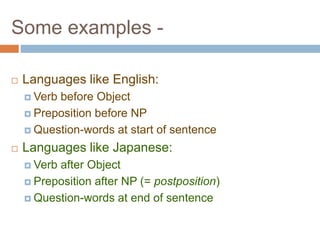

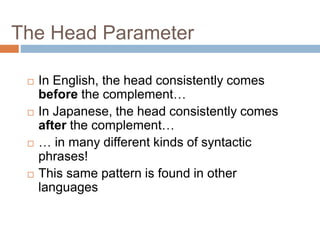

Chomsky's theory of Universal Grammar (UG) proposes that language acquisition is made possible by innate, language-specific knowledge that all human beings share. According to the theory, UG contains principles of grammar and parameters that children use to set the rules of their native language by analyzing linguistic input. The principles are universal aspects of syntax, while the parameters allow for variation between languages and are set based on evidence in a child's environment. Chomsky argues that UG acts as an autonomous "black box" that generates grammatical sentences through rules determined by parameter settings.

![2

The paradox of language acquisition

[A]n entire community of highly trained professionals,

bringing to bear years of conscious attention and

sharing of information, has been unable to duplicate

the feat that every normal child accomplishes by the

age of ten or so, unconsciously and unaided.

(Jackendoff 1994: 26)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chomskyanlinguistics2-101128130012-phpapp01/85/Chomskyan-linguistics-2-2-320.jpg)

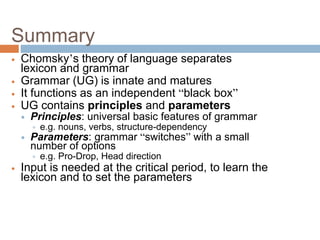

![The Pro-drop Parameter

Controls whether subject pronouns can be

dropped in the language

I understand Chomsky’s theory

* understand Chomsky’s theory WRONG

Spanish: [+ Pro-drop]

English and French: [- Pro-drop]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chomskyanlinguistics2-101128130012-phpapp01/85/Chomskyan-linguistics-2-24-320.jpg)

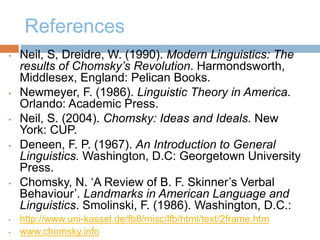

![The problems with

parameters

Some languages don’t fit into neat categories

e.g. German : partly Head First and partly Head

Last ???

It is hard to find good examples of parameter

setting in child data

Not much evidence for a sudden effect on

children’s speech from a parameter being set

e.g. young English-speaking children frequently

drop subjects (in a [- Pro-drop] language!) …

… and this falls off gradually not suddenly

What ARE these parameters anyway?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chomskyanlinguistics2-101128130012-phpapp01/85/Chomskyan-linguistics-2-31-320.jpg)

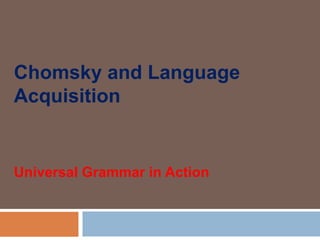

![Ignoring the data?

“An I-language approach [i.e. a Chomskyan

approach …] sees language acquisition as a

logical problem that can be solved in principle

without looking at the development of actual

children in detail.”

Cook and Newson (1996: 78)

Is this valid?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chomskyanlinguistics2-101128130012-phpapp01/85/Chomskyan-linguistics-2-33-320.jpg)