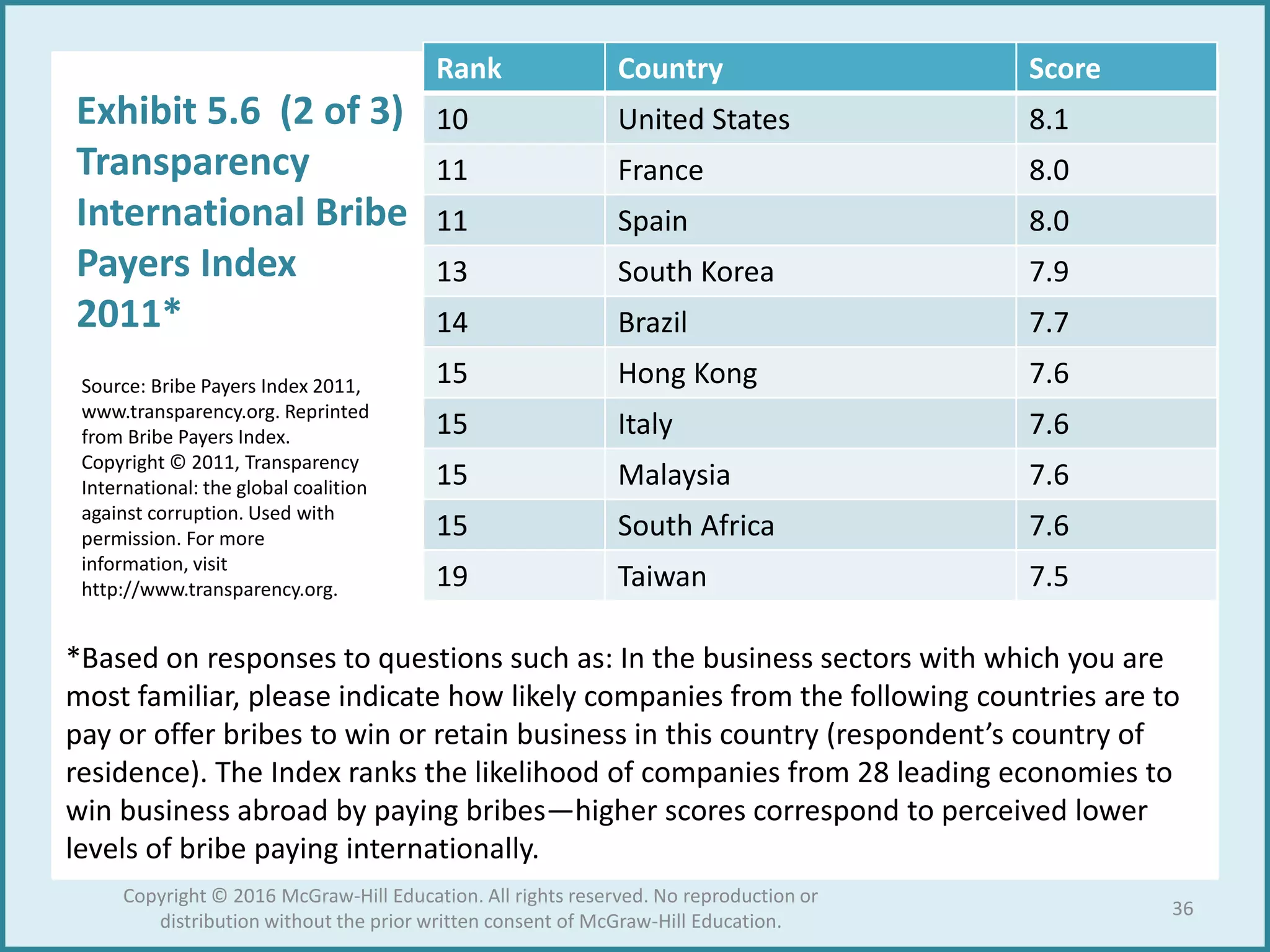

This document discusses cultural differences that impact business practices globally. It covers how management styles, communication styles, views of time, gender biases, and business ethics can vary significantly between cultures. Adaptation to different cultural norms is identified as key for international business success. Specific differences highlighted include decision making and objectives in management, high versus low context communication, monochronic versus polychronic time, and varying levels of corruption. Understanding these cultural factors is important for operating effectively across borders.

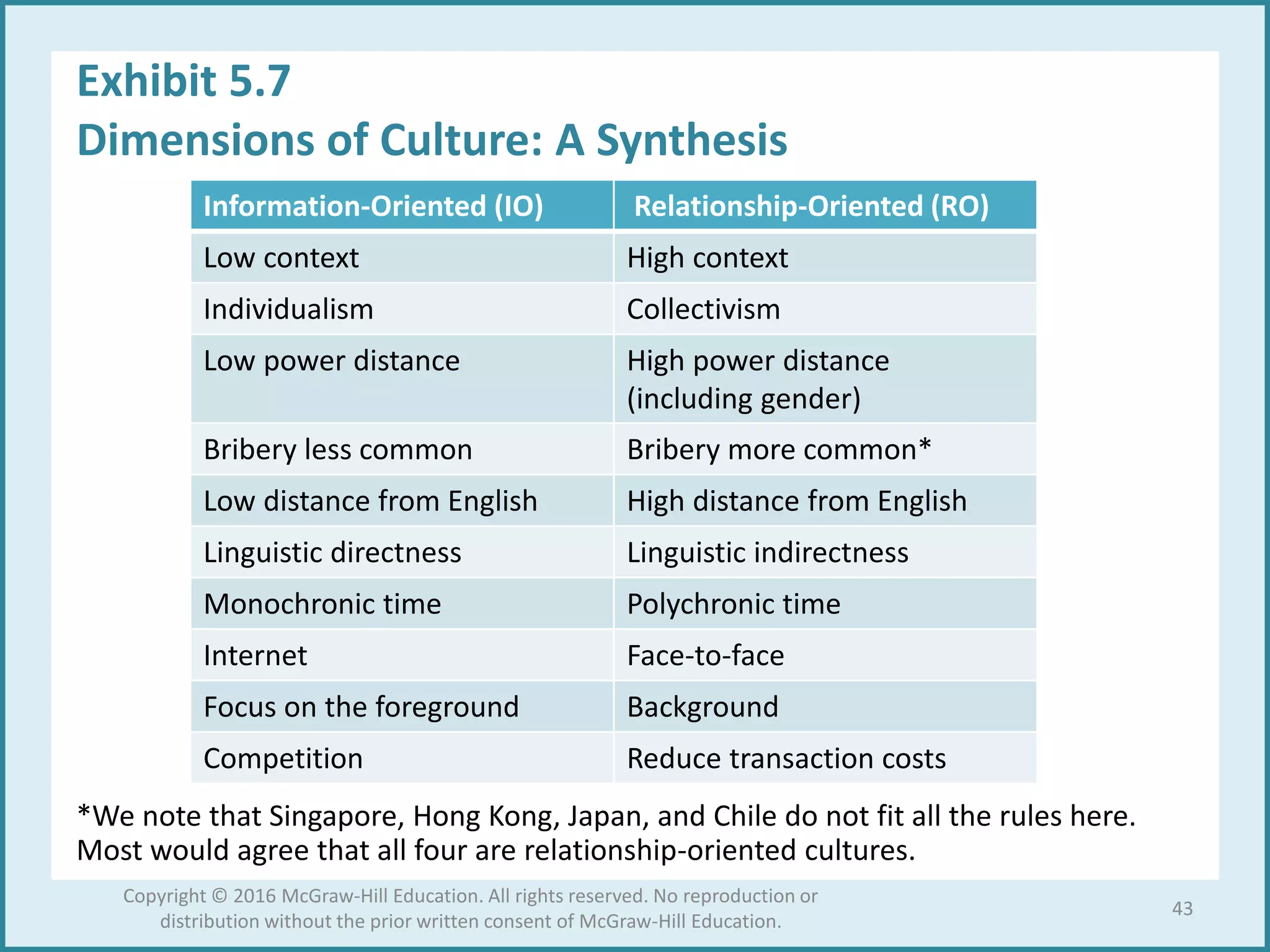

![Overall

Pace

Country Walking 60

Feet

Postal

Service

Public

Clocks

1 Switzerland 3 2 1

2 Ireland 1 3 11

3 Germany 5 1 8

4 Japan 7 4 6

5 Italy 10 12 2

6 England 4 9 13

7 Sweden 13 5 7

8 Austria 23 8 9

9 Netherlands 2 14 25

10 Hong Kong 14 6 14

11 France 8 18 10

Exhibit 5.3

(1 of 3)

Speed Is

Relative

Rank of 31 countries for overall pace of life [combination of three measures: (1) minutes

downtown pedestrians take to walk 60 feet, (2) minutes it takes a postal clerk to

complete a stamp-purchase transaction, and (3) accuracy in minutes of public clocks].

Source: Robert

Levine, “The Pace

of Life in 31

Countries,”

American

Demographics,

November 1997.

Reprinted with

permission of

Robert Levine.

20

Copyright © 2016 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or

distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill Education.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pptch05kp-170221211928/75/Chapter-5-PowerPoint-20-2048.jpg)

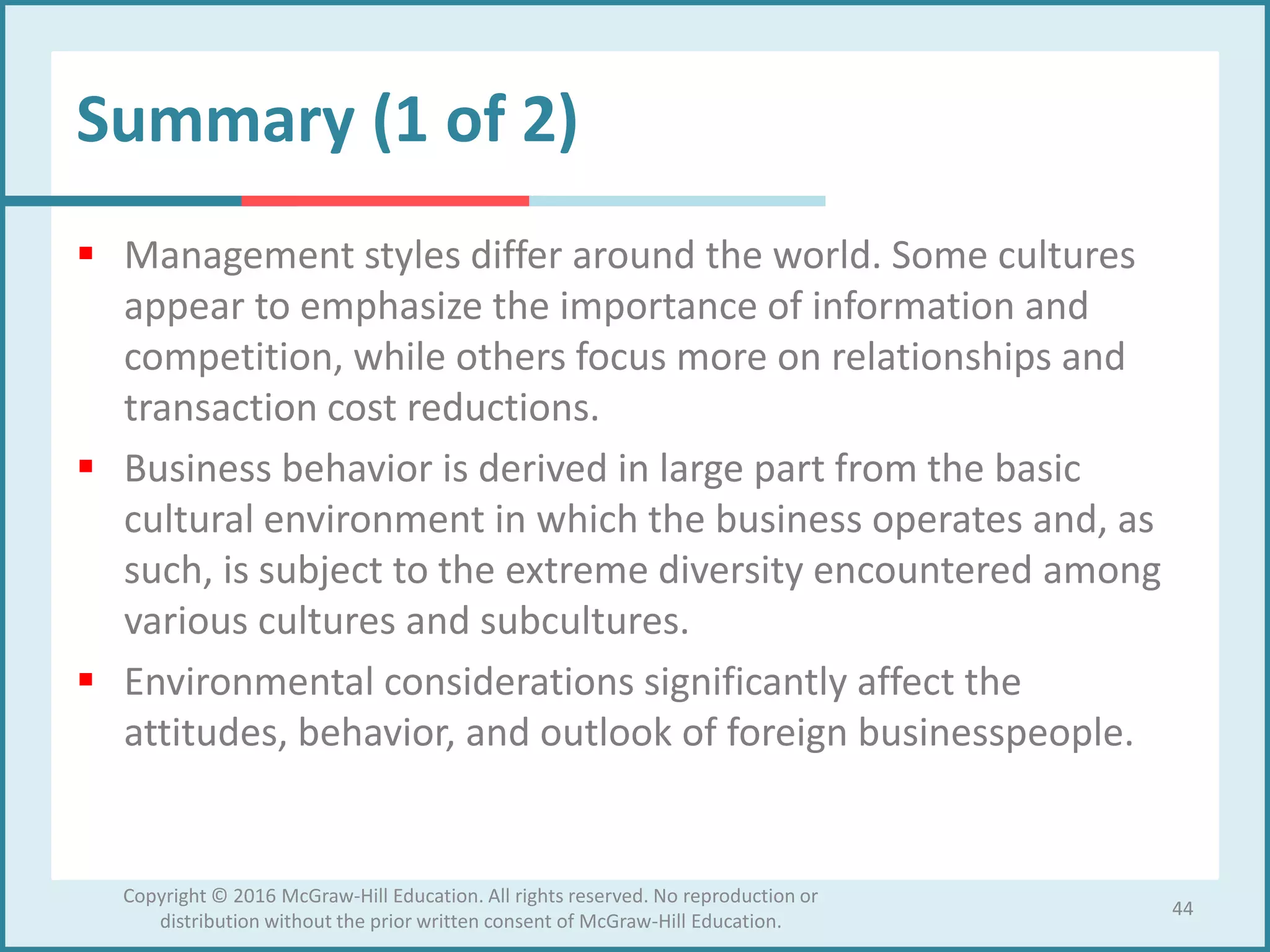

![Source: Robert Levine,

“The Pace of Life in 31

Countries,” American

Demographics,

November 1997.

Reprinted with

permission of Robert

Levine.

Overall

Pace

Country Walking 60

Feet

Postal

Service

Public

Clocks

12 Poland 12 15 8

13 Costa Rica 16 10 15

14 Taiwan 18 7 21

15 Singapore 25 11 4

16 United

States

6 23 20

17 Canada 11 21 22

18 South Korea 20 20 16

19 Hungary 19 19 18

20 Czech

Republic

21 17 23

21 Greece 14 13 29

Exhibit 5.3

(2 of 3)

Speed Is

Relative

Rank of 31 countries for overall pace of life [combination of three measures: (1) minutes

downtown pedestrians take to walk 60 feet, (2) minutes it takes a postal clerk to

complete a stamp-purchase transaction, and (3) accuracy in minutes of public clocks].

21

Copyright © 2016 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or

distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill Education.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pptch05kp-170221211928/75/Chapter-5-PowerPoint-21-2048.jpg)

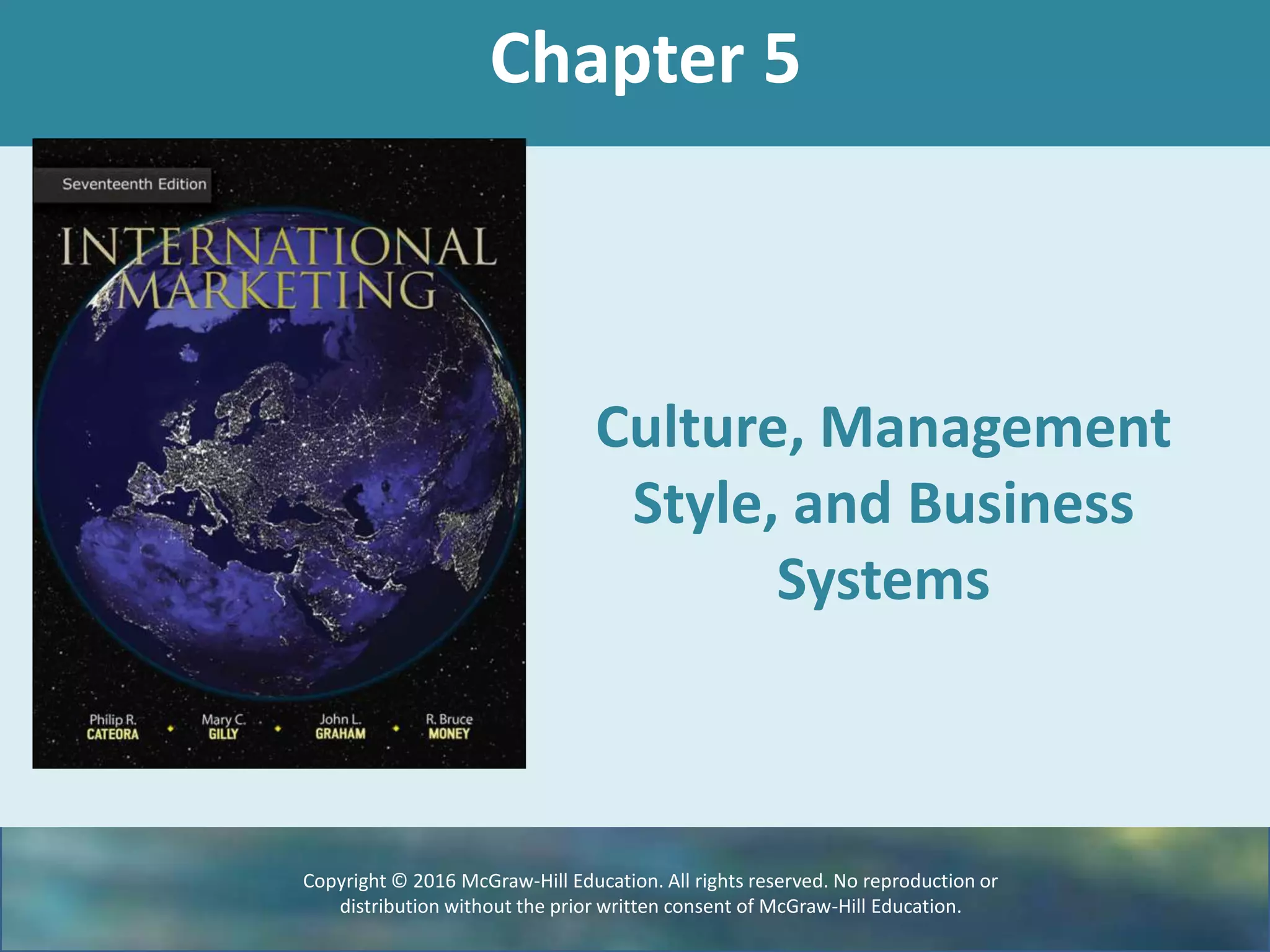

![Source: Robert Levine,

“The Pace of Life in 31

Countries,” American

Demographics, November

1997. Reprinted with

permission of Robert

Levine.

Overall

Pace

Country Walking 60

Feet

Postal

Service

Public

Clocks

22 Kenya 9 30 24

23 China 24 25 12

24 Bulgaria 27 22 17

25 Romania 30 29 5

26 Jordan 28 27 19

27 Syria 29 28 27

28 El

Salvador

22 16 31

29 Brazil 31 24 28

30 Indonesia 26 26 30

31 Mexico 17 31 26

Exhibit 5.3

(3 of 3)

Speed Is

Relative

Rank of 31 countries for overall pace of life [combination of three measures: (1) minutes

downtown pedestrians take to walk 60 feet, (2) minutes it takes a postal clerk to

complete a stamp-purchase transaction, and (3) accuracy in minutes of public clocks].

22

Copyright © 2016 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or

distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill Education.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pptch05kp-170221211928/75/Chapter-5-PowerPoint-22-2048.jpg)