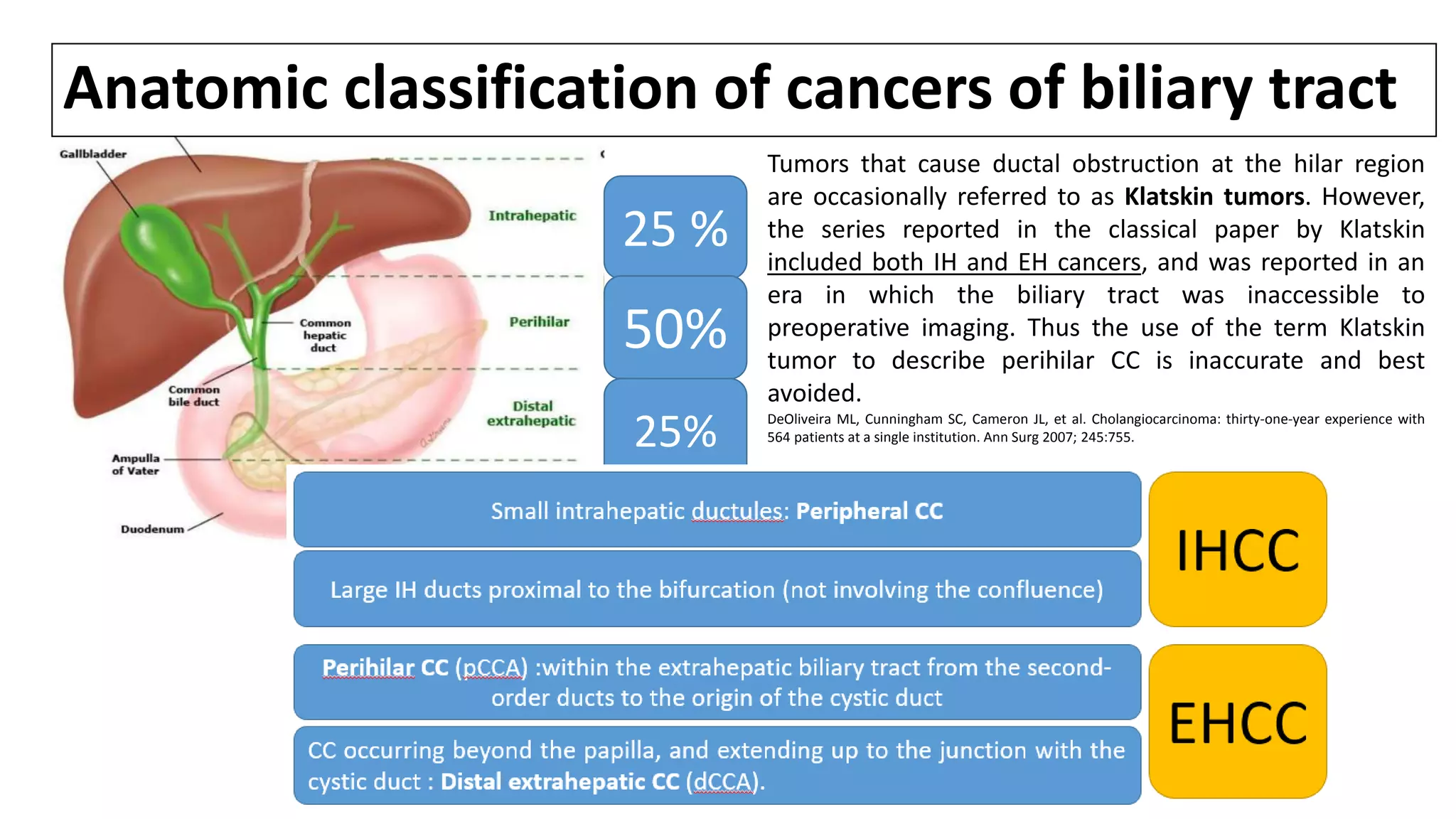

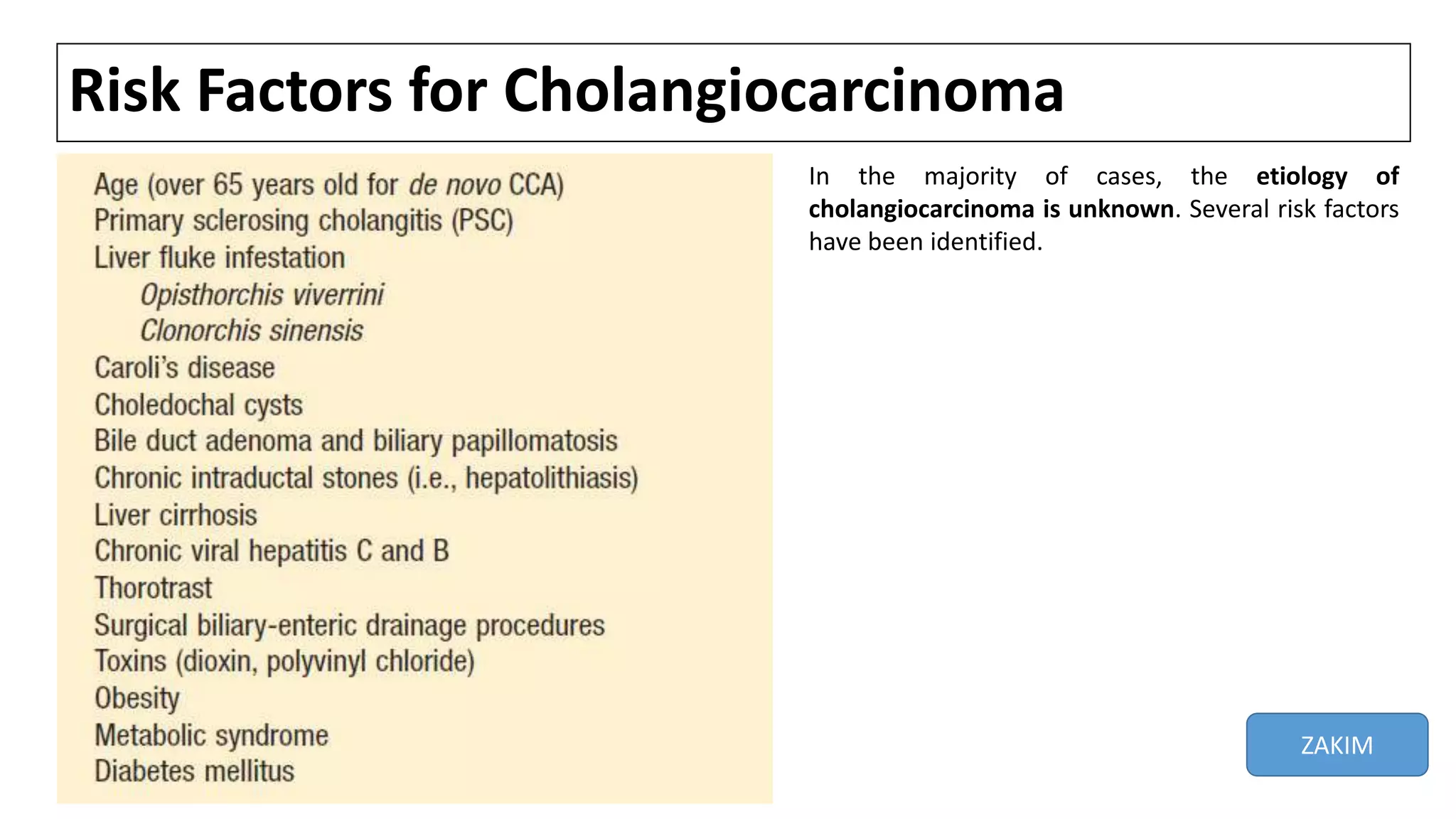

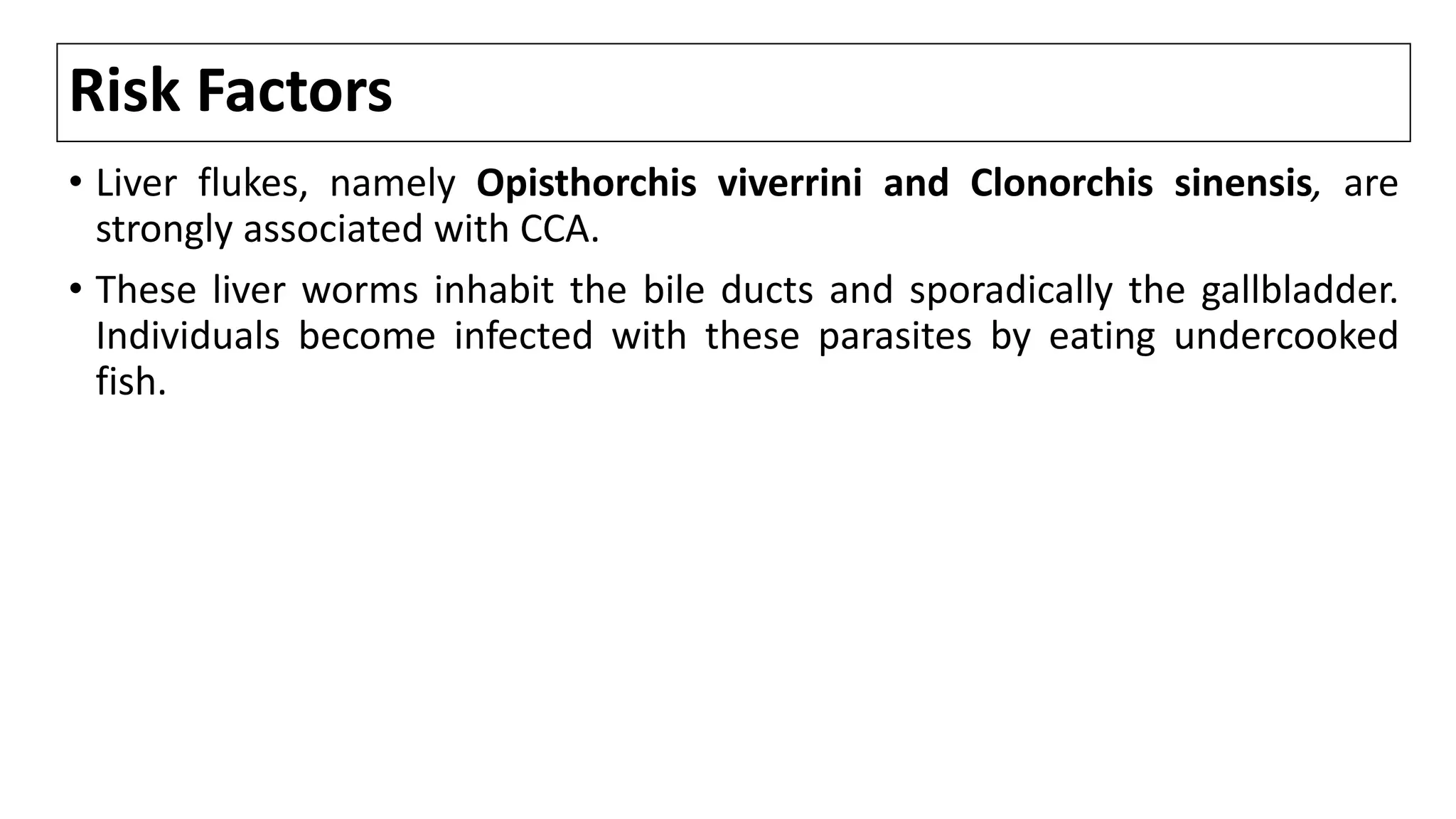

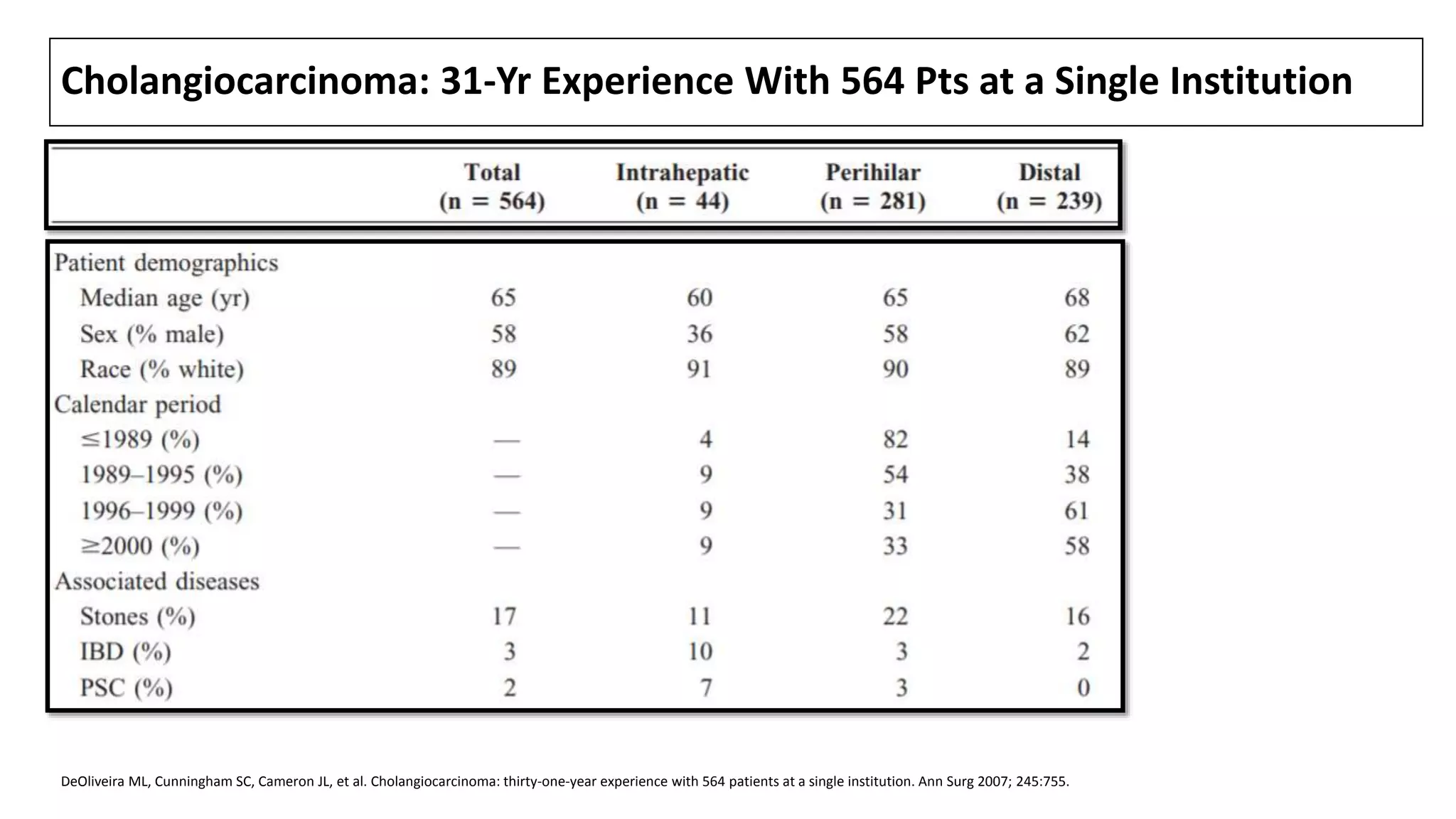

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a malignant tumor originating from the epithelial cells of the bile ducts and accounts for 10-20% of hepatobiliary neoplasms. The document discusses its anatomy, epidemiology, risk factors, and management, emphasizing the importance of screening in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) and the rising incidence of intrahepatic CCA. Risk factors include liver fluke infections, congenital abnormalities, and exposure to certain toxins, with a notable connection between PSC and the development of CCA.

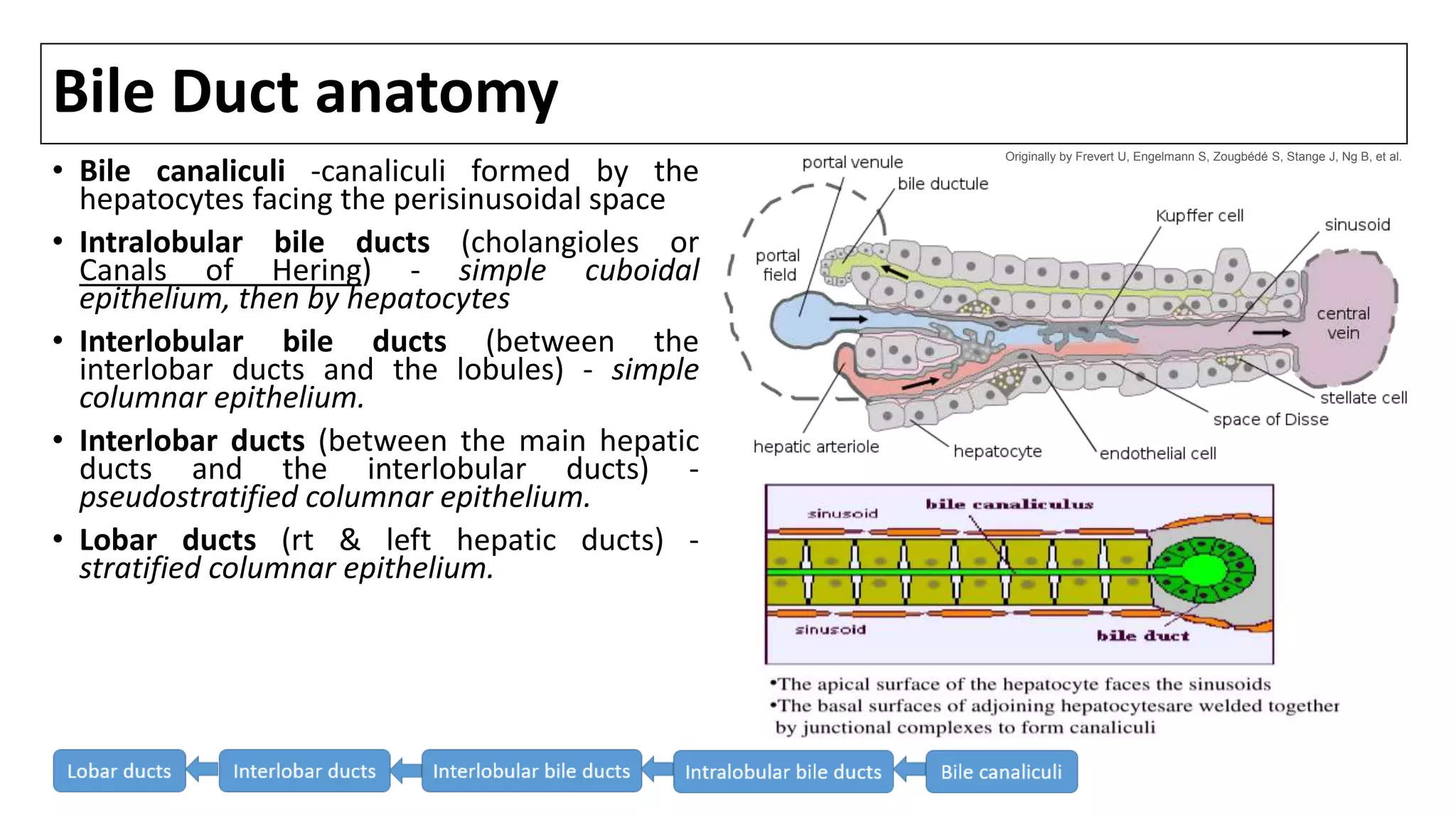

![Intrahepatic bile ducts

Bile canaliculi unite to form segmental bile ducts which

drain each liver segment. The segmental ducts then

combine to form sectional ducts with the following

pattern [1]:

•segments VI and VII: right posterior duct (RPD), coursing

more horizontally

•segments V and VIII: right anterior duct (RAD), coursing

more vertically

•right posterior and anterior ducts unite to from the right

hepatic duct (RHD)

•segmental bile ducts from II-to-IV unite to form the left

hepatic duct (LHD)

The left and right hepatic ducts unite to form the common

hepatic duct (CHD).

Bile duct(s) from segment I drain into the angle of their

union.

.

1. Castaing D. Surgical anatomy of the biliary tract. (2008) HPB : the official journal of the International Hepato Pancreato Biliary Association. 10 (2): 72-6.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-4-2048.jpg)

![TERMINOLOGY & CLASSIFICATION: CC

• Cholangiocarcinomas (bile duct cancers) arise from the epithelial cells of the

intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. [1]

• Biliary tract cancers were traditionally divided into cancers of the GB, the extrahepatic

ducts, and the ampulla of Vater, while intrahepatic tumors were classified as primary

liver cancers.

• More recently, the term CC has been used to refer to bile duct cancers arising in

the IH, perihilar, or distal (EH) biliary tree, exclusive of GB/ AOV.

de Groen PC, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF, et al. Biliary tract cancers. N Engl J Med 1999; 341:1368.

1.Blechacz B, Gores G. Cholangiocarcinoma: Advances in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Hepatology 2008;48:308-21.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-8-2048.jpg)

![CC: Epidemiology

• CCA accounts for 10-20% of all hepatobiliary neoplasms and is the second most

common primary liver tumor.[1]

• Hepatobiliary malignancies account for 13% and 3% of overall cancer-related

mortality in the world and in the US, respectively; 10- 20% of these deaths are

caused by CC.[2]

• Mixed hepatocellularcholangiocellular carcinoma (HCC-CCA) is the newly

recognized phenotype of CCA. Mixed HCC-CCA expresses markers of

hepatocellular and biliary differentiations and represents <1% of liver tumors.

• More recently, classifying perihilar CC as a distinct entity has been proposed,

rather than grouping it with distal bile duct cancer, based on its distinct

molecular characteristics and RX.[3]

1. Shaib Y, El-Serag HB: The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 24:115–125, 2004.

2. Tyson GL, El-Serag HB. Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 2011; 54:173-84.

3. Andersen JB, Spee B, Blechacz BR, et al. Genomic and genetic characterization of cholangiocarcinoma identifies therapeutic targets for tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Gastroenterology 2012; 142:1021-31 e15.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-10-2048.jpg)

![Epidemiology

• The incidence of intrahepatic CCA varies across the world.[1]

• It is highest in northeast Thailand (96 per 100,000 men and 38 per 100,000

women), probably due to the high prevalence of liver-fluke infestations.

• In the past, the average age of DX of IHCCA was in the mid-50s, but there has

been a recent shift in age of DX towards the mid-60s. This observation might

relate to:

(1) development of CCA in the context of ever-increasing CLD in the aging

population

(2) improved DX, follow-up, and MX of RF(i.e., PSC, choledochal cysts) in younger

individuals.

• 52-54% of pts with CC are male. CC is uncommon before age 40 except in pts

with PSC.

1. Khan SA, et al: Changing international trends in mortality rates for liver, biliary and pancreatic tumours. J Hepatol 37:806–813, 2002.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-11-2048.jpg)

![Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

• PSC is an inflammatory disorder of the biliary tree that leads to fibrosis and

stricturing of the intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic bile ducts.

• PSC is strongly a/with UC; the incidence of colitis is around 90 % in pts with

PSC [1]. Nearly 30 % of CC are DX in pts with PSC with or without UC,

within 2 years of the DX of PSC.(zakim)

• The annual incidence of CC in pts with PSC has been estimated to be

between 0.6 and 1.5 %/yr, with a lifetime risk of 10-15 %[2-8].

• CC develops at a significantly younger age (between the ages of 30 and 50)

in pts with PSC than in pts without this condition. [9].

1. Tung BY, Brentnall T, Kowdley KV, et al. Diagnosis and prevalence of ulcerative colitis in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (abstract). Hepatology 1996; 24:169A.

2. Bergquist A, Ekbom A, Olsson R, et al. Hepatic and extrahepatic malignancies in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol 2002; 36:321.

3. Lee YM, Kaplan MM. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. N Engl J Med 1995; 332:924.

4. Wiesner RH. Current concepts in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Mayo Clin Proc 1994; 69:969.

5. Bergquist A, Glaumann H, Persson B, Broomé U. Risk factors and clinical presentation of hepatobiliary carcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a case-control study. Hepatology 1998; 27:311.

6. de Groen PC. Cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis: who is at risk and how do we screen? Hepatology 2000; 31:247.

7. Burak K, Angulo P, Pasha TM, et al. Incidence and risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99:523.

8. Claessen MM, Vleggaar FP, Tytgat KM, et al. High lifetime risk of cancer in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol 2009; 50:158.

9. LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH, Ludwig J, MacCarty RL. Current concepts. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. N Engl J Med 1984; 310:899.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-13-2048.jpg)

![RF for the development of CC in pts with PSC

• Alcohol consumption has been suggested to be a RF for the development of

CC in pts with PSC [1].

• Link between smoking and CC in PSC has not been confirmed[2].

• The efficacy of tumor markers as screening tests for CC in pts with PSC has

not been established.

• In one 3-yr prospective study of 75 pts with PSC without clinical signs of CC,

serum levels of CEA, CA 19-9 were not useful in diagnosing bile duct cancer

because of limited SP [3].

• By contrast, a more recent study of 208 pts found a SN, SP, PPV and NPV of

78, 98, 56 and 99 %, respectively, using an CA 19-9 level of 129 U/ml [4].

1. Bergquist A, Glaumann H, Persson B, Broomé U. Risk factors and clinical presentation of hepatobiliary carcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a case-control study. Hepatology 1998; 27:311.

2. Chalasani N, Baluyut A, Ismail A, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a multicenter case-control study. Hepatology 2000; 31:7.

3. Hultcrantz R, Olsson R, Danielsson A, et al. A 3-year prospective study on serum tumor markers used for detecting cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol 1999; 30:669.

4. Levy C, Lymp J, Angulo P, et al. The value of serum CA 19-9 in predicting cholangiocarcinomas in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Dis Sci 2005; 50:1734.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-14-2048.jpg)

![Fibropolycystic liver disease

• Congenital abnormalities of the biliary tree (Caroli's syndrome, congenital

hepatic fibrosis, choledochal cysts) carry an approx 15 % risk of malignant

change (average age at DX 34) [1-3].

• Choledochal cysts are congenital cystic dilatations of the bile ducts, while

Caroli's disease is a variant of choledochal cyst disease that is characterized

by multiple cystic dilations of the intrahepatic biliary ducts [4]. The overall

incidence of CC in pts with untreated cysts is as high as 28 % [2,3].

• Although the mechanism underlying carcinogenesis in these pts is unclear, it

could be related to biliary stasis, chronic inflammation from reflux of

pancreatic juice, or abnormalities in bile salt transporter proteins [1].

• Cyst excision reduces but does not eliminate the risk for developing CC.[5]

1. Khan SA, Thomas HC, Davidson BR, Taylor-Robinson SD. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet 2005; 366:1303.

2. Scott J, Shousha S, Thomas HC, Sherlock S. Bile duct carcinoma: a late complication of congenital hepatic fibrosis. Case report and review of literature. Am J Gastroenterol 1980; 73:113.

3. Lipsett PA, Pitt HA, Colombani PM, et al. Choledochal cyst disease. A changing pattern of presentation. Ann Surg 1994; 220:644.

4. Dayton MT, Longmire WP Jr, Tompkins RK. Caroli's Disease: a premalignant condition? Am J Surg 1983; 145:41.

5. Tyson GL, El-Serag HB. Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology 2011; 54:173-84.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-15-2048.jpg)

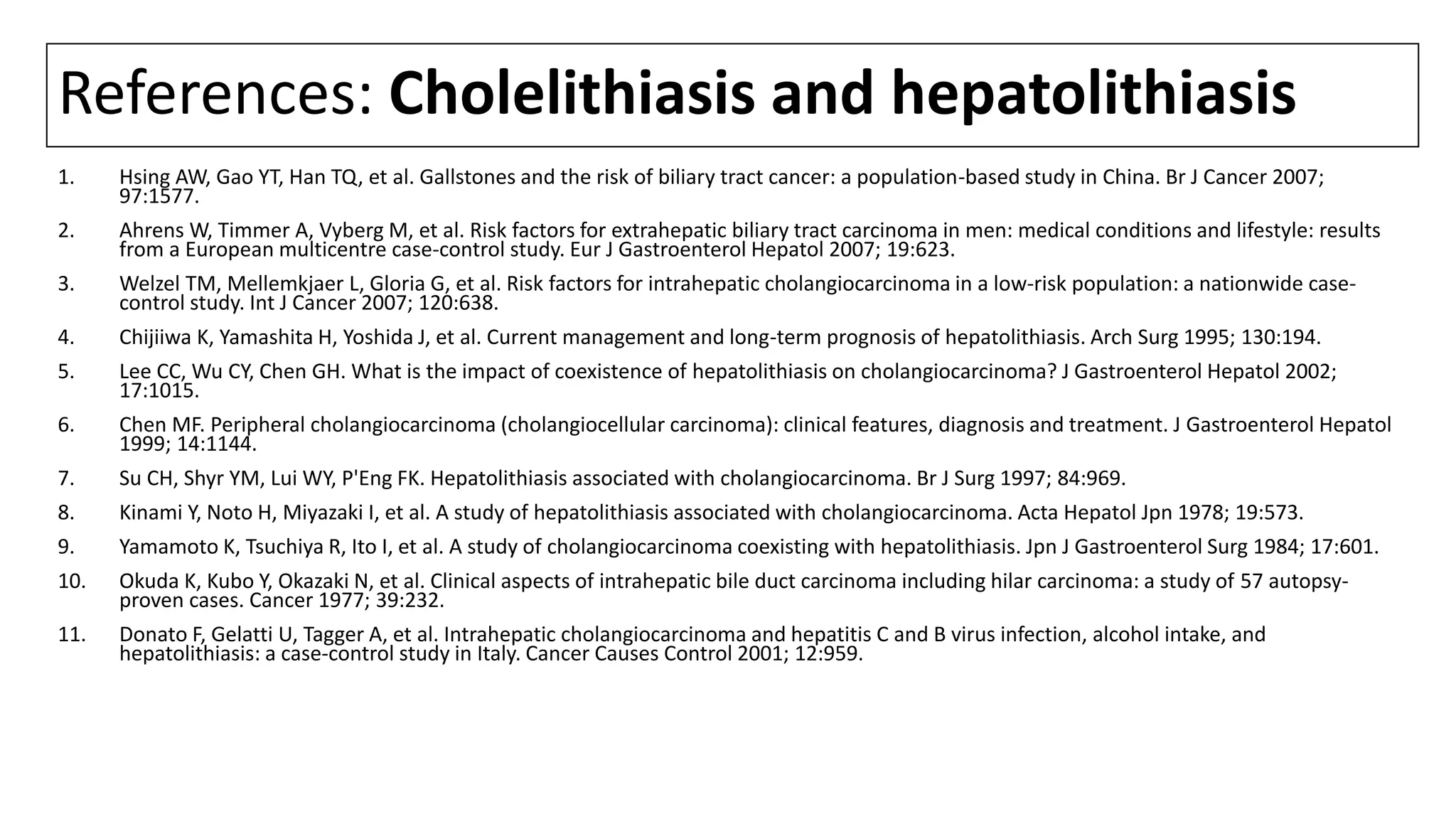

![Cholelithiasis and hepatolithiasis

• While cholelithiasis is a well-described strong RF for GB cancer, the

association between gallstones and CC is less well established. However, at

least three epidemiologic studies note an ↑ risk for CC among pts with

symptomatic gallstone disease, but of a lower magnitude than for GB

cancer [1-3].

• There is clear & strong association betwn chronic intrahepatic stone

disease (hepatolithiasis,aka recurrent pyogenic cholangitis) & IHCC [4-11].

• In Taiwan, 50-70 % of pts undergoing resection for CC have associated

hepatolithiasis [6,7], while in Japan, the incidence is much lower (6-18 %)

[8,9,10].

References are at the end of the slides.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-16-2048.jpg)

![Cholelithiasis and hepatolithiasis

• The etiology of hepatolithiasis is not known, but congenital ductal

abnormalities, and chronic inflammation from bacterial or parasitic

infections have all been implicated. The calculi are usually composed of

calcium bilirubinate (brown pigment stones) rather than cholesterol. The

biliary stones are thought to cause bile stasis, predisposing to recurrent

bacterial infections and chronic inflammation.

• It may be difficult to identify CC arising as a complication of hepatolithiasis.

However, the DX should be suspected in a pt over the age of 40 who has a

long history of hepatolithiasis, weight loss, ↑ alk phosphatase, a serum

CEA >4.2 ng/mL[1].

1. Kim YT, Byun JS, Kim J, et al. Factors predicting concurrent cholangiocarcinomas associated with hepatolithiasis. Hepatogastroenterology 2003; 50:8.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-17-2048.jpg)

![Toxic exposures

• A clear association exists between exposure to the radiologic contrast agent

Thorotrast (a radiologic contrast agent banned in the 1960s for its

carcinogenic properties) and subsequent CC; malignancy usually develops

30 to 35 years after exposure [1].

• An increased incidence of CC has been less strongly a/with several

occupations, including the auto, rubber, chemical, and wood-finishing

industries.

• In addition, toxins like dioxin and polyvinyl chloride have been postulated

to contribute to development of CCA.

1. Sahani D, Prasad SR, Tannabe KK, et al. Thorotrast-induced cholangiocarcinoma: case report. Abdom Imaging 2003; 28:72.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-19-2048.jpg)

![Lynch syndrome and Biliary papillomatosis

• At least two genetic disorders are a/with an increased risk of CC: Lynch

syndrome, and a rare inherited disorder called multiple biliary

papillomatosis [1].

• Multiple biliary papillomatosis is characterized by multiple adenomatous

polyps in the bile ducts, and repeated episodes of abdominal pain,

jaundice, and acute cholangitis [2].

• Biliary papillomatosis should be considered a premalignant condition since

a high proportion of these lesions (83 % in one study [2]) undergo

malignant transformation [3].

1. Mecklin JP, Järvinen HJ, Virolainen M. The association between cholangiocarcinoma and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 1992; 69:1112.

2. Lee SS, Kim MH, Lee SK, et al. Clinicopathologic review of 58 patients with biliary papillomatosis. Cancer 2004; 100:783.

3. Taguchi J, Yasunaga M, Kojiro M, et al. Intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary papillomatosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1993; 117:944.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-20-2048.jpg)

![Viral hepatitis

• An association between HCV and CC was initially suggested in 1991 [1].

• Since then, several reports have noted a higher than expected rate of HCV-

associated cirrhosis in pts with CC, although the risk is much lower than for

HCC[2-10].

• A prospective case control study from Japan reported the risk of developing

CC in pts with cirrhosis related to HCV was 3.5 % at 10 years [5].

• An association between HBV and CC has also been suggested, although the

data are less compelling than for HCV.

References are at the end of the slides.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-21-2048.jpg)

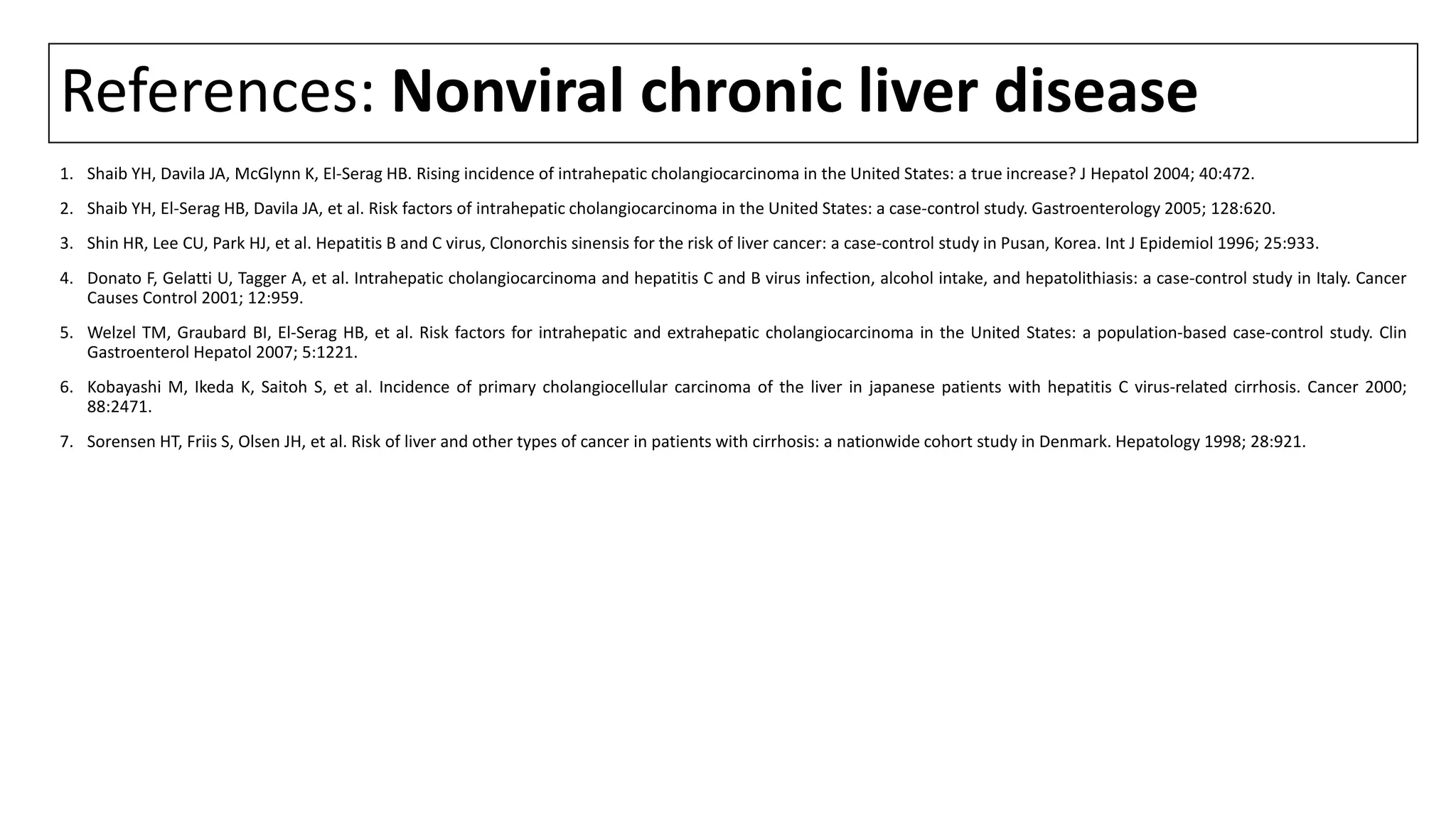

![Nonviral chronic liver disease

• As with HCC, CLD of nonviral etiology also appears to be a/with IHCC[ 1-7].

• In a case-control study, RF that were significantly more prevalent among

pts with IHCC included nonspecific cirrhosis (adjusted OR 27.2) and

ALD(adjusted OR 7.4) [2].

• A Danish cohort study that followed 11,605 persons with cirrhosis from

any cause for an average of approx 6 yrs found a significant 10X higher risk

for IHCC among these pts compared to the general population [7].

References are at the end of the slides.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-22-2048.jpg)

![Diabetes

• An association between DM and cancer of the biliary tract has been

suggested in several case-control and cohort studies.

• In a meta-analysis of 15 such studies, individuals with DM had a significantly

increased risk of CC relative to non-diabetics (RR 1.60) [1]. The risk was

significantly elevated for both intrahepatic and extrahepatic CC.

1. Jing W, Jin G, Zhou X, et al. Diabetes mellitus and increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer Prev 2012; 21:24.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-23-2048.jpg)

![OTHERS

• Obesity — Obesity was linked to extrahepatic CC in a population-based

case-control study [1].

• Metabolic syndrome — A study that included 743 pts with IHCC found that

the presence of the metabolic syndrome, (defined by the presence of three

of the following: elevated waist circumference/central obesity, dyslipidemia,

HTN, or IFG) was a RF for IHCC [2].

1. Welzel TM, Graubard BI, El-Serag HB, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a population-based case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;

5:1221.

2. Welzel TM, Graubard BI, Zeuzem S, et al. Metabolic syndrome increases the risk of primary liver cancer in the United States: a study in the SEER-Medicare database. Hepatology 2011; 54:463.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-24-2048.jpg)

![HIV infection

• HIV infection was an independent RF for IHCC in the Medicare population

in the case control study[1].

• However, the validity of the association is uncertain given the relatively

small number of cases that were identified and the possibility that at least

some of the HIV infected cases may have had coexisting, undiagnosed risk

factors (such as HCV infection).

1. Shaib YH, El-Serag HB, Davila JA, et al. Risk factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a case-control study. Gastroenterology 2005; 128:620.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-25-2048.jpg)

![Pathology

• Macroscopically, it can be described according to its

growth characteristics as mass forming, periductal-

infiltrating, or intraductal-papillary.

• IHCC are typically mass forming, whereas perihilar

carcinomas most commonly display a periductal-infiltrating

growth pattern.[1]

• The mass-forming type tends to invade the hepatic

parenchyma, with invasion of the lymphatics at advanced

stages, whereas the periductal-infiltrating type spreads

along the Glisson sheath via the lymphatics.[1]

• Intraductal-papillary spread superficially along the biliary

mucosa without deep invasion of the fibromuscular wall

layers .Good Prognosis than non papillary types.

1. Blechacz B, Komuta M, Roskams T, et al. Clinical diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 8:512-22.

2. Patel T. Cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 3(1), 33–42(2006) Taken from medcape. Ref:2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-26-2048.jpg)

![Pathology

• The majority of CC (>90 %) are adenocarcinomas, with squamous cell

carcinoma being responsible for most of the remaining cases. They are

graded as well, moderately or poorly differentiated.

• Adenocarcinomas are further divided into three types: nodular, sclerosing,

and papillary.

• Sclerosing — Sclerosing (scirrhous) tumors tend to invade the bile duct

wall early, and as a result, are a/with low resectability and cure rates.

Unfortunately, most CC are of this type.

• In one report, 94% of 194 perihilar tumors were sclerotic adenocarcinomas.

[1].

1. Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg 1996; 224:463.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-27-2048.jpg)

![Pathology

• Nodular — present as a constricting annular lesion of the bile duct. These

are highly invasive tumors, and most pts have advanced disease at the time

of DX; thus, the resectability and cure rates are very low.

• Papillary — rarest form of CC. These usually present as bulky masses in

the CBD lumen which cause biliary obstruction early in the course of the

disease, So they have the highest resectability & cure rates [1,2].

• Characteristics that are common to all three tumor types include slow

growth, a high rate of local invasion, mucin production, and a tendency to

invade perineural sheaths and spread along nerves. In contrast distant

metastases are distinctly uncommon in cholangiocarcinoma.

1. Jarnagin WR, Bowne W, Klimstra DS, et al. Papillary phenotype confers improved survival after resection of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2005; 241:703.

2. Martin RC, Klimstra DS, Schwartz L, et al. Hepatic intraductal oncocytic papillary carcinoma. Cancer 2002; 95:2180.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-28-2048.jpg)

![Pathology

• Other histologic types include intestinal-type adenocarcinoma, clear cell

adenocarcinoma, signet-ring cell carcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma,

squamous cell carcinoma, and small cell carcinoma.[1]

1. Blechacz B, Gores G. Cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Liver Dis 2008; 12:131-50.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-29-2048.jpg)

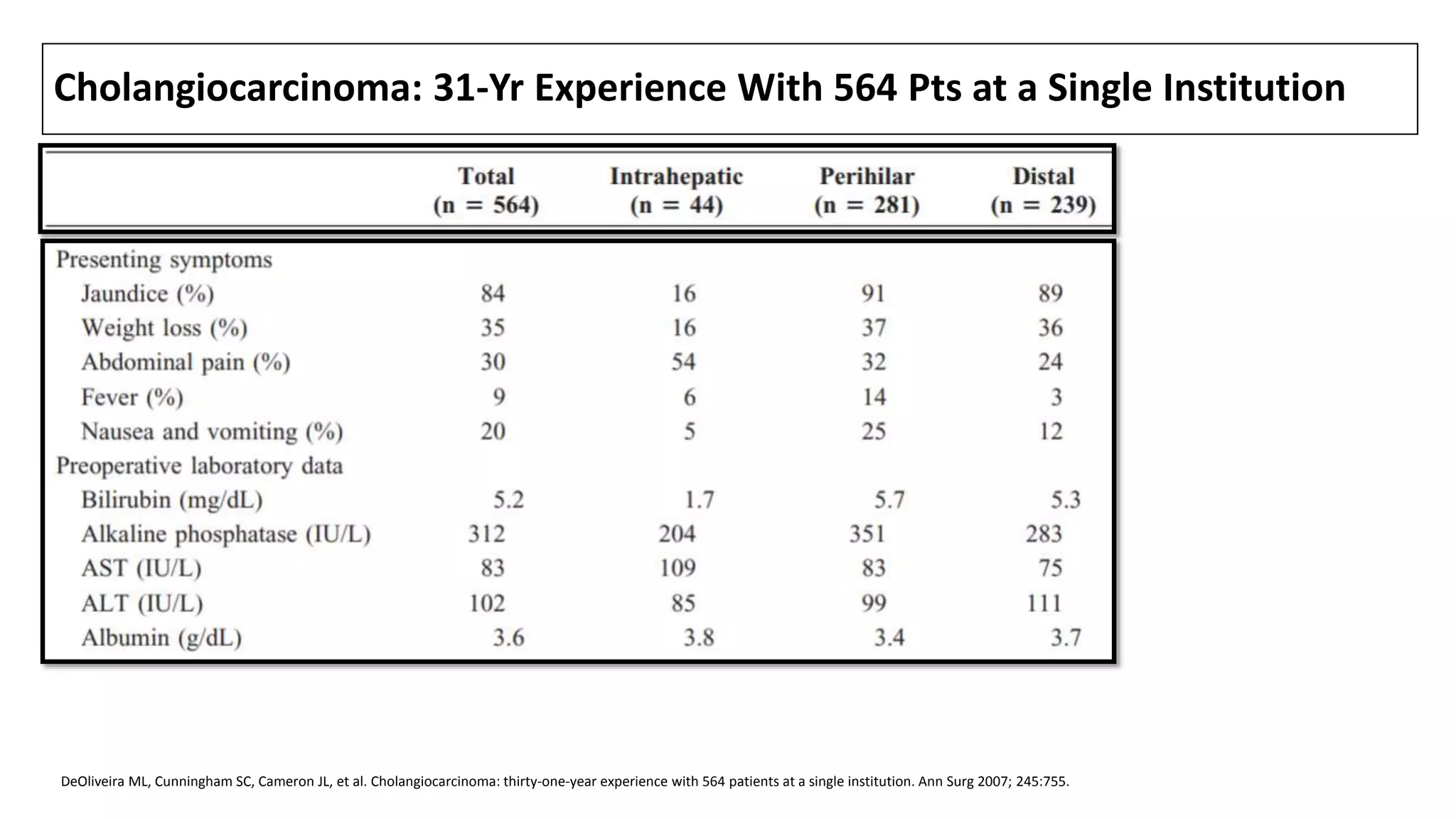

![CLINICAL FEATURES

• CC usually become symptomatic when the tumor obstructs the biliary

drainage system, causing painless jaundice.

• Common symptoms include pruritus (66 %), abdominal pain (30 to 50 %),

weight loss (30 to 50 %), and fever (up to 20 %) [1,2].

• The pain is generally described as a constant dull ache in the RUQ.

• Cholangitis is an unusual presentation. Pts with PSC and CC tend to present

with a declining performances status and increasing cholestasis.

• Other symptoms related to biliary obstruction include clay-colored stools

and dark urine.

• Physical signs include jaundice (90 %), hepatomegaly (25-40 %), or a right

upper quadrant mass (10 %) [1].

1. Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg 1996; 224:463.

2. Nagorney DM, Donohue JH, Farnell MB, et al. Outcomes after curative resections of cholangiocarcinoma. Arch Surg 1993; 128:871.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-30-2048.jpg)

![CLINICAL FEATURES

• Laboratory studies typically suggest biliary obstruction, with elevations in

total (often >10 mg/dL) and direct bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase (usually

increased two- to 10-fold), 5'-nucleotidase, and GGT.

• Transaminase levels (AST and ALT) may be initially normal; chronic biliary

obstruction often leads to liver dysfunction and a pattern consistent with

injury, with elevated AT and a prolonged PT.

• CC involving only the intrahepatic ducts (<10 % of all CC [1]) may present

differently. Affected pts are less likely to be jaundiced. Instead, they usually

have a history of dull RUQ pain and weight loss, an elevated serum alk

phosphatase, and normal or only slightly elevated serum bilirubin levels.

1. DeOliveira ML, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg 2007; 245:755.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-33-2048.jpg)

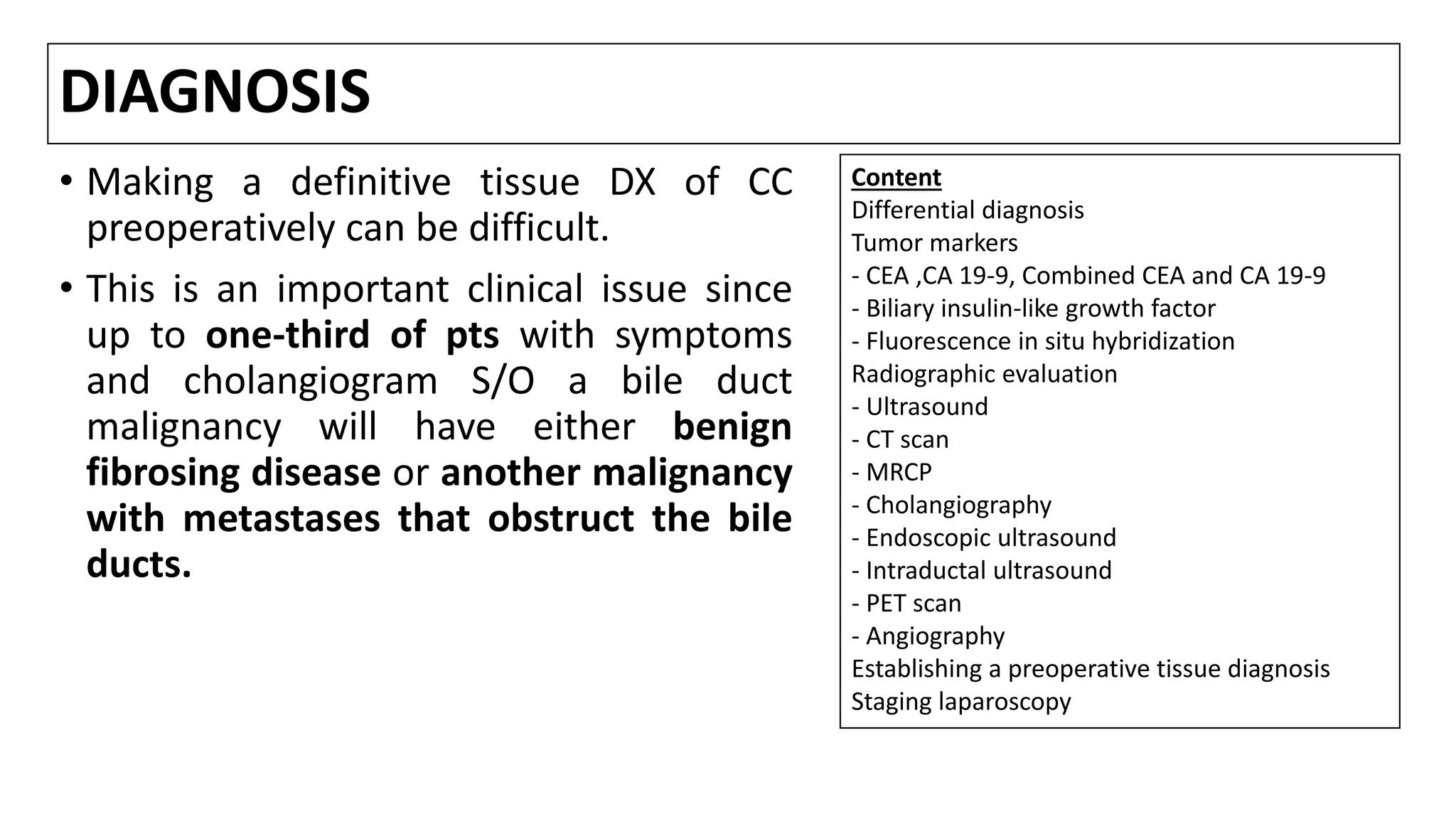

![Differential diagnosis

• While the triad of cholestasis, abdominal pain, and weight loss is suggestive of

either a hepatobiliary or pancreatic malignancy, the DD includes

choledocholithiasis, benign bile duct strictures (usually postop), sclerosing

cholangitis, or compression of the CBD by either CP or pancreatic cancer.

• Up to one-third of pts with symptoms and cholangiogram suggestive of a bile

duct malignancy will have either benign fibrosing disease or another

malignancy with metastases that obstruct the bile ducts [1,2 ].

• Liver biochemical tests are of little use in differentiating among these conditions

since all can be a/with jaundice and an elevated alkaline phosphatase.

• One useful clinical finding is that CC is often a/with intermittent rather than

steadily progressive jaundice.

1. Wetter LA, Ring EJ, Pellegrini CA, Way LW. Differential diagnosis of sclerosing cholangiocarcinomas of the common hepatic duct (Klatskin tumors). Am J Surg 1991; 161:57.

2. Verbeek PC, van Leeuwen DJ, de Wit LT, et al. Benign fibrosing disease at the hepatic confluence mimicking Klatskin tumors. Surgery 1992; 112:866.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-35-2048.jpg)

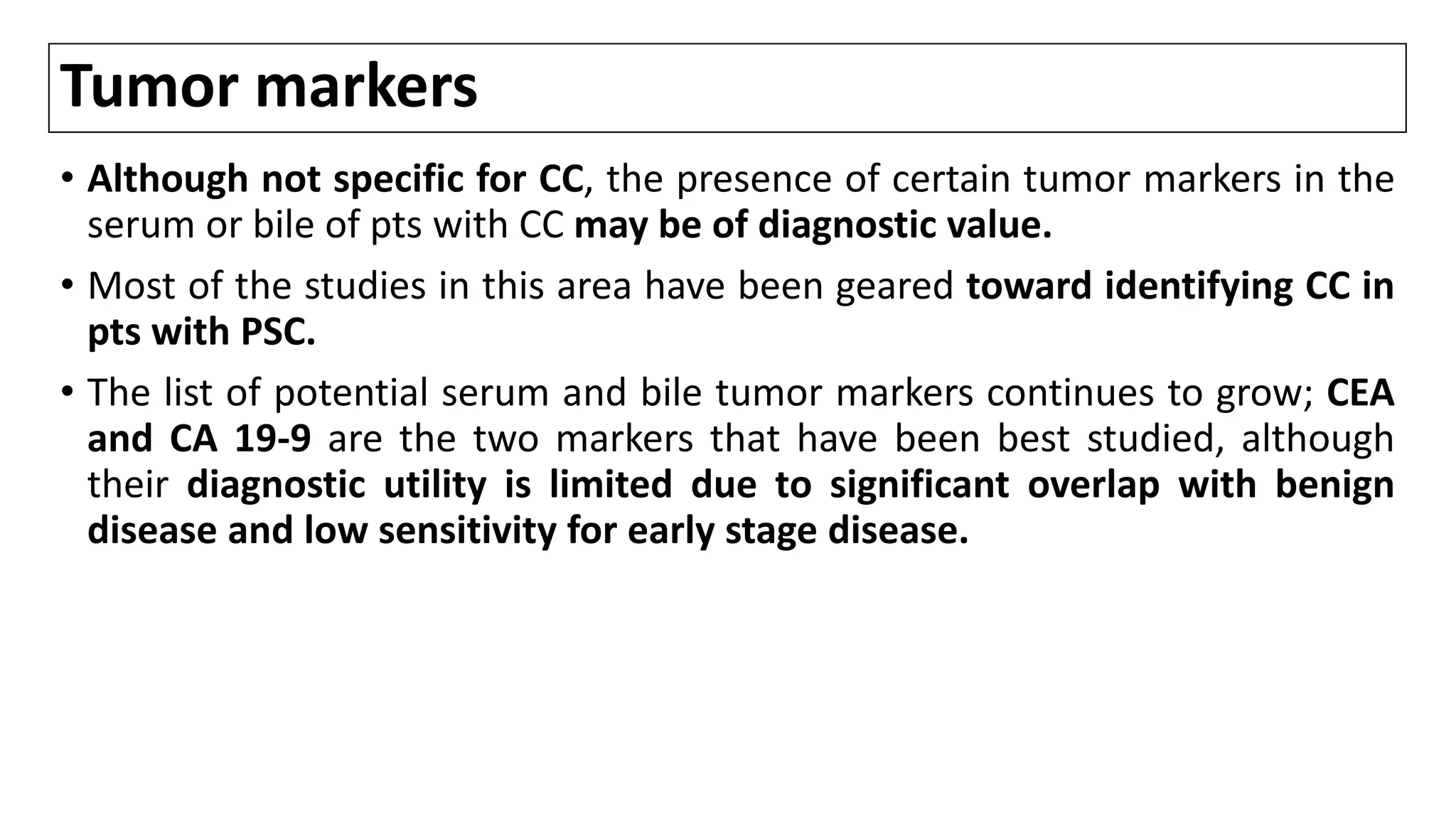

![Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA)

• Serum levels of CEA are neither sufficiently sensitive nor specific to DX CC.

Many conditions other than CC can ↑ serum levels of CEA.

• Noncancer-related causes of an elevated CEA include gastritis, PUD,

diverticulitis, liver disease, COPD, DM, and any acute or chronic

inflammatory state.

• One large series evaluated serum CEA levels in 333 pts with PSC, of whom 44

(13 %) were DX with CC either by histologic confirmation or at least 1 year of

clinical follow-up [1]. A serum CEA level >5.2 ng/mL had a SN and SP of 68

and 82 % respectively.

1. Siqueira E, Schoen RE, Silverman W, et al. Detecting cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56:40.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-37-2048.jpg)

![Cancer antigen (CA) 19-9

• Serum levels of CA 19-9 are widely used, particularly for detecting CC in pts

with PSC.

However, there are limitations to the use of serum CA 19-9 as a tumor marker

for CC in this setting, as evidenced by the following:

• The SP of CA 19-9 is limited. CA 19-9 is frequently elevated in pts with

various benign pancreaticobiliary disorders, including cholangitis, and other

malignancies, including pancreatic .

• In a series, a level of >180 U/mL had a SN of only 67 %; the SP of 98 % [1].

1. Siqueira E, Schoen RE, Silverman W, et al. Detecting cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56:40.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-38-2048.jpg)

![Cancer antigen (CA) 19-9

• The optimal cutoff value is influenced by the presence of cholangitis and

cholestasis.

• In one report, cutoff value of ≥37 U/mL was 78 % SN and 83 % SP for malignant

disease in pts with neither cholangitis or cholestasis [1].

• In contrast, using the same cutoff in the presence of either condition ↓ the SP to

only 42 %. In pts with cholestasis/cholangitis, increasing the cutoff value to ≥300

U/mL was optimal for increasing SP (87 %) but at the expense of SN (approx 40 %).

• Thus, in pts with symptoms of acute cholangitis, serum CA 19-9 should ideally be

reevaluated after recovery.

• Most typically use a CA 19-9 value ≥200 U/mL to increase suspicion for a CC in pts

with PSC, especially in the presence of a dominant hilar stricture.

• If initially elevated, serum CA 19-9 levels may also be useful for following the

effect of treatment and to detect disease recurrence.

1. Kim HJ, Kim MH, Myung SJ, et al. A new strategy for the application of CA19-9 in the differentiation of pancreaticobiliary cancer: analysis using a receiver operating characteristic curve. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;

94:1941.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-39-2048.jpg)

![Combined CEA and CA 19-9

• The use of a combined index of serum CA 19-9 & CEA has been

proposed[1].

• In one series, this index correctly identified 10 of 15 pts with CC, including 6

of 11 with radiographically occult disease; there were no false positives.

• However, in a more recent study of 72 pts with PSC, the use of CA 19-9

alone (cutoff value ≥37 U/mL) was 63 % SN for detecting CC, while the SN

of the combined CA 19-9 /CEA index was only 33 % [2].

• In the series focused on individuals with PSC [3], 45 pts (8 of whom had

CC) had both tests. Using the cutoff values of CEA >5.2 ng/mL and CA 19-9

>180 U/mL, the SN and SP were 100%and 78%respectively.

1. Ramage JK, Donaghy A, Farrant JM, et al. Serum tumor markers for the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology 1995; 108:865.

2. Björnsson E, Kilander A, Olsson R. CA 19-9 and CEA are unreliable markers for cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Liver 1999; 19:501.

3. Nakeeb A, Lipsett PA, Lillemoe KD, et al. Biliary carcinoembryonic antigen levels are a marker for cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg 1996; 171:147.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-40-2048.jpg)

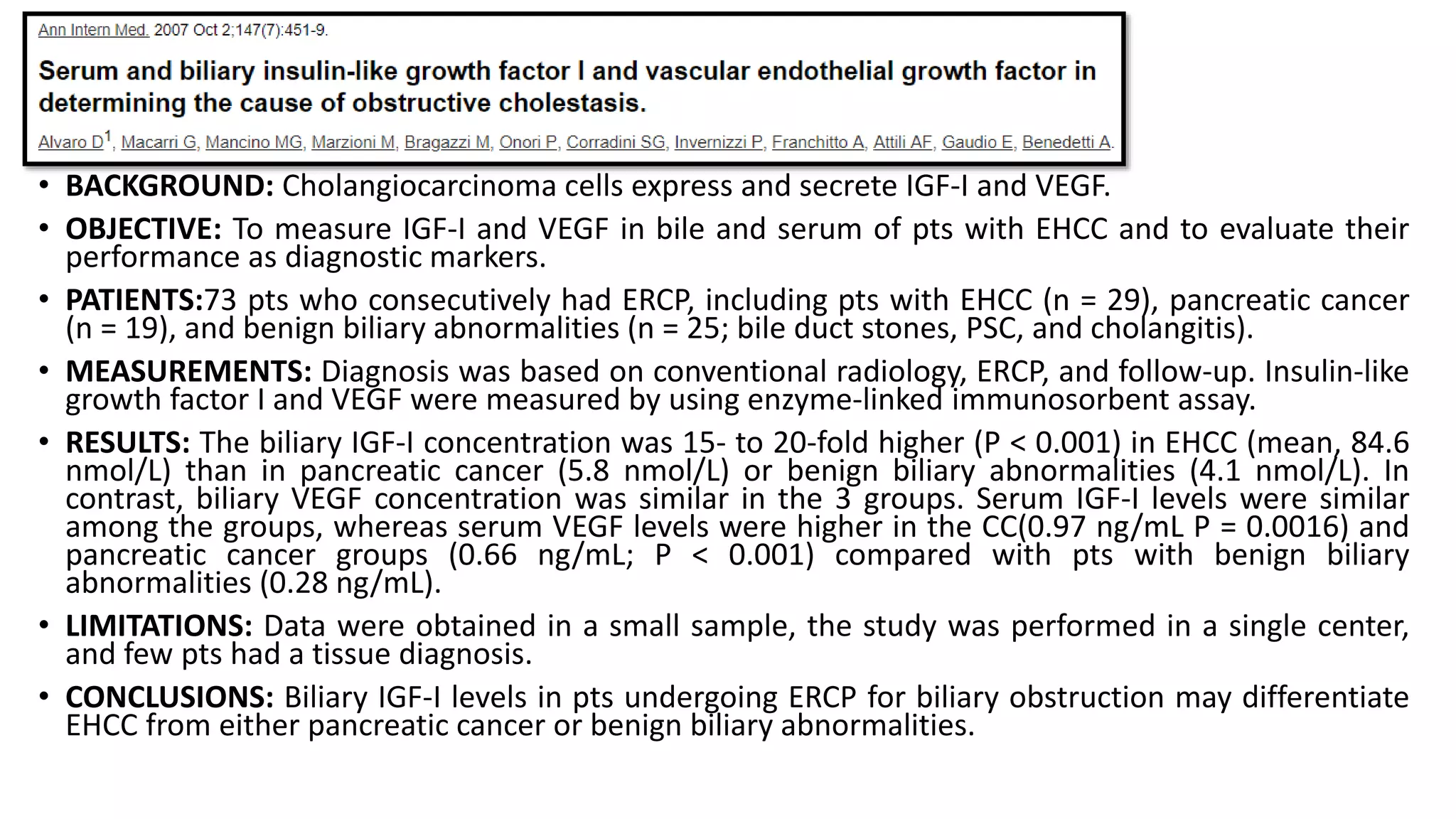

![Biliary insulin-like growth factor

• CC cells secrete insulin-like growth factor I making it potentially useful for

DX.

• A pilot study found that biliary levels were highly accurate in discriminating

EHCC from PC and benign biliary abnormalities [1].

• Additional studies are needed to validate these findings.

1. Alvaro D, Macarri G, Mancino MG, et al. Serum and biliary insulin-like growth factor I and vascular endothelial growth factor in determining the cause of obstructive cholestasis. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147:451.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-41-2048.jpg)

![Fluorescence in situ hybridization

• In a large study of 498 consecutive pts undergoing ERC for pancreatobiliary

strictures, polysomy of FISH had high SN (42.9%) compared with routine

cytology (20.1%) and both tests displayed identical SP. [1,2]

• SN for detection of perihilar CCA is 38-58% as compared with 15% SN of

conventional cytology.[3]

• Serial polysomy, especially in combination with CA19-9 ≥129 U/mL, is a

strong predictor of CCA development and precedes DX of CCA by imaging

studies by 2.7 yrs.[4,5]

1. Fritcher EG, et al: A multivariable model using advanced cytologic methods for the evaluation of indeterminate pancreatobiliary strictures. Gastroenterology 136:2180–2186, 2009.

2. Moreno Luna LE, et al: Advanced cytologic techniques for the detection of malignant pancreatobiliary strictures. Gastroenterology 131:1064–1072, 2006.

3. Sinakos E, et al: Many patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and increased serum levels of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 do not have cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 9:434–439 e1, 2011.

4. Barr Fritcher EG, et al: Primary sclerosing cholangitis with equivocal cytology: fluorescence in situ hybridization and serum CA 19-9 predict risk of malignancy. Cancer Cytopathol 121:708–717, 2013.

5. Barr Fritcher EG, et al: Primary sclerosing cholangitis patients with serial polysomy fluorescence in situ hybridization results are at increased risk of cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol 106:2023–2028, 2011.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-45-2048.jpg)

![Ultrasound

• The diagnostic accuracy of US was shown in a study of 429 pts who presented

with obstructive jaundice over a 10 yr period [1]. US demonstrated ductal

obstruction in 89%, and its SN for localizing the site of obstruction was 94 %.

• IHCC appear as a mass lesion on US.

• Perihilar and extrahepatic cancers may not be detected, especially if small, but

indirect signs (ductal dilatation throughout the obstructed liver segments) may

point toward the DX.

• An obstructing lesion is suggested by ductal dilatation (>6 mm in normal adults)

in the absence of stones.

• Proximal lesions cause dilation of the intrahepatic ducts alone, while both

intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts are dilated with more distal lesions [2]. The

exact location of the tumor can be suggested if there is an abrupt change in

ductal diameter.

1. Sharma MP, Ahuja V. Aetiological spectrum of obstructive jaundice and diagnostic ability of ultrasonography: a clinician's perspective. Trop Gastroenterol 1999; 20:167.

2. Saini S. Imaging of the hepatobiliary tract. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:1889.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-47-2048.jpg)

![Ultrasound

• An important adjunct to diagnostic US is the ability to evaluate vascular

involvement (ie, compression, encasement, or thrombosis of the PV,

encasement or occlusion of the HA) using ultrasound color Doppler.

• Invasion into the portal vein or hepatic artery is an important indicator of

unresectability.

• In one report, preoperative US detected 13 of 16 cases involving the

hepatic vein (81% SN, 97% SP, and 87% PPV) [1]. These results were

comparable to those found during MRI (75% SN).

• In a second series of 41 pts with CC and demonstrated PV involvement at

surgery, US detected 38 preoperatively (93% SN, 99% SP, respectively) [2].

These results were comparable to those found by angiography with

computed tomographic arterial portography (CTAP, 90 %SN).

1. Hann LE, Schwartz LH, Panicek DM, et al. Tumor involvement in hepatic veins: comparison of MR imaging and US for preoperative assessment. Radiology 1998; 206:651.

2. Bach AM, Hann LE, Brown KT, et al. Portal vein evaluation with US: comparison to angiography combined with CT arterial portography. Radiology 1996; 201:149.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-48-2048.jpg)

![CT scan

A distended GB with dilated intrahepatic and extrahepatic ducts is more

typical of tumors involving the CBD, the AOV, or PC. Although CC is generally

less common than PC, it should be suspected in a pt with a specific RF (eg,

PSC).

Dilatation of the ducts within an atrophied hepatic lobe, in conjunction

with a hypertrophic contralateral lobe (the atrophy-hypertrophy complex)

suggests invasion of the branch portal vein [1].

1. Hann LE, Getrajdman GI, Brown KT, et al. Hepatic lobar atrophy: association with ipsilateral portal vein obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996; 167:1017.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-50-2048.jpg)

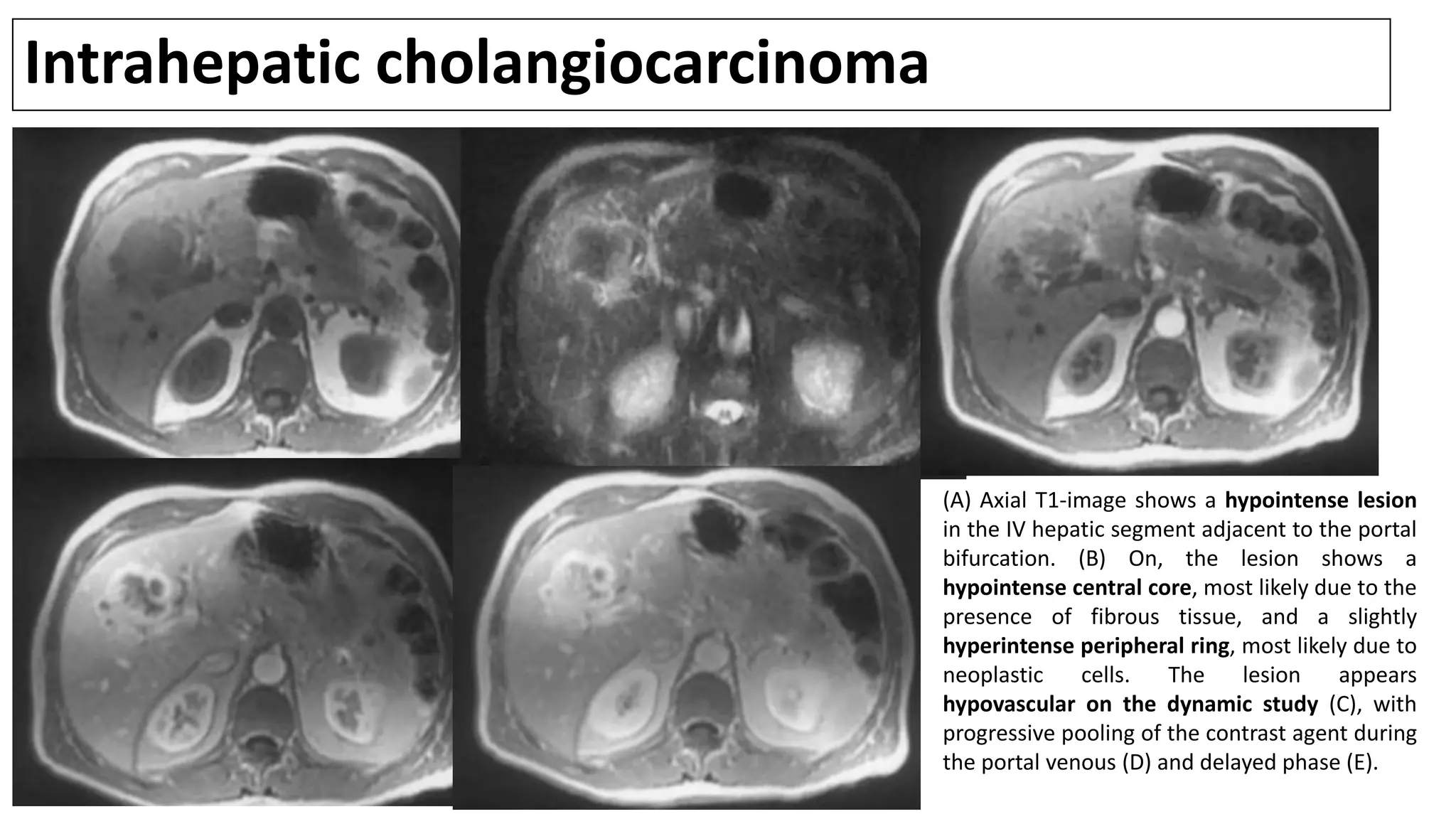

![CT scan

• CE triple phase CT is a sensitive means of distinguishing benign from malignant

intrahepatic bile duct strictures (particularly during the PVphase) and visualizing

the LN[1,2].

• Typical appearance of ICC on CT is a hypodense mass with irregular margins on

unenhanced scans, peripheral rim enhancement in the AP, and progressive

contrast uptake in the (portal-)venous and delayed contrast-enhancement

phase.

• However, some small mass-forming IHCC are arterially enhancing and may mimic

HCC[3].

• The MRI and dynamic CT images of 20 pts with IHCC were compared. The extent of

tumor enhancement was similar with both imaging methods, and biliary ductal

dilatation was detected in 65% by either method. However, the relationship of

the tumor to the vessels and surrounding organs was more easily evaluated on CT

as opposed to MRI [4].

1. Valls C, Gumà A, Puig I, et al. Intrahepatic peripheral cholangiocarcinoma: CT evaluation. Abdom Imaging 2000; 25:490.

2. Choi SH, Han JK, Lee JM, et al. Differentiating malignant from benign common bile duct stricture with multiphasic helical CT. Radiology 2005; 236:178.

3. Kim SA, Lee JM, Lee KB, et al. Intrahepatic mass-forming cholangiocarcinomas: enhancement patterns at multiphasic CT, with special emphasis on arterial enhancement pattern--correlation with clinicopathologic

findings. Radiology 2011; 260:148.

4. Zhang Y, Uchida M, Abe T, et al. Intrahepatic peripheral cholangiocarcinoma: comparison of dynamic CT and dynamic MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1999; 23:670.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-51-2048.jpg)

![CT: malignant and benign structures

• The distinction between malignant and benign structures relies on two aspects:

A: Morphology of the stricture & B: Associated findings, pointing to a cause

(As far as assessing the morphology of the stricture, modalities that image the lumen (ERCP, MRCP,

CT IVC) are best, whereas to assess for associated features US or CT/MRI are better.)

Stricture morphology

Benign features include 2:

• smooth

• tapered margins

Malignant features include:

• irregular

• shouldered margins

• thickened (>1.5 mm) and enhancing (on arterial and or portal venous phase) duct walls [1]

• It is often difficult to distinguish between malignant and benign strictures, especially if short [1].

Associated findings

Associated findings are for example:

features of chronic pancreatitis

evidence of previous cholecystectomy

lymph node enlargement

infiltrating mass

1. Choi SH, Han JK, Lee JM et-al. Differentiating malignant from benign common bile duct stricture with multiphasic helical CT. Radiology. 2005;236 (1): 178-83.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-52-2048.jpg)

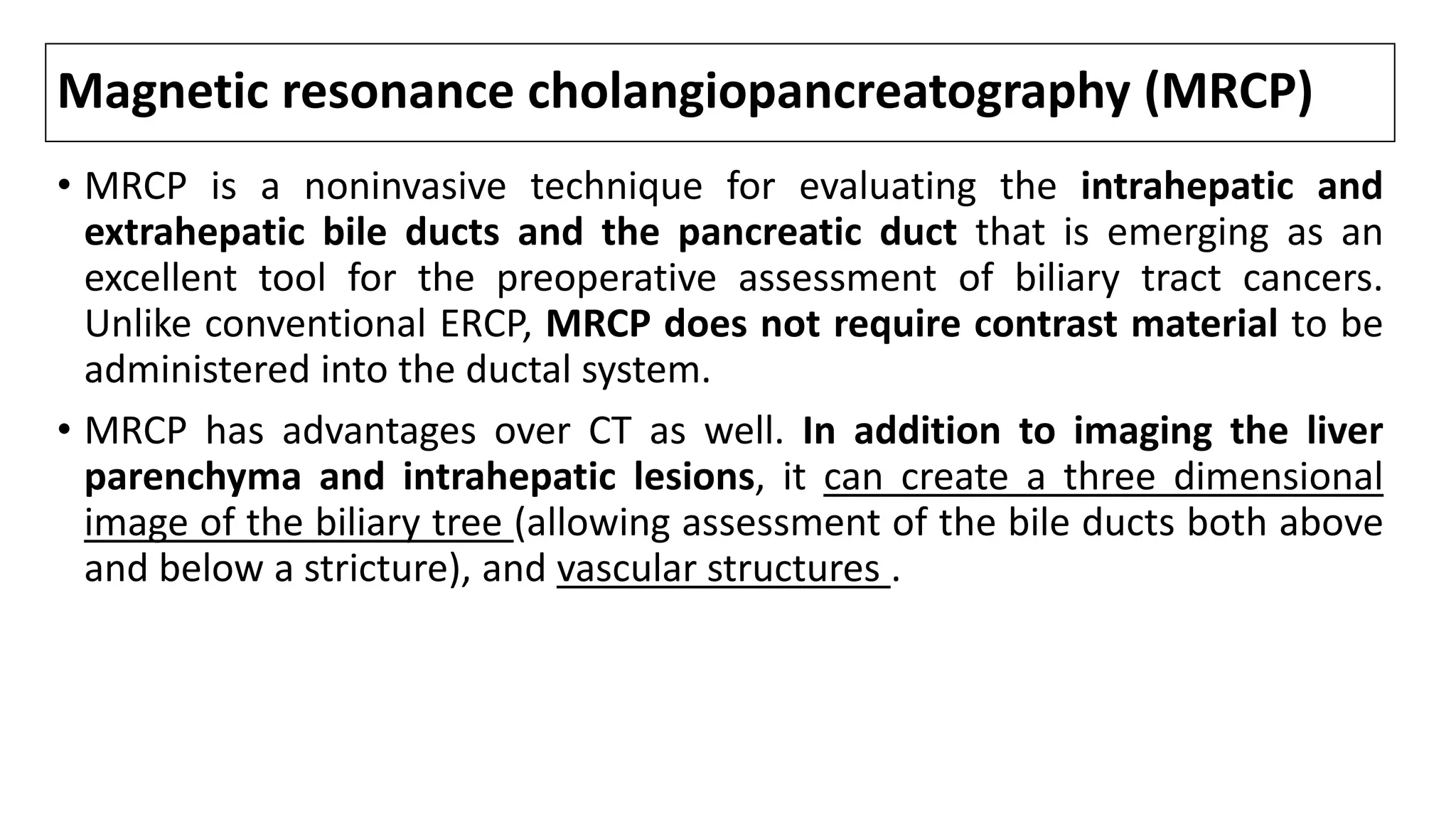

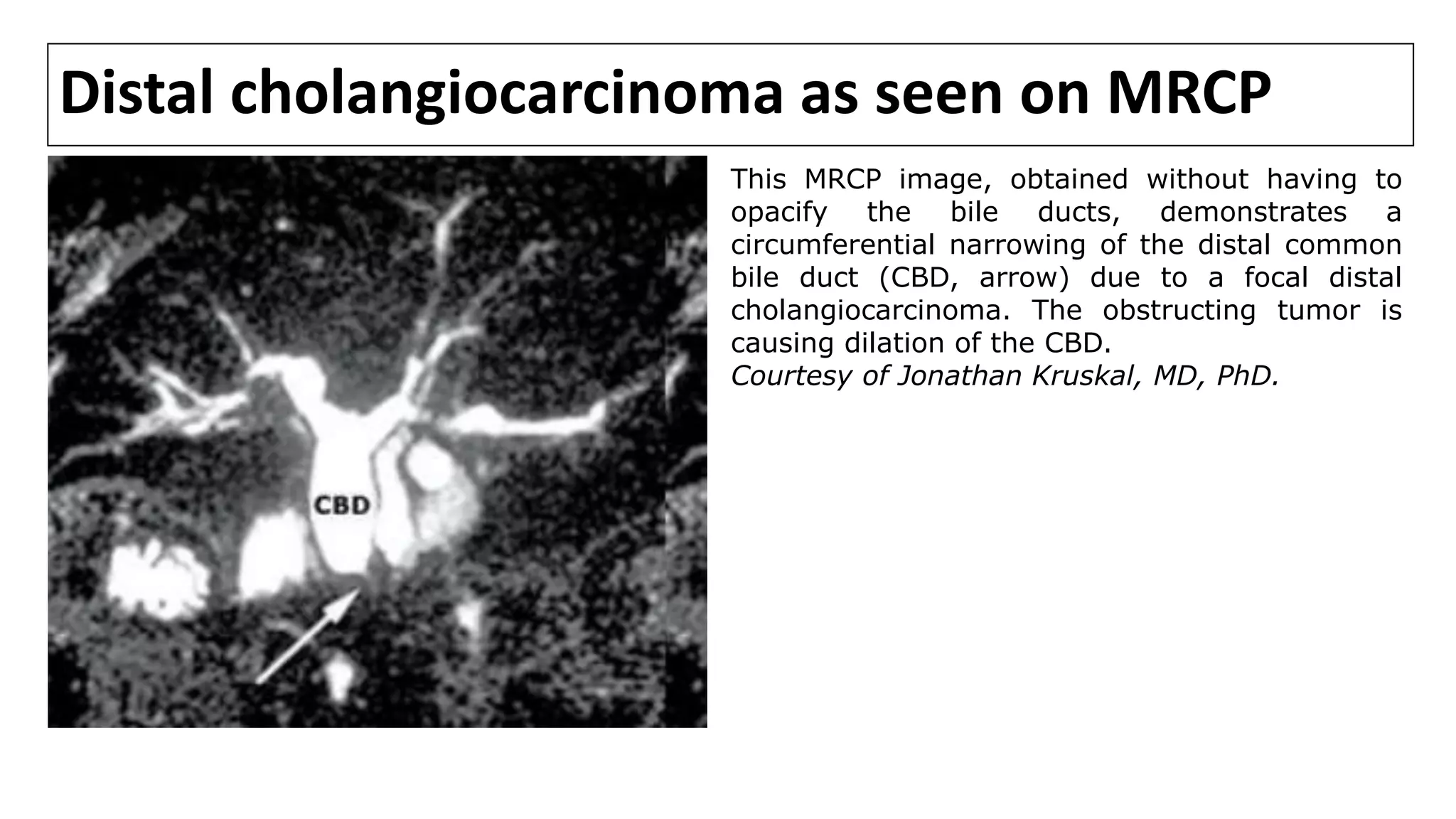

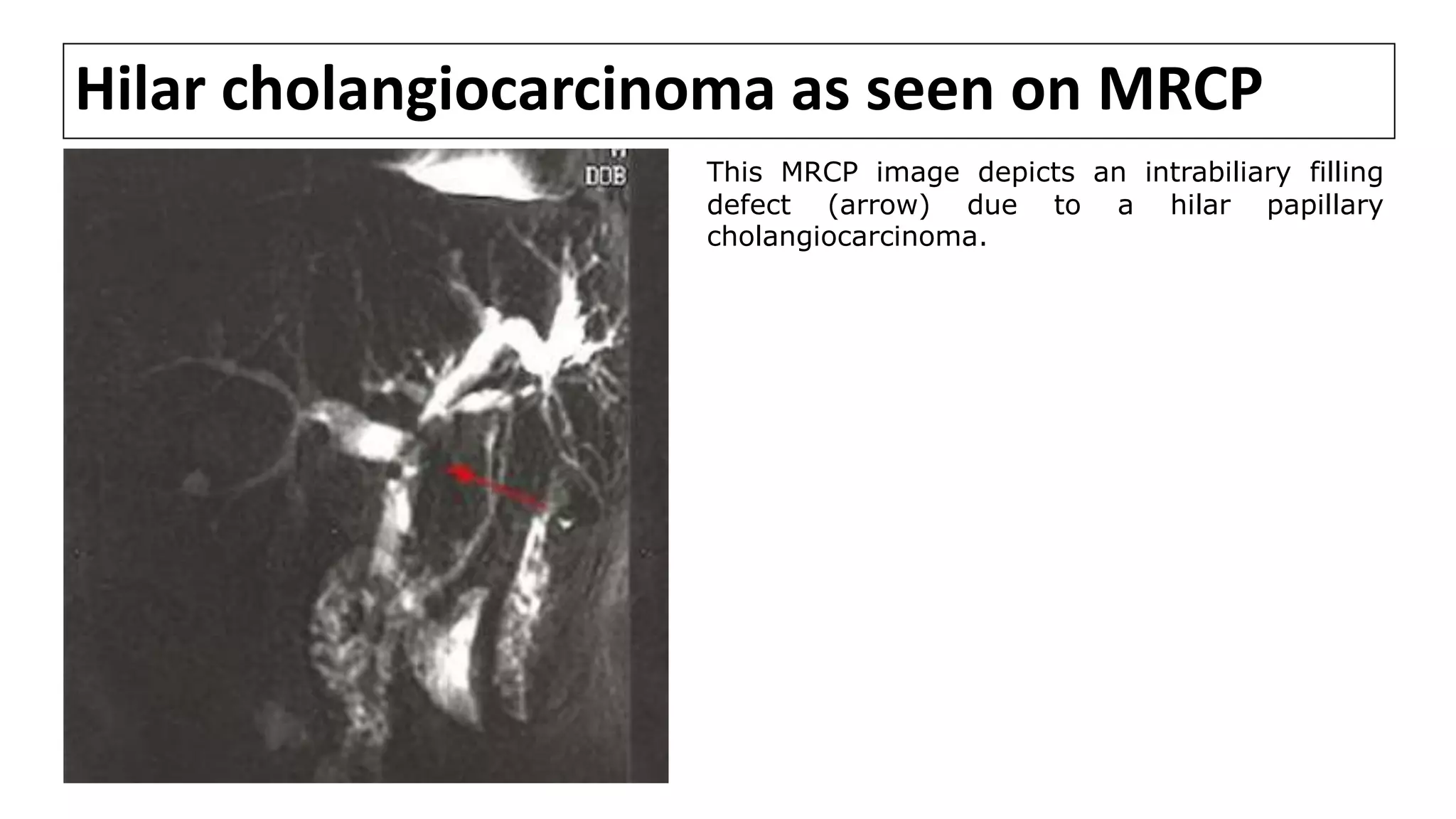

![MRCP

• MRCP provides information about disease extent and potential

resectability that is at least comparable to that obtained using CT,

cholangiography, and angiography [1-7].

• In a series comparing MRCP with ERCP in 40 pts with malignant perihilar

obstruction, both techniques detected 100 % of biliary obstructions

equally. However, MRCP was superior in definition of anatomical extent of

tumor [6].

• However, one of the disadvantages of MRCP is that current technology

does not allow any intervention to be performed, such as stone

extraction, stent insertion, or biopsy.

1. Fulcher AS, Turner MA. HASTE MR cholangiography in the evaluation of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997; 169:1501.

2. Schwartz LH, Coakley FV, Sun Y, et al. Neoplastic pancreaticobiliary duct obstruction: evaluation with breath-hold MR cholangiopancreatography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1998; 170:1491.

3. Zidi SH, Prat F, Le Guen O, et al. Performance characteristics of magnetic resonance cholangiography in the staging of malignant hilar strictures. Gut 2000; 46:103.

4. Lee MG, Park KB, Shin YM, et al. Preoperative evaluation of hilar cholangiocarcinoma with contrast-enhanced three-dimensional fast imaging with steady-state precession magnetic resonance angiography: comparison with intraarterial digital subtraction

angiography. World J Surg 2003; 27:278.

5. Park HS, Lee JM, Choi JY, et al. Preoperative evaluation of bile duct cancer: MRI combined with MR cholangiopancreatography versus MDCT with direct cholangiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 190:396.

6. Yeh TS, Jan YY, Tseng JH, et al. Malignant perihilar biliary obstruction: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatographic findings. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95:432.

7. Rösch T, Meining A, Frühmorgen S, et al. A prospective comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of ERCP, MRCP, CT, and EUS in biliary strictures. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 55:870.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-56-2048.jpg)

![MRI/MRCP

• Cholangiocarcinomas appear as hypointense lesions on T1-weighted

images that are hyperintense on T2-weighted images [1].

• T2-weighted images may also show central hypointensity corresponding

to areas of fibrosis.

• Dynamic images show peripheral enhancement followed by progressive

and concentric filling in of the tumor with contrast material. Pooling of

contrast on delayed images is suggestive of a peripheral CC.

1. Manfredi R, Barbaro B, Masselli G, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 2004; 24:155.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-57-2048.jpg)

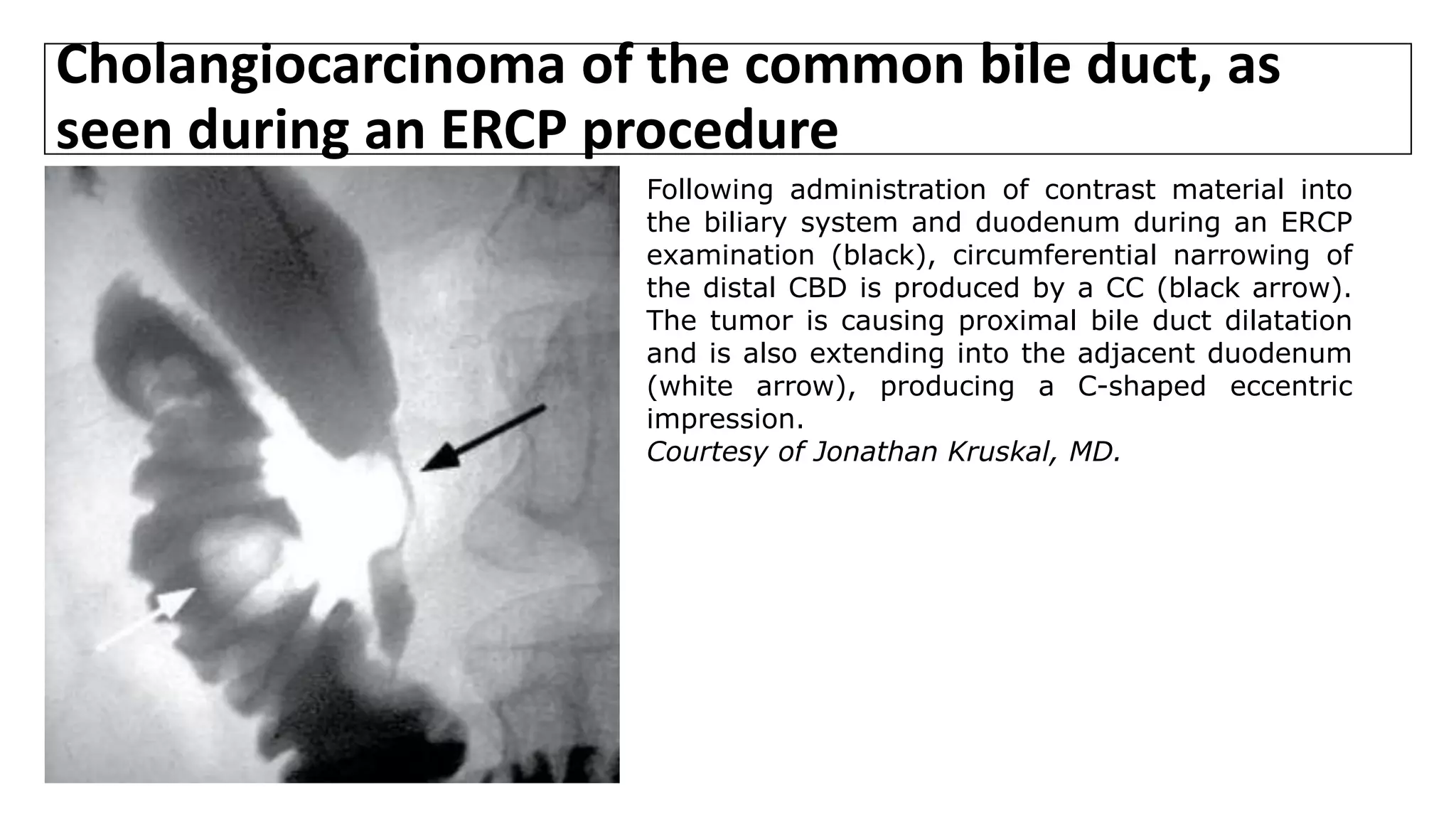

![Cholangiography

• Cholangiography entails an injection of radiographic contrast material to

opacify the bile ducts; it can be performed by ERCP or via a percutaneous

approach (percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram [PTC]).

• Preoperative cholangiography may be indicated either diagnostically or

therapeutically for pts with biliary obstruction.

• MRCP and dynamic CT have largely replaced invasive cholangiography in pts

thought to have a hilar CC in centers with expertise in this technique.

• However, cholangiography may still be indicated if the suspected level of

obstruction is distal, or if preoperative drainage of the biliary tree is

needed. Many surgeons still rely on images from ERCP or PTC rather than

MRCP to determine resectability.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-59-2048.jpg)

![Cholangiography

• ERCP is preferred in pts with PSC since the marked stricturing of the intrahepatic

biliary tree makes a percutaneous approach difficult.

• Conversely, PTC is generally preferred for imaging the more proximal biliary

system if there is complete obstruction of the distal biliary tree.

• In the past, a presumptive DX of sclerosing CC was often made when a focal

stenotic lesion was visualized by cholangiogram in a jaundiced pt.

• However, the inaccuracy of this approach was shown in a series of 98 consecutive

pts in whom a DX other than sclerosing adenocarcinoma was made at surgery in

31 % [1]. There were five papillary CC, 12 GB carcinomas that invaded the bile

duct, five metastatic tumors to the bile duct, and six benign lesions (three

granulomas and three cases of idiopathic benign focal stenosis).

• Although cholangiography is important for visualizing the site and extent of

biliary obstruction, other less invasive and equally accurate studies such as MRCP

should also be utilized.

1. Wetter LA, Ring EJ, Pellegrini CA, Way LW. Differential diagnosis of sclerosing cholangiocarcinomas of the common hepatic duct (Klatskin tumors). Am J Surg 1991; 161:57.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-60-2048.jpg)

![Cholangiography

• If needed, both ERCP and PTC techniques can be used to obtain diagnostic

bile samples or brush cytology.

• Sampling of bile by PTC or ERCP alone will result in positive cytology in

about 30 %of CC [1,2].

• These tests may be useful in the diagnostic evaluation if they are positive,

but a negative test cannot rule out malignant disease.

1. Desa LA, Akosa AB, Lazzara S, et al. Cytodiagnosis in the management of extrahepatic biliary stricture. Gut 1991; 32:1188.

2. Mansfield JC, Griffin SM, Wadehra V, Matthewson K. A prospective evaluation of cytology from biliary strictures. Gut 1997; 40:671.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-61-2048.jpg)

![Cholangiography

• Combining brush cytology with tumor marker assessment may provide

better diagnostic accuracy.

• In a study, the combination of a positive brush cytology or an abnormal CA

19-9 had a SN and SP of 88% and 97%, respectively [1]

• Once instrumentation of the biliary tree has been accomplished, an

endoprosthesis can be placed to provide biliary drainage.

1. Siqueira E, Schoen RE, Silverman W, et al. Detecting cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56:40.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-63-2048.jpg)

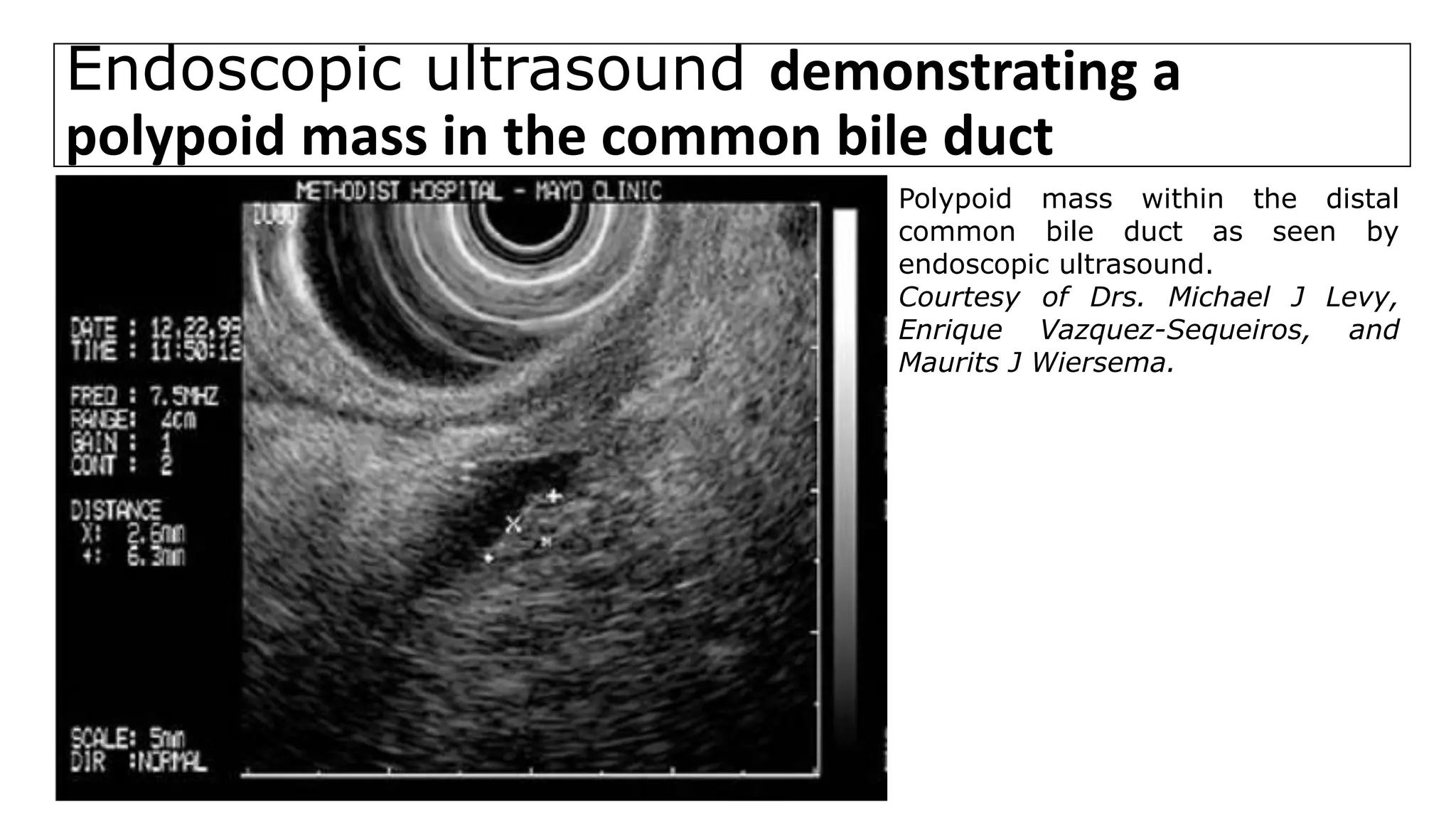

![Endoscopic ultrasound

• For distal bile duct lesions, EUS can visualize the local extent of the

primary tumor and the status of regional lymph nodes.

• EUS-guided fine needle biopsy of tumors and enlarged nodes can also be

performed.

• EUS with fine needle aspiration biopsy has a greater SN for detecting

malignancy in distal tumors than does ERCP with brushings [1]. This

technique also avoids contamination of the biliary tree, which can occur

with ERCP.

1. Abu-Hamda EM, Baron TH. Endoscopic management of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 2004; 24:165.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-64-2048.jpg)

![Endoscopic ultrasound

• One series included 73 pts with either PC(n = 54) or CC (n = 19), all of

whom underwent preoperative EUS, transabdominal ultrasound (TUS), CT

and angiography [1].

• EUS was significantly more SN for the detection of the cancer (96%) than

TUS (81 %), CT (86 %), or angiography (59 %).

• For diagnosing PV invasion, EUS was more SN (95%) and accurate (93%)

than TUS (55% and 67%), CT (65% and 95%), and angiography (75% and 79

%), respectively.

• The role of EUS for imaging and staging proximal bile duct lesions is

uncertain; clinical experience is limited [2].

1. Sugiyama M, Hagi H, Atomi Y, Saito M. Diagnosis of portal venous invasion by pancreatobiliary carcinoma: value of endoscopic ultrasonography. Abdom Imaging 1997; 22:434.

2. Fritscher-Ravens A, Broering DC, Knoefel WT, et al. EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration of suspected hilar cholangiocarcinoma in potentially operable patients with negative brush cytology. Am J Gastroenterol

2004; 99:45.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-65-2048.jpg)

![Intraductal ultrasound

• IDUS can help distinguish benign from malignant strictures based upon

bile duct anatomy and unique sonographic imaging characteristics .

• In addition, IDUS can improve the accuracy of local tumor staging of bile

duct carcinomas.

• IDUS detects early lesions, determines the longitudinal tumor extent, and

identifies tumor extension into adjacent organs and major blood vessels

with a DX accuracy of nearly 100 % [1,2,3,4].

1. Tamada K, Ido K, Ueno N, et al. Assessment of portal vein invasion by bile duct cancer using intraductal ultrasonography. Endoscopy 1995; 27:573.

2. Tamada K, Ueno N, Ichiyama M, et al. Assessment of pancreatic parenchymal invasion by bile duct cancer using intraductal ultrasonography. Endoscopy 1996; 28:492.

3. Kuroiwa M, Tsukamoto Y, Naitoh Y, et al. New technique using intraductal ultrasonography for the diagnosis of bile duct cancer. J Ultrasound Med 1994; 13:189.

4. Tamada K, Ido K, Ueno N, et al. Assessment of the course and variations of the hepatic artery in bile duct cancer by intraductal ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc 1996; 44:249.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-67-2048.jpg)

![Intraductal ultrasound

• In particular, IDUS can accurately identify tumor invasion into the

pancreatic parenchyma [2,3,5], PV [1,3,5,6], and right hepatic artery

[3,4,5,7].

• In contrast to EUS, IDUS is often better able to evaluate the proximal

biliary system and surrounding structures, such as the right hepatic artery,

portal vein, and the hepatoduodenal ligament.

• IDUS may also have limited value in evaluating lymph nodes, and unlike

EUS, IDUS cannot be used to perform fine-needle aspiration.

1. Tamada K, Ido K, Ueno N, et al. Assessment of portal vein invasion by bile duct cancer using intraductal ultrasonography. Endoscopy 1995; 27:573.

2. Tamada K, Ueno N, Ichiyama M, et al. Assessment of pancreatic parenchymal invasion by bile duct cancer using intraductal ultrasonography. Endoscopy 1996; 28:492.

3. Kuroiwa M, Tsukamoto Y, Naitoh Y, et al. New technique using intraductal ultrasonography for the diagnosis of bile duct cancer. J Ultrasound Med 1994; 13:189.

4. Tamada K, Ido K, Ueno N, et al. Assessment of the course and variations of the hepatic artery in bile duct cancer by intraductal ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc 1996; 44:249.

5. Tamada K, Ido K, Ueno N, et al. Preoperative staging of extrahepatic bile duct cancer with intraductal ultrasonography. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90:239.

6. Yasuda K, Mukai H, Nakajima M, Kawai K. Clinical application of ultrasonic probes in the biliary and pancreatic duct. Endoscopy 1992; 24 Suppl 1:370.

7. Tamada K, Ido K, Ueno N, et al. Assessment of hepatic artery invasion by bile duct cancer using intraductal ultrasonography. Endoscopy 1995; 27:579.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-68-2048.jpg)

![PET scan

• PET scan permits visualization of CC because of the high glucose uptake of bile

duct epithelium. PET scans can detect nodular CC as small as 1 cm but is less

helpful for infiltrating tumors [1,2,3].

• Perhaps more important is the role of PET in identifying occult metastases [2-4].

• In one series, PET led to a change in surgical MX in 11 of 36 pts evaluated for CC

because of detection of unsuspected metastases [3].

• Another role of PET is in screening pts with PSC for the presence of CC [6,7,8].

• In one small study PET scans were performed in 9 pts with PSC, 6 with PSC and

known CC, and 5 controls [6]. PET scan correctly identified "hot spots" in all 6 pts

with CC and none in the other groups.

• However, the possibility of acute cholangitis causing a false-positive study has

to be considered in pts with PSC [3]. The place of PET scanning in the evaluation

of these pts remains unresolved.

References are at the end of slides](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-69-2048.jpg)

![Establishing a preoperative tissue diagnosis

Tissue diagnosis is most important in the following circumstances [1]:

• Strictures of clinically indeterminate origin (eg, in pts with a HX of biliary

tract surgery, bile duct stones, or PSC)

• A situation where the physician or pt would be reluctant to proceed with

surgery without a tissue diagnosis, or if the patient's or family's acceptance

and adjustment to the diagnosis would be facilitated by having a definitive

diagnosis.

• Prior to chemotherapy or radiation therapy, particularly if the pt will be

enrolling on a therapeutic clinical trial,

1. Pelsang RE, Johlin FC. A percutaneous biopsy technique for patients with suspected biliary or pancreatic cancer without a radiographic mass. Abdom Imaging 1997; 22:307](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-71-2048.jpg)

![Staging laparoscopy

• Despite the enhanced diagnostic capability of newer radiologic studies such

as MRCP and dynamic CT, unless there is clear evidence of metastatic

disease, true resectability can be determined only by operative evaluation.

• Laparoscopy can identify the majority of pts with unresectable hilar and

distal cholangiocarcinoma, thereby reducing the number of unnecessary

laparotomies [1,2].

• However, true resectability can often be determined only after a complete

abdominal exploration [3].

1. Weber SM, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, et al. Staging laparoscopy in patients with extrahepatic biliary carcinoma. Analysis of 100 patients. Ann Surg 2002; 235:392.

2. Callery MP, Strasberg SM, Doherty GM, et al. Staging laparoscopy with laparoscopic ultrasonography: optimizing resectability in hepatobiliary and pancreatic malignancy. J Am Coll Surg 1997; 185:33.

3. Su CH, Tsay SH, Wu CC, et al. Factors influencing postoperative morbidity, mortality, and survival after resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 1996; 223:384.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-72-2048.jpg)

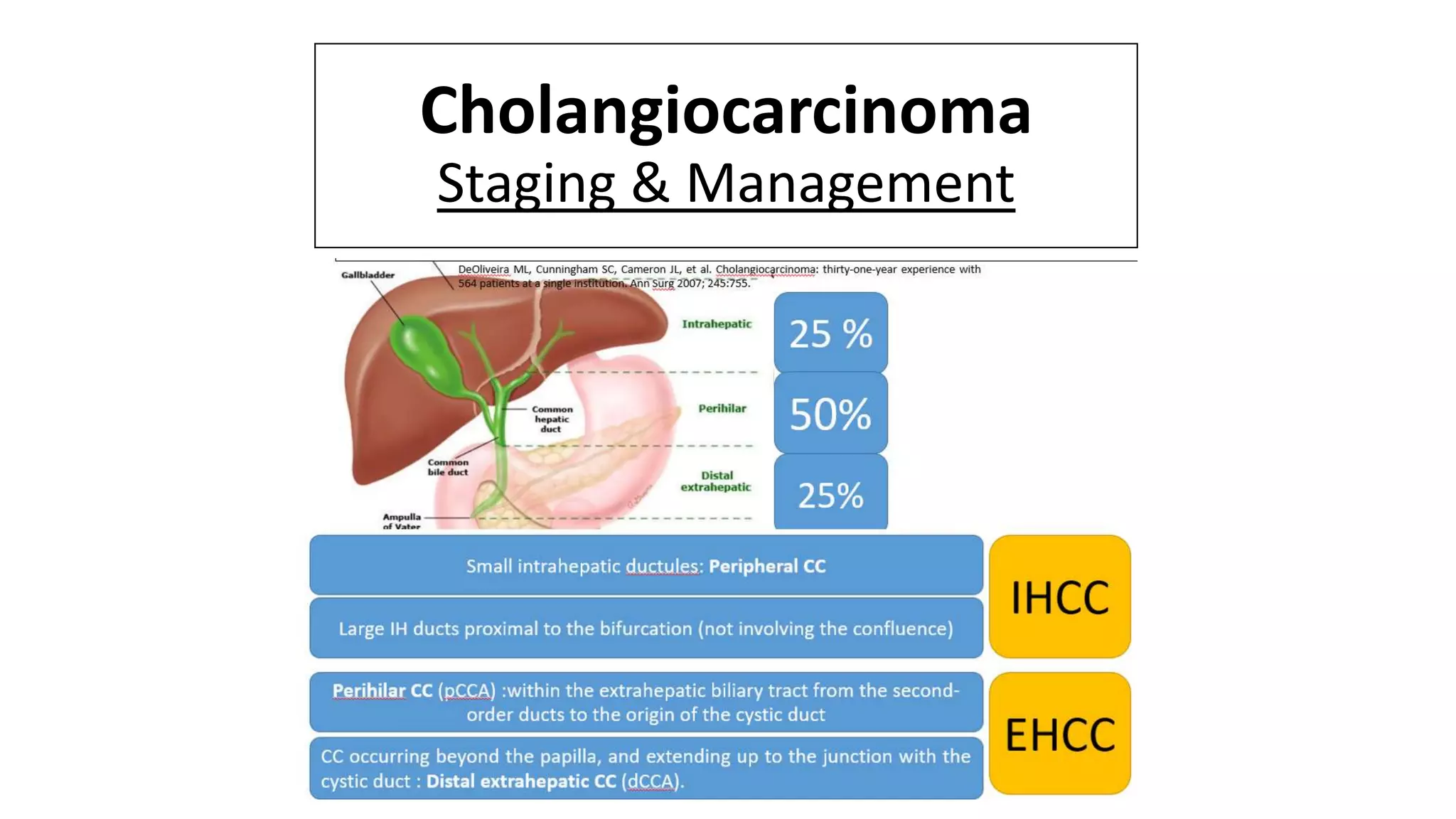

![TNM Pathological Classification of IHCC;7TH ED[1]

M0: No distant metastasis; M1: distant metastasis; N0: no regional LN metastasis; N1, regional LN metastases;

• T1, solitary tumor without vascular invasion;

• T2a, solitary tumor with vascular invasion;

• T2b, multiple tumors with vascular invasion;

• T3, tumor perforating the visceral peritoneum or involving the local extrahepatic structures by direct invasion;

• T4, tumor(s) with direct invasion of adjacent organs other than GB or with perforation of visceral peritoneum.

5 yr Survival %

[2]

58.8

38.8

39.7

18.4

1. Data from Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C, editors. International Union against Cancer (UICC): TNM classification of malignant tumors, 7th ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

2. From: Spolverato G, Bagante F, Weiss M, et al. Comparative performances of the 7th and the 8th editions of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging systems for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Surg

Oncol 2017; 115:696.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-75-2048.jpg)

![TNM Pathological Classification of Perihilar CC;7TH ED[1]

1. Data from Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C, editors. International Union against Cancer (UICC): TNM classification of malignant tumors, 7th ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

M0, No distant metastasis;

M1, distant metastasis;

N1, regional LN metastasis

(including nodes along the cystic duct, CBD,

hepatic artery, and portal vein);

N2, Metastasis to periaortic, pericaval, superior

mesenteric artery, and/or celiac artery LN;

• T1: Ductal wall

• T2a: Beyond ductal wall

• T2b: Adjacent hepatic parenchyma

• T3: Unilateral PV or hepatic artery branches

• T4; Main portal vein or branches bilaterally](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-76-2048.jpg)

![• However, long-term studies have indicated that the resectability and

prognosis of HCC are closely related to portal vein involvement and liver

lobe atrophy, largely because of the complex local anatomical structure of

HCC and the aggressive nature of the tumor cells.[1,2]

• Therefore, Burke et al.[3] and Jarnagin et al.[4]further proposed use of T-

stage and modified T-stage, respectively, for clinical subtyping of HCC.

1. Hadjis NS, Blenkharn JI, Alexander N, et al. Outcome of radical surgery in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery 1990; 107: 597–604.

2. Klempnauer J, Ridder GJ, von Wasielewski R, et al. Resectional surgery of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a multivariate analysis of prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 947–954.

3. Pichlmayr R, Weimann A, Klempnauer J, et al. Surgical treatment in proximal bile duct cancer. A single-center experience. Ann Surg 1996; 224: 628–638.

4. Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Kondo S, et al. Aggressive preoperative management and extended surgery for hilar cholangiocar cinoma: Nagoya experience. J Hep Bil Panc Surg 2000; 7: 155–162.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-78-2048.jpg)

![TNM Pathological Classification of Distal CC;7TH ED[1]

M0, No distant metastasis; M1, distant metastasis; N1, regional;

• T1: Ductal wall;

• T2a: Beyond ductal wall;

• T3: Adjacent organs;

• T4: Celiac axis or superior mesenteric artery.

1.Data from Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C, editors. International Union against Cancer (UICC): TNM classification of malignant tumors, 7th ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-81-2048.jpg)

![SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

• In general, CC have an extremely poor prognosis, with an average 5-yr

survival rate of 5-10 %.

• Distal CC have the highest resectability rates while proximal (both

intrahepatic and perihilar) tumors have the lowest.

• In one large series, the resectability rates for distal, intrahepatic, and

perihilar lesions were 91, 60, and 56 %, respectively [1].

• Even in pts who undergo potentially curative resection, tumor-free

margins can be obtained in only 20-40 % of proximal and 50 % of distal

tumors [2].

1. Nakeeb A, Pitt HA, Sohn TA, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors. Ann Surg 1996; 224:463.

2. Burke EC, Jarnagin WR, Hochwald SN, et al. Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: patterns of spread, the importance of hepatic resection for curative operation, and a presurgical clinical staging system. Ann Surg 1998;

228:385.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-88-2048.jpg)

![Criteria for resectability

The traditional guidelines for resectability of CC in the US include [1,2]:

• Absence of retropancreatic and paraceliac nodal metastases or distant

liver metastases

• Absence of invasion of the PV or main HA(although some centers support

en bloc resection with vascular reconstruction [3,4])

• Absence of extrahepatic adjacent organ invasion

• Absence of disseminated disease

1. Tsao JI, Nimura Y, Kamiya J, et al. Management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: comparison of an American and a Japanese experience. Ann Surg 2000; 232:166.

2. Rajagopalan V, Daines WP, Grossbard ML, Kozuch P. Gallbladder and biliary tract carcinoma: A comprehensive update, Part 1. Oncology (Williston Park) 2004; 18:889.

3. Ebata T, Nagino M, Kamiya J, et al. Hepatectomy with portal vein resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: audit of 52 consecutive cases. Ann Surg 2003; 238:720.

4. Hemming AW, Reed AI, Fujita S, et al. Surgical management of hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2005; 241:693.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-89-2048.jpg)

![Additional Criteria for resectability

• Additional criteria are specific to tumor location.

For instance, radiographic criteria that suggest local unresectability of perihilar

tumors include

Bilateral hepatic duct involvement up to secondary radicles bilaterally,

Encasement or occlusion of the main PV proximal to its bifurcation,

Atrophy of one liver lobe with encasement of the contralateral PV branch,

Atrophy of one liver lobe with contralateral secondary biliary radicle

involvement, or

Involvement of bilateral hepatic arteries [1,2].

However, as a general rule, true resectability is ultimately determined at surgery,

particularly with perihilar tumors [3].

1. Burke EC, Jarnagin WR, Hochwald SN, et al. Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: patterns of spread, the importance of hepatic resection for curative operation, and a presurgical clinical staging system. Ann Surg 1998;

228:385.

2. Chamberlain RS, Blumgart LH. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: a review and commentary. Ann Surg Oncol 2000; 7:55.

3. Su CH, Tsay SH, Wu CC, et al. Factors influencing postoperative morbidity, mortality, and survival after resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 1996; 223:384.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-90-2048.jpg)

![Surgical Therapy: Intrahepatic CC

• In general, IHCC are large tumors at the time of DX and pts need major liver

resections.

• Presence of LN metastasis is a/with worse outcomes.[1]

• Following surgical resection with biopsy-proven negative margins, the 1-yr

survival and 5-yr survival are 72.4% and 30.4%, respectively.[2]

• The most recent retrospective analysis of 535 pts with surgically resected

IHCC has demonstrated that overall survival decreased over time from 39% at

3 yrs to 16% at 8 yrs.[1]

1. Spolverato G, et al: Conditional probability of long-term survival after liver resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multiinstitutional analysis of 535 patients. JAMA Surg 2015.

2. Jonas S, et al: Extended liver resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A comparison of the prognostic accuracy of the fifth and sixth editions of the TNM classification. Ann Surg 249:303–309, 2009.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-91-2048.jpg)

![Prognostic Factors A/with Unfavorable Outcome After Surgical

Treatment of IHCC[1]

1. KONSTANTINOS N. LAZARIDIS and GREGORY J. GORES. Cholangiocarcinoma. GASTROENTEROLOGY 2005;128:1655–1667

Mucin 1, cell surface associated (MUC1) or polymorphic epithelial mucin (PEM) is a mucin encoded by the MUC1 gene in

humans. MUC1 is a glycoprotein that line the apical surface of epithelial cells in the lungs, stomach, intestines, eyes and

several other organs. Mucins protect the body from infection by pathogen binding to oligosaccharides in the extracellular

domain, preventing the pathogen from reaching the cell surface. Overexpression of MUC1 seems to promoting tumor

invasion and is also associated with colon, breast, ovarian, lung and pancretic cancers.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-92-2048.jpg)

![Surgical therapy for Perihilar CC

• In general, pts with resectable perihilar CCA require partial hepatic

resection to have tumor-free margins.

• Pts with tumor-free margins have a 20-40% 5-yr survival rate.[1,2]

• Other independent prognostic factors for long-term survival include LN status

and differentiation grade of the tumor.[3]

• Therefore, the primary aim of surgical resection is biopsy-proven negative

margins and local LN resection.

1. Jarnagin WR, et al: Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 234:507–517,discussion 517–519, 2001.

2. Rea DJ, et al: Major hepatic resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of 46 patients. Arch Surg 139:514–523, discussion 523–525, 2004.

3. Kloek JJ, et al: Surgery for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: predictors of survival. HPB (Oxford) 10:190–195, 2008.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-93-2048.jpg)

![Surgical therapy for Perihilar CC

• In one study, the survival of pts with node-negative CCA was higher in pts

with >seven LN harvested.[1]

• Furthermore, R1 resections (i.e., positive resection margins) had better

survival than unresected pts.[1]

• Notably, perihilar CCA involving the biliary confluence almost always engages

the main caudate duct and demands caudate lobe removal.

1. Rocha FG, et al: Hilar cholangiocarcinoma: the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2009.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-94-2048.jpg)

![Surgical therapy : Distal cholangiocarcinoma

• Distal lesions are usually RX with pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple

procedure).

• Five-yr survival rates range from 23-50% [1-8] but are as high as 62% in

selected pts who undergo complete resection of a node-negative tumor [6].

• However, cure rates may not actually be as high as these reports suggest

since not all series distinguished distal CC from carcinoma of AOV, a

disease that has a significantly higher cure rate. Both diseases (as well as

some cases of PC) are often analyzed together as "periampullary" tumors.

• LN involvement and depth of tumor invasion are important prognostic

indicators [9,10].

References are at the end of slides](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-95-2048.jpg)

![Preoperative biliary decompression(PBD)

• Whether PBD using an endoscopically or percutaneously placed stent

should be carried out in pts who present with obstructive jaundice is

controversial [1,2]. The following issues inform the debate.

• In general, it is preferable to avoid stents, if possible. The ability to carry

out the precise imaging that is required to assess unresectability is limited

once a stent is in place. Furthermore, many surgeons find the presence of

any biliary stent a hindrance to determining the proximal tumor extent

intraoperatively.

• On the other hand, cholestasis, liver dysfunction, and biliary cirrhosis

develop rapidly with unrelieved obstruction. The extent of liver dysfunction

is one of the main factors that ↑ postoperative morbidity and mortality

following surgical resection [3].

1. Laurent A, Tayar C, Cherqui D. Cholangiocarcinoma: preoperative biliary drainage (Con). HPB (Oxford) 2008; 10:126.

2. Nimura Y. Preoperative biliary drainage before resection for cholangiocarcinoma (Pro). HPB (Oxford) 2008; 10:130.

3. Su CH, Tsay SH, Wu CC, et al. Factors influencing postoperative morbidity, mortality, and survival after resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg 1996; 223:384.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-96-2048.jpg)

![Preoperative biliary decompression

• Although experimental studies in jaundiced animals suggest that PBD

improves surgical outcomes, clinical studies report variable benefit from

PBD in terms of morbidity and mortality.

• Much of the data are derived from jaundiced pts with pancreatic cancer.

• Several such series report deleterious effects of drainage prior to

pancreaticoduodenectomy, including an ↑ risk of cholangitis and longer

postoperative hospital stay [1-5].

1. Heslin MJ, Brooks AD, Hochwald SN, et al. A preoperative biliary stent is associated with increased complications after pancreatoduodenectomy. Arch Surg 1998; 133:149.

2. Motte S, Deviere J, Dumonceau JM, et al. Risk factors for septicemia following endoscopic biliary stenting. Gastroenterology 1991; 101:1374.

3. Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al. Do preoperative biliary stents increase postpancreaticoduodenectomy complications? J Gastrointest Surg 2000; 4:258.

4. Pitt HA, Gomes AS, Lois JF, et al. Does preoperative percutaneous biliary drainage reduce operative risk or increase hospital cost? Ann Surg 1985; 201:545.

5. Lai EC, Mok FP, Fan ST, et al. Preoperative endoscopic drainage for malignant obstructive jaundice. Br J Surg 1994; 81:1195.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-97-2048.jpg)

![Preoperative biliary decompression

• Only one study has examined the impact of major liver resection in

jaundiced pts [1].

• 20 consecutive pts with obstructive jaundice (14 CC, 5 GB cancers, one HCC)

who were to undergo major liver resection without preoperative biliary

drainage were matched (for age, tumor size, type of liver resection, and

vascular occlusion) with 27 nonjaundiced pts undergoing liver resection for a

variety of reasons. Although there were no significant differences in

mortality (5 vs 0 %) or the incidence of postoperative liver failure (5 vs 0 %),

postoperative morbidity rates (mainly resulting from subphrenic collections

and bile leaks) were significantly higher in the jaundiced pts (50 Vs 15 %).

• These data support a potential benefit for preoperative drainage.

1. Cherqui D, Benoist S, Malassagne B, et al. Major liver resection for carcinoma in jaundiced patients without preoperative biliary drainage. Arch Surg 2000; 135:302.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-98-2048.jpg)

![Preoperative biliary decompression

However, a meta-analysis of 11 studies addressing the benefit of PBD in

jaundiced pts with hilar CC came to the following conclusions [1]:

• There was no difference in death rate or length of postoperative stay with

and without PBD.

• Overall postoperative complications rates and infectious complication

rates were significantly adversely affected by PBD as compared to surgery

without PBD.

• In the absence of evidence for a clinical benefit, preoperative biliary

decompression in jaundiced pts with hilar CC planned for surgery should

not be routinely performed. Randomized trials with large sample size and

optimal biliary drainage techniques are needed.

1. Liu F, Li Y, Wei Y, Li B. Preoperative biliary drainage before resection for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: whether or not? A systematic review. Dig Dis Sci 2011; 56:663.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-99-2048.jpg)

![Preoperative biliary decompression

The best method (endoscopic versus percutaneous transhepatic) by which to

perform preoperative biliary drainage is also debated [1].

• These unresolved issues as to the benefit of PBD and the best means of achieving

biliary decompression has led to differing approaches. Many surgeons proceed

directly to laparotomy without preoperative biliary drainage [2,3].

• As a practical issue, endoscopic stents are often placed to alleviate jaundice while

these issues are being settled. If an endoscopic stent cannot be placed for

whatever reason, a percutaneous approach is generally tried.

• One approach is to perform nonoperative biliary drainage selectively in pts with

a serum bilirubin level>10 mg/dL, deferring definitive operative intervention

until bilirubin levels are under 3 mg/dL. However, if stent placement is planned,

high quality imaging necessary to assess unresectability (CT, MRI, ERCP, MRCP)

should be performed beforehand.

1. Kloek JJ, van der Gaag NA, Aziz Y, et al. Endoscopic and percutaneous preoperative biliary drainage in patients with suspected hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg 2010; 14:119.

2. Cherqui D, Benoist S, Malassagne B, et al. Major liver resection for carcinoma in jaundiced patients without preoperative biliary drainage. Arch Surg 2000; 135:302.

3. Hodul P, Creech S, Pickleman J, Aranha GV. The effect of preoperative biliary stenting on postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg 2003; 186:420.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-100-2048.jpg)

![Preoperative portal vein embolization

• Because the achievement of histologically negative resection margins is so

critical to outcome, preoperative PVE has been used in an attempt to

increase the limits of safe resection [1-6].

• The intent of PVE is to induce lobar hypertrophy in pts who have a

predicted postoperative liver remnant volume of <25 %. By allowing a

larger resection volume to be carried out safely, PVE may permit a margin-

negative resection in pts who otherwise would be considered unresectable

because of concerns about insufficient postoperative residual liver volume.

• A resection of >75% of the total liver volume in a healthy liver and >65% of

the total liver volume in a compromised liver (eg, due to cirrhosis or

fibrosis) is an indication of portal vein embolization (PVE).[7]

1. Madoff DC, Hicks ME, Abdalla EK, et al. Portal vein embolization with polyvinyl alcohol particles and coils in preparation for major liver resection for hepatobiliary malignancy: safety and effectiveness--study in 26 patients. Radiology 2003; 227:251.

2. Hemming AW, Reed AI, Howard RJ, et al. Preoperative portal vein embolization for extended hepatectomy. Ann Surg 2003; 237:686.

3. Abdalla EK, Barnett CC, Doherty D, et al. Extended hepatectomy in patients with hepatobiliary malignancies with and without preoperative portal vein embolization. Arch Surg 2002; 137:675.

4. Nimura Y, Kamiya J, Kondo S, et al. Aggressive preoperative management and extended surgery for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Nagoya experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2000; 7:155.

5. Nagino M, Kamiya J, Nishio H, et al. Two hundred forty consecutive portal vein embolizations before extended hepatectomy for biliary cancer: surgical outcome and long-term follow-up. Ann Surg 2006; 243:364.

6. Di Stefano DR, de Baere T, Denys A, et al. Preoperative percutaneous portal vein embolization: evaluation of adverse events in 188 patients. Radiology 2005; 234:625.

7. van Lienden KP, van den Esschert JW, de Graaf W, et al. Portal vein embolization before liver resection: a systematic review. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36(1):25–34.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-101-2048.jpg)

![Adjuvant therapy: European Society of Medical Oncology

(ESMO)[1]

Guidelines from the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) for

treatment of either intrahepatic or EH CC suggest

• After complete surgical resection: consideration of postoperative

chemoradiotherapy.

• After a noncurative resection: supportive care or palliative CT and/or

radiotherapy

1. Eckel F, Jelic S, ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Biliary cancer: ESMO clinical recommendation for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2009; 20 Suppl 4:46.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-103-2048.jpg)

![Systemic Therapy

• The Advanced Biliary Cancer 2 (ABC-2) study has established the

chemotherapeutic combination of gemcitabine with cisplatin as a practice

standard for advanced CC.[1]

• Pts (n = 410) were randomized to receive combination therapy with

gemcitabine and cisplatin or gemcitabine alone for 6 mnths. Median OS in

pts who received a combination vs gemcitabine alone was 11.7 mnths and

8.1 mnths, respectively .

• Though the benefits of this cytotoxic therapy were modest, It should also be

noted that pts with IHCC responded better than pts with perihilar CC.

1. Valle J, et al: Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med 362:1273–1281, 2010.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-105-2048.jpg)

![Systemic Therapy with targeted therapy

• There is a growing number of clinical trials with targeted therapy alone or in

combination with traditional CT for CC.

• A randomized, Phase III trial with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin with or without

erlotinib demonstrated minimally significant improvement in a median

progression-free survival with CT plus targeted therapy (5.9 mnths) Vs CT alone (3

mnths).

• A study that randomized 150 pts to a combination of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin

with or without the anti-EGFR antibody cetuximab showed minimal benefits of

adding targeted therapy. [1]

• Results of the study where pts were randomized between a gemcitabine CT

backbone with or without sorafenib demonstrated absence in improvement in a

disease control or overall survival, but rather a higher toxicity of the

combination.[2]

1. Malka D, et al: Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin with or without cetuximab in advanced biliary-tract cancer (BINGO): a randomised, open-label, non-comparative phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 15:819–828, 2014.

2. Moehler M, et al: Gemcitabine plus sorafenib versus gemcitabine alone in advanced biliary tract cancer: a double-blind placebocontrolled multicentre phase II AIO study with biomarker and serum programme. Eur J

Cancer 50:3125–3135, 2014.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-106-2048.jpg)

![Stenting

• Placement of a stent is generally preferred for long-term palliation since it

is a/with similar rates of successful palliation and survival but less morbidity

compared to the surgical approach [1-8].

• Nevertheless, successful endoscopic deployment of a stent (or multiple

stents as needed to span the malignant stricture) is possible in 70-100% of

pts.

• Among the major issues are the optimal approach to stent placement,

extent of decompression that is necessary to restore sufficient bile flow

while avoiding the risk of bacterial cholangitis, and the use of plastic or

metal (and bare versus covered) stents.

1. Washburn WK, Lewis WD, Jenkins RL. Aggressive surgical resection for cholangiocarcinoma. Arch Surg 1995; 130:270.

2. Pichlmayr R, Weimann A, Klempnauer J, et al. Surgical treatment in proximal bile duct cancer. A single-center experience. Ann Surg 1996; 224:628.

3. Benjamin IS. Surgical possibilities for bile duct cancer: standard surgical treatment. Ann Oncol 1999; 10 Suppl 4:239.

4. Smith AC, Dowsett JF, Russell RC, et al. Randomised trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgical bypass in malignant low bileduct obstruction. Lancet 1994; 344:1655.

5. Shepherd HA, Royle G, Ross AP, et al. Endoscopic biliary endoprosthesis in the palliation of malignant obstruction of the distal common bile duct: a randomized trial. Br J Surg 1988; 75:1166.

6. Lai EC, Chu KM, Lo CY, et al. Choice of palliation for malignant hilar biliary obstruction. Am J Surg 1992; 163:208.

7. Andersen JR, Sørensen SM, Kruse A, et al. Randomised trial of endoscopic endoprosthesis versus operative bypass in malignant obstructive jaundice. Gut 1989; 30:1132.

8. Prat F, Chapat O, Ducot B, et al. Predictive factors for survival of patients with inoperable malignant distal biliary strictures: a practical management guideline. Gut 1998; 42:76.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cholangiocarcinoma-180815121132/75/Cholangiocarcinoma-111-2048.jpg)

![Percutaneous versus endoscopic approach

• Retrospective series and at least two trials conducted in pts with

obstructive jaundice from a malignant hilar obstruction suggest that

successful palliation of jaundice is more likely, and rates of early

cholangitis may be lower with percutaneous as compared to endoscopic

approach to biliary drainage [1,2,3].

• However, other complications may be more frequent (eg, bile leaks and

bleeding), potentially increasing morbidity and mortality [2,4].

• Furthermore, percutaneous stents are usually left to open drainage

external to the body, at least initially, and this is often inconvenient to the

pt. As a result, in most institutions, an initial endoscopic attempt at

drainage is usually preferred, if possible.

1. Saluja SS, Gulati M, Garg PK, et al. Endoscopic or percutaneous biliary drainage for gallbladder cancer: a randomized trial and quality of life assessment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6:944.

2. Piñol V, Castells A, Bordas JM, et al. Percutaneous self-expanding metal stents versus endoscopic polyethylene endoprostheses for treating malignant biliary obstruction: randomized clinical trial. Radiology 2002; 225:27.