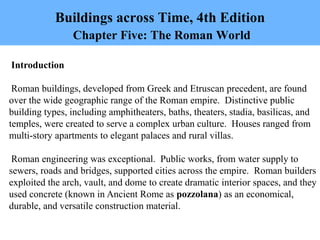

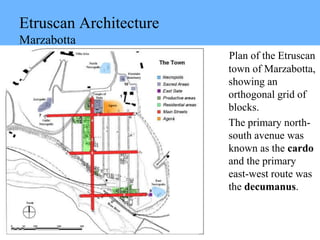

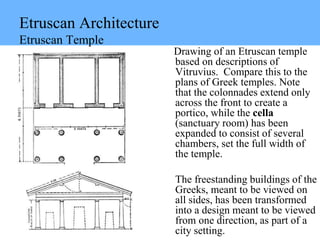

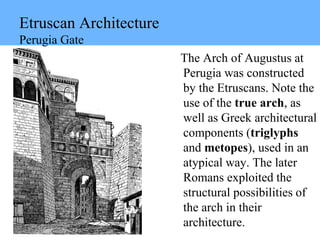

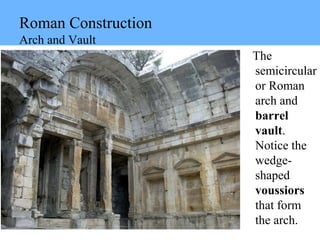

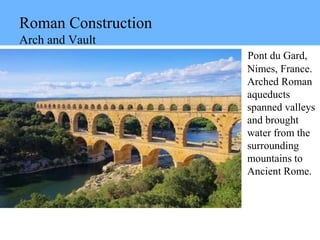

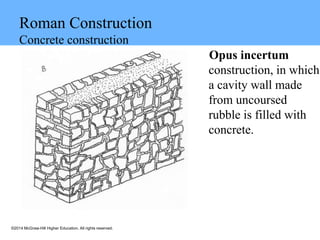

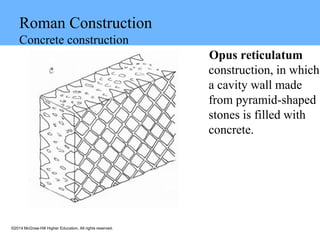

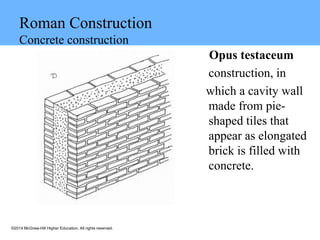

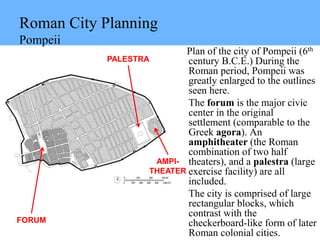

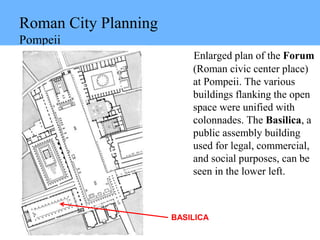

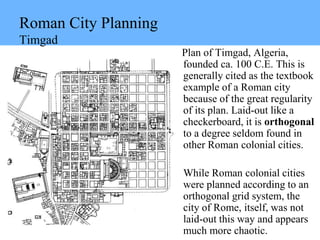

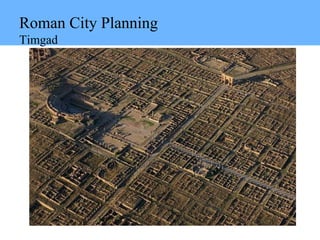

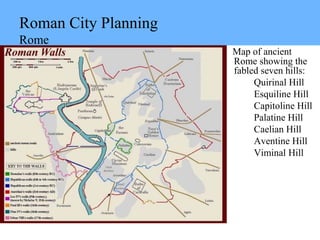

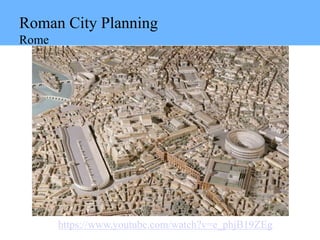

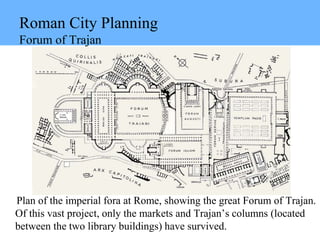

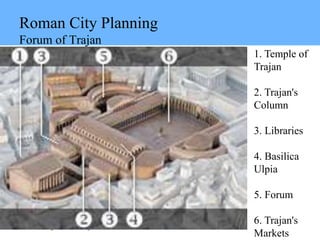

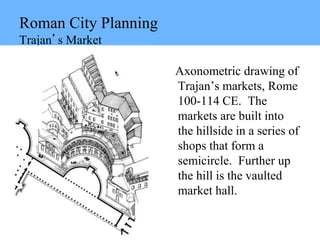

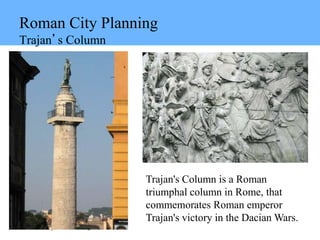

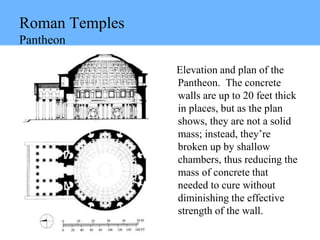

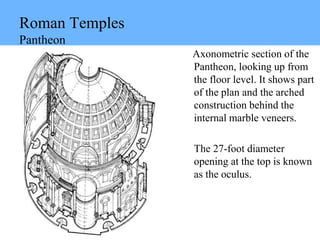

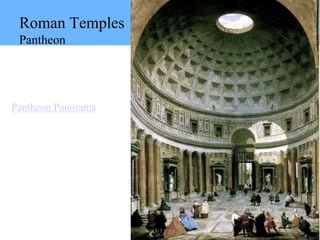

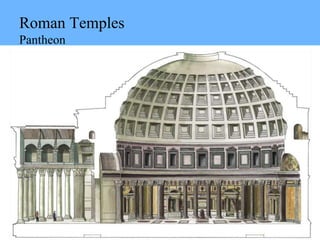

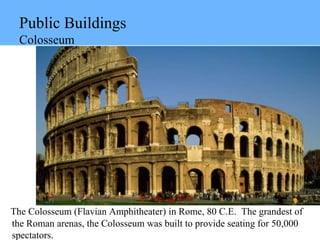

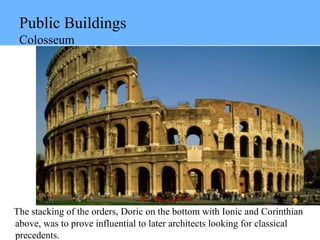

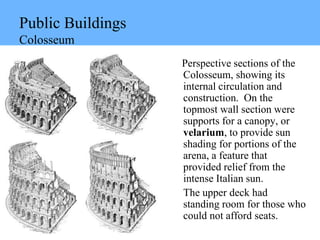

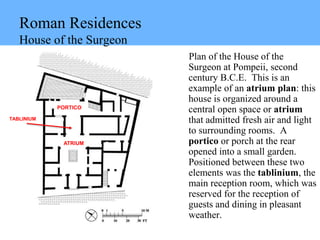

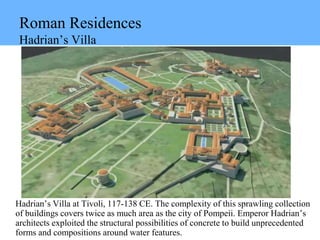

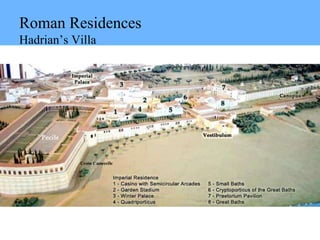

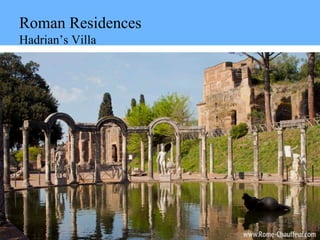

Roman buildings developed from Greek and Etruscan precedents and were found across the Roman Empire. Distinctive public building types included amphitheaters, baths, theaters, and basilicas which served urban culture. Houses ranged from apartments to palaces and villas. Roman engineering created dramatic interior spaces through arched vaults and domes, and used durable concrete. Cities followed an orthogonal grid plan with civic buildings like forums and temples.