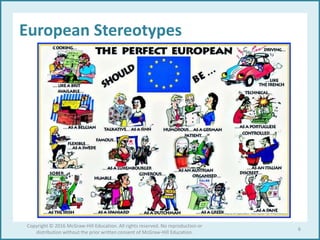

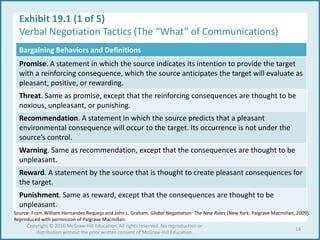

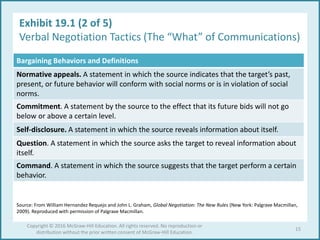

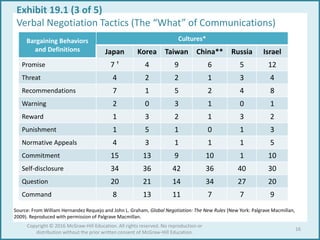

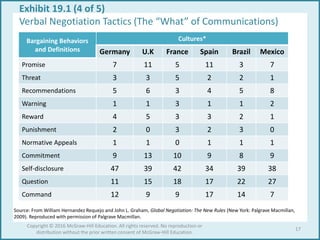

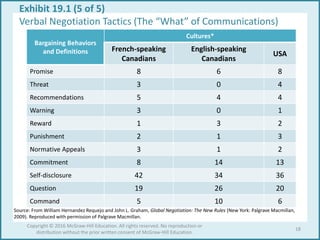

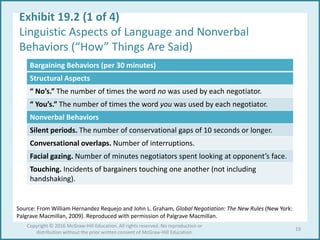

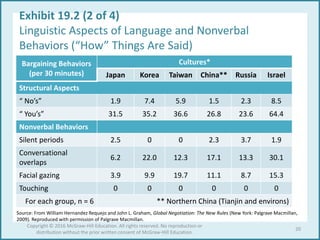

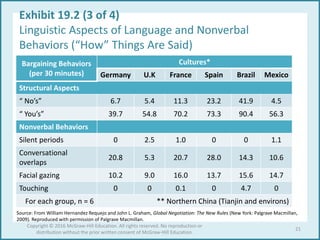

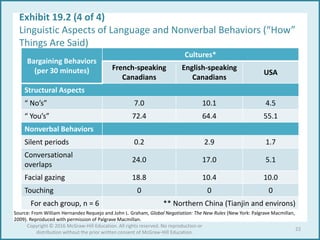

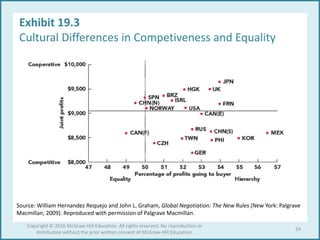

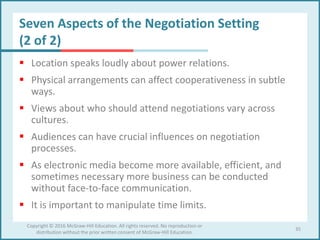

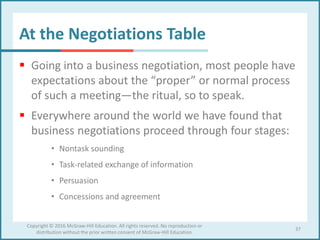

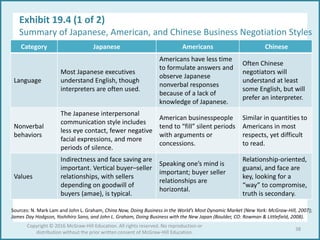

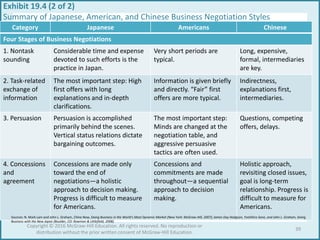

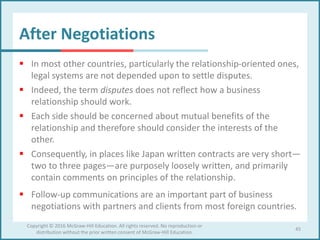

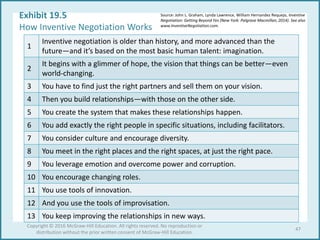

This document discusses international business negotiations. It begins by outlining the learning objectives, which focus on understanding how culture influences negotiation behaviors and styles. It then provides examples of cultural stereotypes to avoid when negotiating internationally. Several exhibits analyze data on negotiation tactics and behaviors across different cultures. Key differences are identified in areas like language use, nonverbal behaviors, and preferred communication styles. The document emphasizes that successful international negotiations require understanding both cultural and individual factors, rather than relying on stereotypes. The goal is to negotiate effectively across borders.